『カラマーゾフの兄弟』はなぜ難しい?何をテーマに書かれ、どのような背景で書かれたのか~ドストエフスキーがこの小説で伝えたかったこととは

『カラマーゾフの兄弟』はなぜ難しい?何をテーマに書かれ、どのような背景で書かれたのか~ドストエフスキーがこの小説で伝えたかったこととは

※この記事は前回の記事とひとつながりのものとして書きました。ですのでシンプルに「なぜ『カラマーゾフの兄弟』は難しいのかということを知りたい方は目次の「おわりに~なぜ『カラマーゾフの兄弟』は難しい?」をご覧ください。

前回の記事「『カラマーゾフの兄弟』は本当に父殺しの小説なのだろうか本気で考えてみた~フロイト『ドストエフスキーの父親殺し』を読む」ではフロイトの『ドストエフスキーと父親殺し』を参考に、いかにしてフロイトが父親殺しの理論をドストエフスキーに適用し、解釈していったことを見ていきました。

フロイトは『カラマーゾフの兄弟』を父親殺しの小説であり、ドストエフスキーはエディプス・コンプレックスの典型的な例であると断言するのですが、前回のページでひとつひとつ検証した結果、それは誤りであることが明らかになりました。

フロイトが『カラマーゾフの兄弟』を「父親殺し」をテーマに読むのは自由です。そしてそこから自由に想像して物語を語るのも自由です。

ですが、フロイトは自説の「父殺し」という観点のみでドストエフスキーを解釈し、ドストエフスキーに関する事実関係や小説を書くに至る流れ、思想を無視しています。無視するだけならまだしも、事実ではないことを事実と断言し自説の補強のために用いています。(例えば、「ドストエフスキーは少女を強姦をした。ドストエフスキーは自身の体験を小説に書いている」など。詳しくは前回のページをご覧ください)

そして父親殺しを前提条件とした彼のドストエフスキー論はどんどん飛躍していきます。

「フロイトの『レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチの幼年期の想い出』に見るフロイト理論の仕組みとその問題点とは」の記事で述べましたようにフロイトは基本的に逆ピラミッド型でその解釈を広げていきます。ダ・ヴィンチにおいてもメモに書かれていた「禿げ鷹」というたった一つの言葉からエジプトの女神やルター派神父によるマリア伝説までその想像を膨らませています。

つまり、連想できるものはどこまでも飛躍することができるのです。フロイトは父親をツァー(ロシア皇帝)とキリストに拡大していきます。そしてエディプス・コンプレックスによると当然ながらツァーもキリストも倒さなければならない(殺したい)存在として扱われることになります。

