目次

「ルーゴン・マッカール叢書」第17巻『獣人』の概要とあらすじ

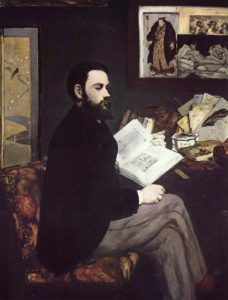

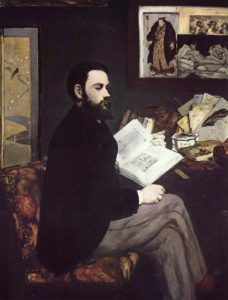

エミール・ゾラ(1840-1902) Wikipediaより

エミール・ゾラ(1840-1902) Wikipediaより

『獣人』はエミール・ゾラが24年かけて完成させた「ルーゴン・マッカール叢書」の第17巻目にあたり、1890年に出版されました。

私が読んだのは藤原書店出版の寺田光德訳の『獣人』です。

今回も帯記載のあらすじを見ていきましょう。

19世紀、時代の先頭を驀進する鉄道を駆使した“鉄道小説”の先駆!

官能の果てに愛する女を刺し殺した機関士が秘める人間の血腥い獣性を抉る。

◆鉄道によって同時代の社会と人々を活写

「叢書」中屈指の人気を誇る、探偵小説的興趣をもった作品。西部鉄道ル・アーヴル駅の助役ルボーが妻のセヴリーヌと謀って社長のグランモランを走る車中で殺害する。

主人公の機関士ジャックはその殺人を偶然目撃するが、セヴリーヌに惹かれて事件の証言を拒み、それが機縁となって彼女が今度は彼の愛人となる。

だが最後にジャックは女性に対する魅惑と恐怖の衝動に駆られて、発作的に彼女を自らの手で殺害してしまう。これがジャックを「獣人」と称させるゆえんである。

第二帝政期に鉄道は文明と進歩の象徴として時代の先頭を疾駆していた。この小説の影の主人公が鉄道であると読みとることができれば、鉄道を駆使して同時代の社会とそこに生きる人々の感性を活写し、小説に新境地を切り開いた、ゾラの斬新さが理解できる。

※一部改行しました

藤原書店出版 寺田光德訳『獣人』

今作の主人公のジャックは『居酒屋』のジェルヴェーズの次男にあたり、狂気の遺伝を持つマッカール家に位置します。

あわせて読みたい

ゾラの代表作『居酒屋』あらすじと感想~パリの労働者と酒、暴力、貧困、堕落の必然的地獄道。

『居酒屋』は私がゾラにはまるきっかけとなった作品でした。

ゾラの『居酒屋』はフランス文学界にセンセーションを起こし、この作品がきっかけでゾラは作家として確固たる地位を確立するのでありました。

ゾラ入門におすすめの作品です!

ルーゴン・マッカール家家系図

『制作』で登場した兄のクロードは芸術に対する狂気を、『ジェルミナール』で登場した弟のエチエンヌは酒を飲むと殺人衝動が起こるという狂気を持っていましたが今作の主人公ジャックも、女性に強い欲望を感じるとその女性を殺したくなるという狂気を持っています。

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『制作』あらすじと感想~天才画家の生みの苦しみと狂気!印象派を知るならこの1冊!

この物語はゾラの自伝的な小説でもあります。主人公の画家クロードと親友の小説家サンドーズの関係はまさしく印象派画家セザンヌとゾラの関係を彷彿させます。

芸術家の生みの苦しみを知れる名著です!

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『ジェルミナール』あらすじと感想~炭鉱を舞台にしたストライキと労働者の悲劇 ゾラの描く蟹工船

『ジェルミナール』では虐げられる労働者と、得体の知れない株式支配の実態、そして暴走していく社会主義思想の成れの果てが描かれています。

社会主義思想と聞くとややこしそうな感じはしますが、この作品は哲学書でも専門書でもありません。ゾラは人々の物語を通してその実際の内容を語るので非常にわかりやすく社会主義思想をストーリーに織り込んでいます。