そうなると王政打破を狙う革命家、イエスに反発する無神論者ドストエフスキーという解釈も可能になります。

もちろん、どちらも根拠はありません。

フロイトは多くの出来事や証言を自説の根拠であると断言して持ち出しますが、その根拠はこれまで当ブログで見てきた通り否定されています。

ですがフロイトは「これは事実である」と断言します。断言に断言を重ね、一見筋が通った見事な物語を展開し、私たちを圧倒します。

ですが、その実態は、推測に推測、解釈に解釈のフロイトの創作物語なのでした。

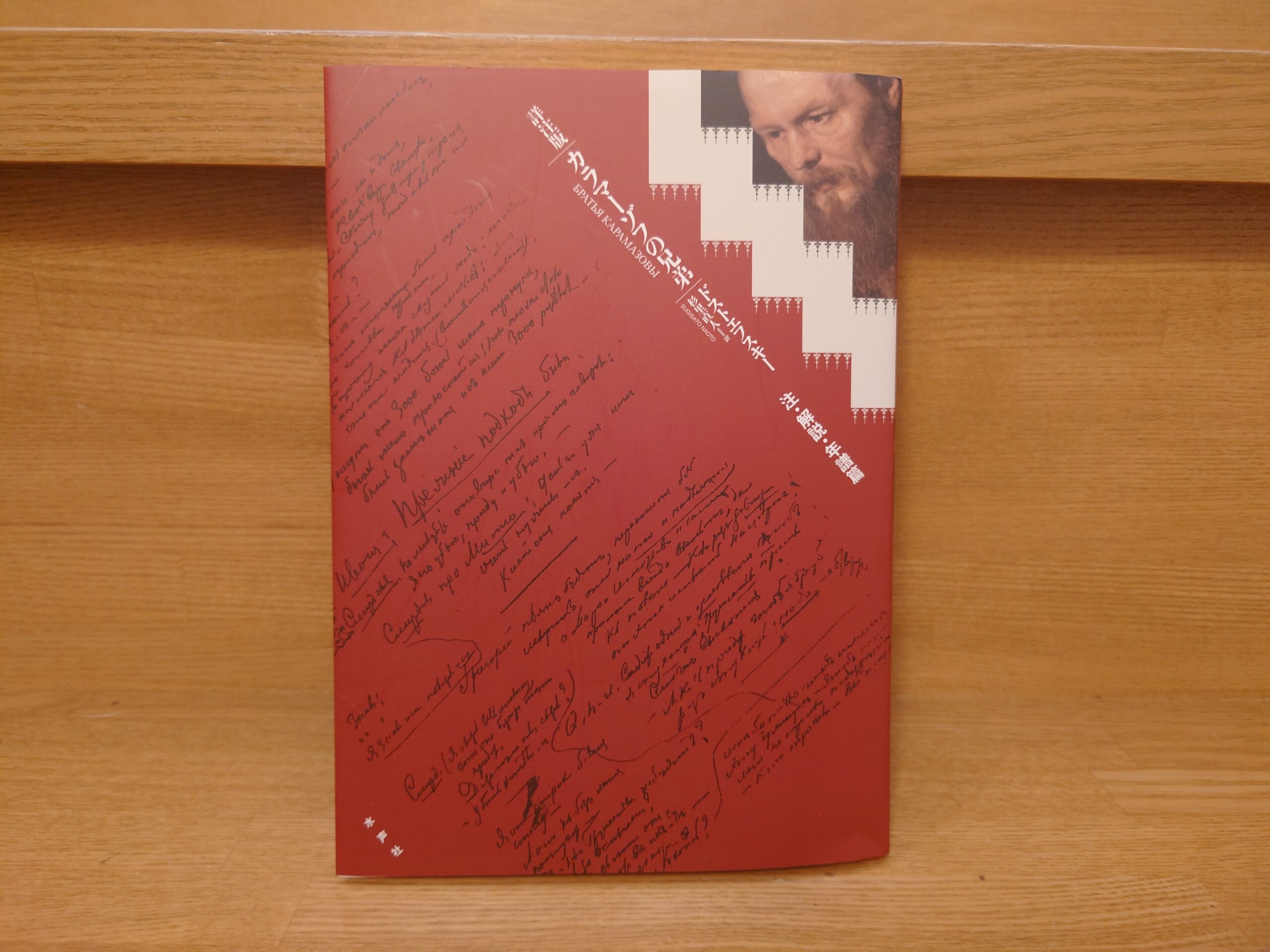

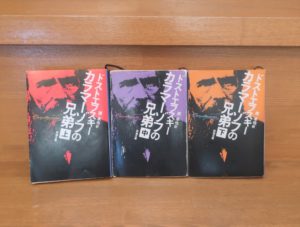

こうした流れを前回までのページでお話ししてきたのでありますが、今回の記事では実際にその『カラマーゾフの兄弟』が書かれた背景とはどのようなものだったのかをお話していきます。フロイトは「父殺し理論」ですべて片付けてしまいましたが、実際のところは何を主題に書こうとしていたのでしょうか。杉里直人氏の 『【詳注版】カラマーゾフの兄弟【注・解説・年譜編】』 ではそのことについて非常にわかりやすく解説されていましたので今回はそちらを参考にお話ししていきます。

杉里直人 『【詳注版】カラマーゾフの兄弟【注・解説・年譜編】』

まず、今回参考にする参考書についてお話ししていきます。

信仰と死、家族関係、殺人ミステリー、生への絶望と希望…

ロシア本国での最新の研究成果を反映し、かつ歴代の日・英・仏・独の翻訳をつぶさに検討しながら作りあげられた、本邦16番目となる新訳の、すべてを1冊に収めた本篇と、見落とされて来た聖書テクストへの密かな言及、ドストエフスキーの他の作品との相互参照、物語の核心部に関連する当時の裁判・教育制度の解説、非ロシア人には分かりにくい諺、衣服、風俗の説明等の膨大な注釈を含む、注・解説・年譜篇からなる豪華二巻本。わが国における本作品の翻訳の長い歴史に、新たな局面を切り開く決定版。【訳者について】

blog水声社、商品ページより

杉里直人(すぎさとなおと)

1956年、岐阜県に生まれる。早稲田大学文学研究科博士後期課程満期退学。現在、早稲田大学、明治大学、東京理科大学非常勤講師。専門は十九世紀ロシア文学・文学理論。主な著書に、『論集 ドストエフスキーと現代』(共著、多賀出版、2001年)、『ロシアフォークロアの世界』(共著、群像社、2005年)などが、主な訳書に、ニコライ・カレートニコフ『モスクワの前衛音楽家』(新評論、1996年)、ミハイル・バフチン『フランソワ・ラブレーの作品と中世・ルネサンスの民衆文化』(『ミハイル・バフチン全著作』第7巻、水声社、2007年)などがある。

この本はロシア文学研究者の杉里直人氏がロシアでの最新の研究をふまえて書かれた『カラマーゾフの兄弟』の新訳です。そしてこの本でありがたいのは非常に詳しい「注・解説」が書かれた本もセットになっている点です。

今回はこの『注・解説・年譜篇』を参考にカラマーゾフ成立の過程とドストエフスキーがこの小説で何を書こうとしていたかを見ていきたいと思います。

『カラマーゾフの兄弟』の萌芽1~長編小説のプラン「無神論」と「大罪人の生涯」

ドストエフスキーが新しい小説について初めて公言するのは、『作家の日記』一八七七年十二月号第二章第五節「読者諸兄に」においてである。そこで二年間にわたった『作家の日記』の刊行をいったん終え、翌年は「『日記』を刊行していたこの二年間の間に、それと気づかないうちにおのずと私の中でできあがっていた、ある芸術的労作に実際、取り組む」(ПCC,26.・126)つもりだと読者に告げる。

もっとも、『カラマーゾフ』に結実する構想の最初の萌芽が見られるのは、その十年ほど前である。

一八六八年十二月、妻アンナ・グリゴーリエヴナとともにヨーロッパを旅行中だったドストエフスキーは詩人アポロン・マイコフ宛の手紙で「無神論」と題する大長編のプランを語る。

それによると、主人公はそれなりの官等にあるロシア人で、それまで軌道をはずれることなかつたのに、四十五歳になって突然、神への信仰を喪失し、無神論者、スラヴ派、西欧派、聖人、イエズス会士、鞭身派などを遍歴したあげく、「最後にはキリストとロシアの大地、ロシアのキリストとロシアの神を獲得する」(ПCC,28 KH.2・329)というものだった。

翌六九年一月のC・И・イワノワ宛の手紙では、「無神論」によって「芸術的・詩的イデーの総合を達成し」、「死ぬ前にできるだけ完全に何かで自分の意見を述べつくしたい」(ПCC,29 KH.1・24)と、この作品にかける並々ならぬ決意を語っている。