その狂気を抑えるために彼は日々苦しめられ、それを忘れることができるのは鉄道員として列車を動かしている時だけでした。

こうした体の奥底から湧き上がる制御不能の殺人衝動を持った人間の心理的葛藤、そして殺人事件へと巻き込まれていく過程を描いたのが今作の『獣人』という物語になります。

感想―ドストエフスキー的見地から

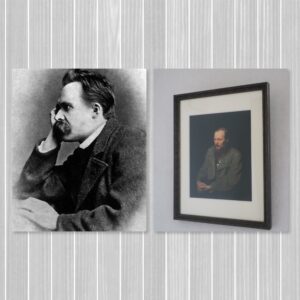

実は、『獣人』はドストエフスキーと重大な関わりがある作品となっています。

なんと、ゾラは『罪と罰』にインスパイアされてこの作品を書き上げたと言われているのです。

あわせて読みたい

ドストエフスキーの代表作『罪と罰』あらすじと感想~ドストエフスキーの黒魔術を体感するならこの作品

ドストエフスキーがこの小説を書き上げた時「まるで熱病のようなものに焼かれながら」精神的にも肉体的にも極限状態で朝から晩まで部屋に閉じこもって執筆していたそうです。

もはや狂気の領域。

そんな怪物ドストエフスキーが一気に書き上げたこの作品は黒魔術的な魔力を持っています。

百聞は一見に如かずです。騙されたと思ってまずは読んでみてください。それだけの価値があります。黒魔術の意味もきっとわかると思います。これはなかなかない読書体験になると思います。

訳者解説を見ていきましょう。

殺人について考察をしている同時代の有名な小説を挙げるとすれば、なんと言ってもドストエフスキーの『罪と罰』であろう。

そこでは主人公ラスコーリニコフが、エリートには殺人が許されるとして金貸し老婆殺害を敢行していた。『罪と罰』仏語版は一八八五年に出版され、ゾラもこれを読み『獣人』の「章案」のなかで二度ほどこれに言及している。

なるほど『獣人』の主人公ジャックはルボーを殺そうとたくらむ際に、ラスコーリニコフと同じように強者には邪魔者を殺す権利があるというような理屈を繰り出すのだが、それでも最後までどうしてもそのような納得ずくでの殺人、いわゆる理性的な殺人は敢行できなかった。しかし理性的な殺人をルボーに対して行えなかった代わりに、恋人のセヴリーヌは発作的に殺してしまう。

※一部改行しました

藤原書店出版 寺田光德訳『獣人』P517

『罪と罰』ではラスコーリニコフは理性の極限まで突き進み、その結果殺人を犯すことになりました。

ドストエフスキーは理性の行きつく果てが殺人であると『罪と罰』で描いたのですが、ゾラはそれに正反対の意見をこの小説で提出することになります。

小説本編からまさにそれが端的に示されているところを引用します。ジャックが愛人セヴリーヌの夫ルボーを殺そうか悩んでいるシーンです。

ルボーは自分の幸福を妨げている唯一の障害ではなかろうか?彼が死んだら、愛するセヴリーヌと結婚し、もうこそこそしないで、彼女のすべてを永遠に自分のものにできる。それから金が、財産が手にはいる。今のきつい仕事はやめて、アメリカに行って今度は社長だ。アメリカでは機関士たちがシャべルで黄金をざくざく掘り出していると同僚たちがよく話していた。アメリカでの新生活が夢のように眼の前に繰り出されてきた。情熱的に愛してくれる妻と、たちまち手にはいる巨万の富、安楽な生活、満々たる野心、なんでも思いのままだ。この夢を実現するには、ちょっと行動するだけ、人ひとり殺害するだけでいい。あいつは歩くのを邪魔する雑草のような男だから、踏みつぶしてやろう。あいつはつまらんやつで、近頃脂肪がついて動きが鈍く、賭事にばかげた情熱を燃やし、以前のエネルギーをすっかり失ってしまった。どうしてあんなやつを許しておけよう?どこを見てもあいつには同情の余地がまったくない。あいつはすべての点で有罪だ。どう考えてみても、あいつが死ねばみんなのためになるとしか思えない。殺すのをためらうほうがどうかしてるし、卑怯と言うべきだ。(中略)

あいつを殺そう、決めた。それで病気から回復するし、愛する妻も、財産も手にすることができるのだから。だれかを殺す必要があるとすれば、それはあいつだ。すくなくとも、利害からしても論理的に考えても、きちんと理由をつけて殺せるのだから。(中略)