「無神論」は六九年十二月に「大罪人の生涯」と題名を変え、ドストエフスキーは翌年五月にかけてかなり詳細な創作ノートを取っている。

このノートには、諸事件の錯綜した展開、小さな挿話、主人公の細部の造形はもちろん、副人物・端役の肉づけ、会話や台詞の断片が具体的に書きこまれ、一年ほどの間に構想は急速に拡大・深化した。

一八七〇年三月のマイコフ宛手紙によると、これは五つの中編からなる、トルストイ『戦争と平和』くらいの規模の大長編になるはずで、主題は作家自身が「一生苦しんできた神の存在」で、主人公は信仰と不信仰の間を激しく揺れ動く(ПCC,29 KH.1・117)とのことだった。

第一話は一八四〇年代、主人公の幼年時代で、刑事犯罪が描かれる。

第二話は主教チーホン・ザドンスキーの修道院が舞台で、犯罪に関与した十三歳の少年がチーホンのもとに預けられ、主教との交流を通して、「全世界に勝ちたければ、おのれに勝て」との教訓を受ける。

第三話は主人公の青年時代で、実証主義と無神論に惹かれ、傲慢と人間蔑視の罪におちいり、高利貸しから蓄財の考えを吹きこまれる。偉業と悪行のコントラストは明白で、大罪人の犯罪は頂点に達する。

第四話で、主人公の精神的危機が深まり、スヒマ修道士となって、ロシア各地へ巡礼の旅に出る。思いがけない転機、恋をへて、謙虚さへの渇望に襲われる。

第五話で罪人は完全に復活し、万人に慈悲深い柔和な人間となり、最後に養育院を建てて慈善家になったのち、みずからの犯罪を告白して死んでいく(ПCC,9・125-139を参照、この部分の記述はグロスマンにもとづく)。

このメモの重要性は二点ある。

一つは第二話に登場する主教チーホン・ザドンスキーに関わる。これは《忍従・柔和・愛》を説いた十八世紀に実在の同名の聖人をモデルにしており(作家はチーホンを始め、正教の修道土や説教師の著作を数多く読んでいる)、それが発展して『悪霊』のチーホン、『カラマーゾフ』のゾシマが誕生した。

もう一点は、作者の死によって陽の目を見ることのなかった『カラマーゾフ』第二部の筋書きがこの「大罪人の生涯」と密接なつながりがあると見なされているからである。

水声社、杉里直人 『【詳注版】カラマーゾフの兄弟【注・解説・年譜編】』P205-6

※一部改行しました

前回の記事でもお話ししましたが、ルイス・ブレーガーによる伝記『フロイト 視野の暗点』によると、フロイトは無神論者で宗教に対して激しい批判を加えていました。そして彼はオーストリアを拠点としていましたのでロシアのことはほとんど知りません。彼が知るキリスト教はカトリックとプロテスタントです。

ロシアのキリスト教は同じキリスト教といってもロシア正教というカトリックやプロテスタントとはかなり異なる文化を持った宗教です。

ドストエフスキー自身もロシア正教の立場からカトリックを批判したりもしています。

ロシアの専門家ではないフロイトはロシアの歴史や文化、宗教には詳しくありません。ドストエフスキーがどのような時代背景で育ったかも、彼が読んだ偏った資料の範囲でしか知りません。さらに言えばただでさえ強固な無神論者を任ずるフロイトが、ロシア正教の教えや思想を理解していたかは疑問です。

そしてドストエフスキーがどういう思想的な流れを通って『カラマーゾフの兄弟』を執筆したかもフロイトは知りません。フロイトは自分に都合のよい情報しか得ようとしません。フロイトは自らの理論を基にそれらをすべて無視して「『カラマーゾフ』は父殺しの小説である」と断言しました。