しかし彼がまったく細々としたことにこだわっているあいだに、どうしようもない嫌悪感がひそかに戻ってきた。内心の抗議の声で彼はまたすっかり起き上がった。いや、いや、殺してはいけない!またもや殺すことは残虐な、実行不可能な、考えられないことのように思えてきた。彼の心中では文明人が反抗していた。それは教育によって育くまれた力であり、代々伝えられてきた思想で、ゆっくりと揺るぎなく築き上げられた人間の基礎であった。人殺しはすべきでない、何世代にもわたるその思想を彼は乳といっしょに吸収してきた。彼の脳髄は文明で洗練され、良心を詰め込まれ、彼が殺人について理屈を考え始めるやいなや、それを恐怖で押しのけた。そうだ、本能的な欲求や興奮に襲われたときなら人殺しはできる!だが打算から、利害から、意図的に人殺しをしようとしても、絶対に自分にはできないだろう!(中略)

いや、いや、人殺しはできない!こんな無防備な男を殺すなんて。理性ではけっして殺人はやれない。食いつこうとする本能が、獲物に飛びかかろうとする体の躍動が、獲物を引き裂とうとする熱狂が是非とも必要だ。

藤原書店出版 寺田光德訳『獣人』P366-376

どうでしょうか。『罪と罰』のラスコーリニコフと比べてみてください。

ものの見事にラスコーリニコフとジャックが真逆のことを言っているのがわかるかと思います。(ラスコーリニコフの思想については以下の記事を参照ください)

あわせて読みたい

やはり『罪と罰』は面白い…!ナポレオンという切り口からその魅力を考える

私がドストエフスキーにおいて「面白い」という言葉を使う時は、アハハと笑うような「面白い」でもなく、あ~楽しかったいう「面白い」とも、スカッとするエンタメを見るような「面白い」とも違います。

時間を忘れてのめり込んでしまうような、それでいてなおかつ、読んだ後もずっと心にこびりつくような、そういう読後感があるような面白さを言います。

『罪と罰』にはそのような面白さをもたらしてくれる思想的な奥行きがこれでもかと描かれています。

そのひとつがラスコーリニコフの言うナポレオン思想です。

ドストエフスキーは理性こそ人間を破滅に追いやると主張し、ゾラは人間の獣性、つまり本能こそ殺人へと導くと言うのです。

ジャックは最後まで理性で殺人を犯すことができず、その代わりにあっさりと衝動によってセヴリーヌを殺してしまうのです。

あまりにあっさりとです。

散々ルボーを殺そうか殺すまいかと頭で悩んでいたのに、愛するセヴリーヌに対しては彼は驚くほどあっさりと手を下してしまうのです。(※もちろん、それまで彼女を殺すまいと我慢はしていたのですが)

理性で殺したラスコーリニコフ、本能で殺したジャック。

この二人の対比はドストエフスキーとゾラの人間観の違いを最も明確に示しているのではないでしょうか。

これ以上深くはここでは立ち入りませんが、『獣人』は『罪と罰』との比較という意味では非常に興味深い作品となっています。

『罪と罰』にはまった人ならぜひともこちらの作品も読んで頂けたらなと思います。

バルザックの『ゴリオ爺さん』(以下の記事参照)と共におすすめしたい一冊です。

あわせて読みたい

バルザック『ゴリオ爺さん』あらすじと感想―フランス青年の成り上がり物語~ドストエフスキー『罪と罰』...

この小説を読んで、私は驚きました。

というのも、主人公の青年ラスティニャックの置かれた状況が『罪と罰』の主人公ラスコーリニコフとそっくりだったのです。

『ゴリオ爺さん』を読むことで、ドストエフスキーがなぜラスティニャックと似ながらもその進む道が全く異なるラスコーリニコフを生み出したのかということも考えることが出来ました。

以上、「ゾラ『獣人』殺人は理性か本能か!『罪と罰』にインスパイアされたゾラの鉄道サスペンス」でした。

Amazon商品ページはこちら↓

獣人 ゾラセレクション(6)

次の記事はこちら

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『金』あらすじと感想~19世紀パリで繰り広げられたロスチャイルドVSパリ新興銀行の金融戦争!