そもそも結論ありきで小説を読んでいくのですからそうなるのも当然です。

たしかに小説の中で父殺しは書かれています。

フロイトがそれを『カラマーゾフ』の主題として読むのは自由ですが、だからといって『カラマーゾフ』が父殺しを主題にした小説であるとは限らないのです。

これは一見些細な違いなようにも見えますが、決定的に違います。『カラマーゾフ』は宗教や政治、思想、文化、当時のロシアの時代背景など様々な要素が複雑に絡み合ってできています。そしてドストエフスキー自身がどんな思いでその作品を書いたのか。それすらもフロイトの言う「『カラマーゾフ』は父殺しの小説である」という単純化された理由で無視されてしまうのです。

また、『カラマーゾフの兄弟』の続編では主人公のアリョーシャが皇帝打倒を目論む革命家・無神論者になるという説もありますが、上の解説にありますように、『カラマーゾフ』の成立過程を見ればそうした説の妥当性には厳しいものがあると思われます。

以前紹介したこの記事でもお話ししましたが、アリョーシャを革命家・無神論者にしようとしたのはソ連時代のイデオロギーによるものでした。

ここでは詳しくはお話しできませんが、そうしたソ連的なイデオロギーによる革命家像と、フロイトの語る父殺し、無神論は非常に親和性が高いというのは言えると思います。ソ連的イデオロギーとフロイト理論が合わさって「アリョーシャ革命家論」が生まれてきたのかもしれません。

では、引き続き『カラマーゾフ』成立の過程を見ていきましょう。

『カラマーゾフの兄弟』の萌芽2~イリインスキー・メモ

第二の萌芽、「イリインスキー」に関するメモは、『未成年』の創作ノートの中にある。

ドミートリー・イリインスキーは、ドストエフスキーが一八五〇年代初頭にオムスク監獄で知り合ったトボリスクの貴族出身の退役陸軍少尉で、父親殺しの罪で懲役二十年の刑を受けていたが、その後、『死の家の記録』執筆中の一八六二年に真犯人が見つかり、その無実が証明された。

ドストエフスキーは最初、『死の家』第一部第一章でイリインスキーを借金で首の回らない自堕落な放蕩者、いつも陽気で上機嫌、軽薄で無分別な男として描いている(ПCC,4. 15-16)。

その後、冤罪の事実が判明すると、父親殺しの濡れ衣を着せられて監獄で十年をむなしくすごした青年の悲劇に思いをいたして、同書第二部第七章で再度彼を取りあげている(TaM Жe.195)。

この事件は作家の創作意欲をいたく刺激したようで、イリインスキーに最初に会ってから二十年後、『死の家の記録』執筆の十二年後の一八七四年九月にドストエフスキーは創作ノートに彼を主人公とする説のプランを書きとめる。

「ドラマ。二十年ほど前、トボリスクでのイリインスキー事件に類するもの。二人の兄弟、老父。一方にいいなずけがいて、弟はその女にひそかに嫉妬深く惚れこんでいる。しかし、彼女は兄を愛している。だが、若い少尉補の兄は放蕩と愚行を重ねて、父と喧嘩している。父が姿を消す。数日は消息が知れない。兄弟が遺産の話をしているとき、突然、官憲が遺体を地下室から掘り出す。兄に不利な証拠があがる(弟は同居していない)。兄は裁判にかけられ、懲役を宣告される。〔……〕十二年後、弟が面会にやってくる。沈黙のうちに互いに理解しあう場面。それからさらに七年後、弟は官職にあるが、苦しんでいて、ヒポコンデリー患者。妻に自分が殺したと打ち明ける。『どうしてあんたは私に言うの?』彼は兄を訪ねる。妻も駆けつける。妻は懲役囚にひざまずき、黙っていて夫を救ってくれと哀願する。懲役囚は『俺はもう慣れてしまった』と言い、彼らは和解する。『おまえはそれでなくともすでに罰せられている』と彼は言う。弟の誕生日。客が集まっている。出てくる。私が殺した。みなは深い悲しみだと思う。最後。一人は帰ってきて、もう一人は中継監獄にいる。彼は解雇される(中傷者)。弟は兄に自分の子どもたちの父親になってくれと頼む。『正しい道に踏みだしたのだ!』」(ПCC,17・5-6)