『獲物の分け前』で主に土地投機によって巨額の金を稼いだ主人公のサッカールでしたが、今作では巨大銀行を設立することで新たな戦いに身を投じていく様子が描かれています。サッカールのライバルのユダヤ人はあのロスチャイルド家がモデルになっています。フランス第二帝政期では実際に新興銀行とロスチャイルド銀行との金融戦争が勃発していました。ゾラはこうした事実を丹念に取材し、この作品に落とし込んでいます。

前の記事はこちら

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『夢想』あらすじと感想~ゾラの描くファンタスティックな夢想と少女の恋。ゾラらしからぬ作風に驚...

正直に申しまして、この作品は「ルーゴン=マッカール叢書」20巻中、読んでいて最も困惑する作品でした。

と、言いますのも、アンジェリックの夢想があまりにエキセントリックであり、しかもその夢想に沿う形で本当に王子様が現れて恋に落ち、さらにさらに王子様が駆け落ちまで申し込んでくるという、ゾラらしからぬファンタジー要素があまりに多い筋書きだったからなのです。

私にとってよくも悪くもこの作品は不思議なインパクトを与える作品でした。

関連記事

あわせて読みたい

尾﨑和郎『ゾラ 人と思想73』あらすじと感想~ゾラの生涯や特徴、ドレフュス事件についても知れるおすす...

文学史上、ゾラほど現代社会の仕組みを冷静に描き出した人物はいないのではないかと私は思っています。

この伝記はそんなゾラの生涯と特徴をわかりやすく解説してくれる素晴らしい一冊です。ゾラファンとしてこの本は強く強く推したいです。ゾラファンにとっても大きな意味のある本ですし、ゾラのことを知らない方にもぜひこの本はおすすめしたいです。こんな人がいたんだときっと驚くと思います。そしてゾラの作品を読みたくなることでしょう。

あわせて読みたい

(8)パリのゾラ『ルーゴン・マッカール叢書』ゆかりの地を一挙紹介~フランス第二帝政のパリが舞台

今回の記事では私が尊敬する作家エミール・ゾラの代表作『ルーゴン・マッカール叢書』ゆかりの地を紹介していきます。

『ルーゴン・マッカール叢書』はとにかく面白いです。そしてこの作品群ほど私たちの生きる現代社会の仕組みを暴き出したものはないのではないかと私は思います。

ぜひエミール・ゾラという天才の傑作を一冊でもいいのでまずは手に取ってみてはいかがでしょうか。そしてその強烈な一撃にぜひショックを受けてみて下さい。

あわせて読みたい

本当にいい本とは何かー時代を経ても生き残る名作が古典になる~愛すべきチェーホフ・ゾラ

チェーホフもゾラも百年以上も前の作家です。現代人からすれば古くさくて小難しい古典の範疇に入ってしまうかもしれません。

ですが私は言いたい!古典と言ってしまうから敷居が高くなってしまうのです!

古典だからすごいのではないのです。名作だから古典になったのです。

チェーホフもゾラも、今も通ずる最高の作家です!

あわせて読みたい

フランス人作家エミール・ゾラとドストエフスキー ゾラを知ればドストエフスキーも知れる!

フランス第二帝政期は私たちの生活と直結する非常に重要な時代です。

そしてドストエフスキーはそのようなフランスに対して、色々と物申していたのでありました。

となるとやはりこの時代のフランスの社会情勢、思想、文化を知ることはドストエフスキーのことをより深く知るためにも非常に重要であると思いました。

第二帝政期のフランスをさらに深く知るには何を読めばいいだろうか…

そう考えていた時に私が出会ったのがフランスの偉大なる作家エミール・ゾラだったのです。

あわせて読みたい

『居酒屋』の衝撃!フランス人作家エミール・ゾラが面白すぎた件について

ゾラを知ることはそのままフランス社会を学ぶことになり、結果的にドストエフスキーのヨーロッパ観を知ることになると感じた私は、まずゾラの代表作『居酒屋』を読んでみることにしました。