このプランの重要性は多言を要しまい。これを見ると、すでにこのごろには物語の主筋の基本的枠組みができあがりつつあったことがわかる。

七八年春から作成され始める『カラマーゾフ』の創作ノートでも当初、ドミートリー・カラマーゾフはイリインスキー、イワン・カラマーゾフは殺人者もしくは学者と呼ばれていた(アリョーシャは白痴と呼ばれていた)。

それともう一点、ゾシマ長老の語る挿話「謎の訪問客」がイリインスキーの弟から分離して成立していることは明白である。

それ以上に注目すべきは、現実に起こった事件を素材にしながら、波乱に満ちた物語を構築していくその過程、ドストエフスキーの瞬発力に富む運動神経のよさがこのごく短いメモからも伺われる点である。

実際のイリインスキー事件は父親殺しの罪で、二十年の刑を受けていたが、のちに無実が判明するという、異常ではあるが、ごく単純なものだった。

ところが、ドストエフスキーはイリインスキーの周囲に、そのいいなずけ、真犯人の弟というたった二人の人物を配置するだけで、奸計、恋のもつれ、嫉妬、背信、罪の苦しみ、告白、贖罪、罪の赦し、苦難をへての魂の救済、兄弟の和解という感情の動きを軸に、入り組んだできごとを次々と生じせしめ、私たちがよく知る、いかにもドストエフスキー的としか言いようのない、ダイナミックな推進力を持つ悲劇を見るみるうちに作りあげていくのである。

水声社、杉里直人 『【詳注版】カラマーゾフの兄弟【注・解説・年譜編】』P206-8

※一部改行しました

フロイトはエディプス・コンプレックスが『カラマーゾフ』を生み出したと述べますが、この解説を読んでわかりますように、ドストエフスキーの父殺しは実際に起きていた事件をモチーフに構築されたものでした。

そしてそこから先に述べた「無神論」、「大罪人の生涯」のプロットと組み合わせられながら作られていったのです。

『カラマーゾフの兄弟』の萌芽3~子どもの問題の浮上ー子どもの虐待問題への関心

一八七〇年代にドストエフスキーの創作構想として急浮上したものの一つに、子どもを主人公とする小説がある。

ドストエフスキーは、これまでにもネートチカ・ネズワーノワ(同名の未完の長編小説のヒロイン)、ネリー(『虐げられた人々』)、ポーレチカ・マルメラードワ(『罪と罰』)、あるいはコーリャ・イヴォルギン(『白痴』)など、独立心が旺盛で、誇り高く生気に満ちた、忘れがたい子どもたちを何人も創造してきたが、この時期には子どもたちだけを主人公とする長編小説を構想している。

子どもたちは「自分たちの子どもの帝国を作ろうと密約」をかわし、「共和制と君主制について議論する」、彼らは獄中の少年犯罪者たち(放火犯、列車転覆犯)と連絡を取る、「子どもたちは放蕩者の無神論者だ」といったメモが残されている(ПCC,16・6)。

この構想のために、ドストエフスキーは積極的に取材におもむいてもいる。

一八七三年に、ドストエフスキーはペテルブルグ監獄の未成年犯罪者収容所を訪れて、町に放り出された少年たちの精神状態に関する資料を蒐集しているし、七七年夏にはA・Ф・コーニ―『カラマーゾフ』第九編「起訴前の取調べ」と第十二編「誤審」の執筆に際して助言を仰いだ検事―にオフタの児童補導施設を案内してもらい、長時間にわたって幼い収容者と語らっている。

さらにはぺスタロッチ、フレーべル、レフ・トルストイの教育学文献も読んでいるし、『カラマーゾフ』の執筆直前の一八七八年三月には作家で教育学者のB・B・ミハイロフに手紙を出し、子どもたちの「できごと、習慣、応答、言葉、片言隻語、特徴、家庭環境、信仰、非行、純真さ」(ПCC,30 KH.1・12)など、知ってることすべてを教えてほしいと依頼している。

このような子どもに対する持続的な関心が『カラマーゾフ』のイリューシャとコーリャ・クラソートキンを中心とする第十編「少年たち」や、エピローグでのイリューシャの葬儀の場面に結実していることはあらためて言うまでもあるまい。

子どもの主題との関連で、この時期にとくに焦点化した問題がある。「子どもの虐待」である。

ドストエフスキーは『作家の日記』で、児童虐待の罪で立件されたクロネべルグ事件やジュンコフスキー事件を取りあげている。

たとえば、前者はこんな事件だった。ワルシャワとブリュッセルで大学教育を受けた法学士クロネべルグはワルシャワである女性と恋仲になるが、結婚にはいたらず二人は別れる。

その後、その女性に子どもが生まれるものの、彼女はその子を育てられず、ジュネーヴで里子に出す。

一八七四年、クロネべルグは別の女性と結婚して、翌年子どもを引き取り、ペテルブルグに連れ帰る。

だが七歳になる女の子はジュネーヴにいる間にすっかり野生化して、父親の顔さえ見わけられない状態になってしまったと父は思いこむ。

素行不良に対するしつけという今も昔も変わらない口実で、すぐに虐待が始まる。それは「シピッツルーテン」(軍隊や監獄で懲罰のために用いられる数本の柳の枝を束ねた笞)による十五分に及ぶ折檻にエスカレートする。

あまりの残酷さに心を痛めた下女が当局に訴えでて虐待は表沙汰になり、クロネべルグは告発される。

一八七六年一月二十三~二十四日にペテルブルグ地方裁判所で陪審裁判が行なわれるが、有能な弁護士スパソーヴィチの言葉巧みな弁護もあって、無罪判決が出る。

ドストエフスキーはこの事件に強い関心を寄せ、『作家の日記』一八七六年二月第二章(ПCC, 22・ 50-73)をすべて費やして、事件それ自体にというより、詭弁と詐術をまじえながら陪審員の素朴な感情に訴えかける、弁護人の三百代言的な法廷弁論に批判を集中し、合わせて陪審制度の弊害にも矛先を向ける。

クロネべルグ事件は『カラマーゾフ』第五編第四章「反抗」で、イワン・カラマーゾフが神の創った世界の不条理さを証拠だてる事例としてあげる子どもの虐待事件の三つのうちの第一のものにほかならない。

イワンはほかに、五歳の女の子に日常的に折檻を繰り返したあげく、最後には夜中に便意が伝えられなかったからとの理由で便所に閉じこめ、うんちを顔じゅうに塗りたくり食わせる両親、投げた石が猟犬の足に当たって怪我をさせたといって、八歳の少年に犬をけしかけさせた老領主の事件をあげるが、これらはいずれも実際に起こった事件、当時の新聞・雑誌で大々的に報じられ、世間を騒がせた事件である。

水声社、杉里直人 『【詳注版】カラマーゾフの兄弟【注・解説・年譜編】』P208-9

※一部改行しました

ドストエフスキーは子どもの虐待にひどく心を痛めていました。彼が子どもたちに向ける思いを知るには『作家の日記』が非常に参考になります。この作品はドストエフスキーが何に関心を持ち、どのようなことを読者に伝えようとしていたかが明快です。

私も『作家の日記』を読んでドストエフスキーはこういう人だったのかと非常に驚いた経験があります。上の記事はその時の顛末について書いたものですが、ドストエフスキーの優しさ、子どもたちへのまなざしというものを感じられるので『作家の日記』は非常におすすめです。