そしてこの小説を読み始めて私はとてつもない衝撃を受けることになります。

あわせて読みたい

「ルーゴン・マッカール叢書」一覧~代表作『居酒屋』『ナナ』を含むゾラ渾身の作品群

これまで20巻にわたり「ルーゴン・マッカール叢書」をご紹介してきましたが、この記事ではそれらを一覧にし、それぞれの作品がどのような物語かをざっくりとまとめていきます。

あわせて読みたい

僧侶が選ぶ!エミール・ゾラおすすめ作品7選!煩悩満載の刺激的な人間ドラマをあなたに

世の中の仕組みを知るにはゾラの作品は最高の教科書です。

この社会はどうやって成り立っているのか。人間はなぜ争うのか。人間はなぜ欲望に抗えないのか。他人の欲望をうまく利用する人間はどんな手を使うのかなどなど、挙げようと思えばきりがないほど、ゾラはたくさんのことを教えてくれます。

そして何より、とにかく面白い!私はこれまでたくさんの作家の作品を読んできましたが、ゾラはその中でも特におすすめしたい作家です!

あわせて読みたい

19世紀後半のフランス社会と文化を知るならゾラがおすすめ!エミール・ゾラ「ルーゴン・マッカール叢...

前回の記事「エミール・ゾラが想像をはるかに超えて面白かった件について―『居酒屋』の衝撃」ではエミール・ゾラの「ルーゴン・マッカール叢書」なるものがフランス第二帝政のことを学ぶにはもってこいであり、ドストエフスキーを知るためにも大きな意味があるのではないかということをお話ししました。

この記事ではその「ルーゴン・マッカール叢書」とは一体何なのかということをざっくりとお話ししていきます。

あわせて読みたい

木村泰司『印象派という革命』あらすじと感想~ゾラとフランス印象派―セザンヌ、マネ、モネとの関係

前回までの記事では「日本ではなぜゾラはマイナーで、ドストエフスキーは人気なのか」を様々な面から考えてみましたが、今回はちょっと視点を変えてゾラとフランス印象派絵画についてお話ししていきます。

私はゾラに興味を持ったことで印象派絵画に興味を持つことになりました。

それとは逆に、印象派絵画に興味を持っている方がゾラの小説につながっていくということもあるかもしれません。ぜひともおすすめしたい記事です

あわせて読みたい

エミール・ゾラの小説スタイル・自然主義文学とは~ゾラの何がすごいのかを考える

ある作家がどのようなグループに属しているのか、どのような傾向を持っているのかということを知るには〇〇主義、~~派という言葉がよく用いられます。

ですが、いかんせんこの言葉自体が難しくて余計ややこしくなるということがあったりはしませんでしょうか。

そんな中、ゾラは自分自身の言葉で自らの小説スタイルである「自然主義文学」を解説しています。それが非常にわかりやすかったのでこの記事ではゾラの言葉を参考にゾラの小説スタイルの特徴を考えていきます。

あわせて読みたい

日本ではなぜゾラはマイナーで、ドストエフスキーは人気なのか―ゾラへの誤解

前回の記事ではフランスでの発行部数からゾラの人気ぶりを見ていきました。

その圧倒的な売れ行きからわかるように、ゾラはフランスを代表する作家です。

ですが日本で親しまれている大作家が数多くいる中で、ゾラは日本では異様なほど影が薄い存在となっています。

なぜゾラはこんなにも知名度が低い作家となってしまったのでしょうか。

今回の記事では日本でゾラがマイナーとなってしまった理由と、それと比較するためにドストエフスキーがなぜ日本で絶大な人気を誇るのかを考えていきたいと思います。

あわせて読みたい

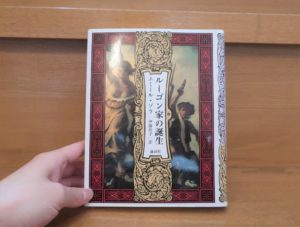

ゾラ『ルーゴン家の誕生』あらすじと感想~衝撃の面白さ!ナポレオン第二帝政の始まりを活写する名作!...

この本はゾラの作品中特におすすめしたい名作中の名作です!

読んでいて「あぁ~さすがですゾラ先生!」と 何度心の中で うめいたことか!もう言葉のチョイス、文章のリズム、絶妙な位置で入る五感に働きかける表現、ゾラ節全開の作品です。正直、私は『居酒屋』や『ナナ』よりもこの作品の方が好きです。とても面白かったです。

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『パリの胃袋』あらすじと感想~まるで仏教書!全てを貪り食うパリの飽くなき欲望!食欲は罪か、そ...

私は『ルーゴン・マッカール叢書』でどの作品が1番好きかと言われたらおそらくこの『パリの胃袋』を挙げるでしょう。それほど見事に人間の欲望を描いています。

ゾラ得意の映画的手法や、匂いなどの五感を刺激する描写、欲望をものや動物を描くことで比喩的に表現する手腕など、すばらしい点を列挙していくときりがないほどです。

あわせて読みたい

ゾラの代表作『居酒屋』あらすじと感想~パリの労働者と酒、暴力、貧困、堕落の必然的地獄道。

『居酒屋』は私がゾラにはまるきっかけとなった作品でした。

ゾラの『居酒屋』はフランス文学界にセンセーションを起こし、この作品がきっかけでゾラは作家として確固たる地位を確立するのでありました。

ゾラ入門におすすめの作品です!

あわせて読みたい

ゾラの代表作『ナナ』あらすじと感想~舞台女優の華やかな世界の裏側と上流階級の実態を暴露!

ゾラの代表作『ナナ』。フランス帝政の腐敗ぶり、当時の演劇界やメディア業界の舞台裏、娼婦たちの生活など華やかで淫蕩に満ちた世界をゾラはこの小説で描いています。

欲望を「食べ物」に絶妙に象徴して描いた作品が『パリの胃袋』であるとするならば、『ナナ』はど直球で性的な欲望を描いた作品と言うことができるでしょう。

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『ごった煮』あらすじと感想~ブルジョワの偽善を暴く痛快作!貴婦人ぶっても一皮むけば…

この作品は『ボヌール・デ・ダム百貨店』の物語が始まる前の前史を描いています。

主人公のオクターヴ・ムーレは美男子で女性にモテるプレイボーイです。そして彼がやってきたアパートでは多くのブルジョワが住んでいてその奥様方と関係を持ち始めます。

そうした女性関係を通してオクターヴは女性を学び、大型商店を営むというかねてからの野望に突き進もうとしていきます。

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『ボヌール・デ・ダム百貨店』あらすじと感想~欲望と大量消費社会の秘密~デパートの起源を知るた...

この作品はフランス文学者鹿島茂氏の『 デパートを発明した夫婦』 で参考にされている物語です。

ゾラは現場での取材を重要視した作家で、この小説の執筆に際しても実際にボン・マルシェやルーブルなどのデパートに出掛け長期取材をしていたそうです。

この本を読むことは私たちが生きる現代社会の成り立ちを知る手助けになります。

もはや街の顔であり、私たちが日常的にお世話になっているデパートや大型ショッピングセンターの起源がここにあります。

非常におすすめな作品です。

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『ジェルミナール』あらすじと感想~炭鉱を舞台にしたストライキと労働者の悲劇 ゾラの描く蟹工船

『ジェルミナール』では虐げられる労働者と、得体の知れない株式支配の実態、そして暴走していく社会主義思想の成れの果てが描かれています。

社会主義思想と聞くとややこしそうな感じはしますが、この作品は哲学書でも専門書でもありません。ゾラは人々の物語を通してその実際の内容を語るので非常にわかりやすく社会主義思想をストーリーに織り込んでいます。

あわせて読みたい

ゾラ『制作』あらすじと感想~天才画家の生みの苦しみと狂気!印象派を知るならこの1冊!

この物語はゾラの自伝的な小説でもあります。主人公の画家クロードと親友の小説家サンドーズの関係はまさしく印象派画家セザンヌとゾラの関係を彷彿させます。

芸術家の生みの苦しみを知れる名著です!

あわせて読みたい

ニーチェ発狂の現場と『罪と罰』ラスコーリニコフの夢との驚くべき酷似とは

1889年1月、ニーチェ45歳の年、彼は発狂します。彼が発狂したというエピソードは有名ですがその詳細に関しては私もほとんど知りませんでした。

しかし、参考書を読み私は衝撃を受けました。その発狂の瞬間がドストエフスキーの代表作『罪と罰』の主人公ラスコーリニコフが見た夢とそっくりだったのです。

コメント