『カラマーゾフの兄弟』の萌芽4~「父と子」の問題。《偶然の家族》

子どもの問題は、見方を変えれば、「父と子」の問題でもある。

ドストエフスキーはそれを《偶然の家族》と呼んで、やはり七〇年代なかばに前景化させる。

この問題のもっともまとまった論考としては『作家の日記』一八七七年七・八月第一章第二節の記事がある(ПCC. 25. 176-182)。

作家は最初にその年の夏にたまたま遭遇した不愉快な小事件を伝える。

旅の途上、汽車で乗りあわせた立派な身なりのロシア人の紳士がせがまれるままに八歳ぐらいの少年に煙草を与え、その子はもの慣れた様子でひっきりなしに煙草を吸い続けるという光景を目にする。

不愉快とはいえ、ごく些細なこのできごとに、ドストエフスキーは過渡期の社会状況に特有の頽廃を敏感に嗅ぎ取り、それをかねて論じてきた《偶然の家族》の問題へと敷衍する。

子育てに定見を持たず、怠惰、無気力、無関心に支配され、人生への普遍的な理念を見失ってしまった父親のぶざまな姿と、そんな親に偶然まかせで育てられる子どもたちの惨状、彼らを待ち受ける憂うべき将来とを、作家は具体的な情景をあれこれ想像しつつ、深く憂慮する。

《偶然の家庭》の父親たちが子どもたちに日々見せつけるであろう「下種さ加減、地位や金銭を得るための下劣な振舞い、醜悪な策謀、いまわしい奴隷根性」、さらには貧しさゆえの「小心翼々ぶり、家庭内のいざこざ、口論、非難、叱責、あるいは食い扶持の多さにゆえに子どもたちに向けて発せられる呪詛」(TaM Жe, 180)は子どもの心に消し難い汚点を残すだろう。

怠惰で意志薄弱、忍耐力に乏しい親は、子育てに際して、愛や労苦ではなく、笞の助けを借りる。「説明ではなく命令、訓戒ではなく強制」(TaM Жe, 190)が幅をきかせるのだ。

無責任な親のエゴイズムの犠牲となった子どもたちは冷笑と頑迷、ゆがんだ正義感をおのずと身につけ、やがては柔軟な心を失って、冷酷になるだろう。

彼らは「もし神聖なものが何もなければ、つまりはどんな醜悪なことをしてもかまわない」(TaM Жe, 179)と短絡するようになる。

そしてその薄汚れた思い出をポケットにたくさん詰めこんで、子どもたちが人生行路に乗りだしていかざるを得ないことを、ドストエフスキーは嘆き、「肯定的なもの、美しいものの萌芽なしに、人間は幼年時代を脱して人生に乗りだしてはならないし、肯定的なもの、美しいものの萌芽なしに次の世代を旅立たせてはならない」(TaM Жe.181)と警告を発して、感受性の鋭い子どもたちの魂こそ、偉大な思想と偉大な感情を必要とすると主張する。

ドストエフスキーがこれらの言葉を『作家の日記』にしたためたのは一八七七年の夏である。ここから『カラマーゾフの兄弟』の出発点まではほんの数歩だろう。フョードル・パーヴロヴィチが《偶然の家族》の父親の典型であることは、今や誰の目にも明らかである。

水声社、杉里直人 『【詳注版】カラマーゾフの兄弟【注・解説・年譜編】』P210-211

※一部改行しました

これまでお話ししてきた内容もすべて重要なのですが、この箇所で語られたものは特に重要です。

フロイト理論では『カラマーゾフの兄弟』の父親がドストエフスキー自身の父親がモデルであると断言していますが、実際はここで語られる《偶然の家族》の問題がそのモチーフだったのです。

さらに、そもそもドストエフスキーの父親はカラマーゾフの父親と似ていません。そのことについては前回の記事でも詳しくお話ししましたのでぜひそちらもご参照ください。

ここまで杉里直人著 『【詳注版】カラマーゾフの兄弟【注・解説・年譜編】』を参考に『カラマーゾフの兄弟』執筆の動機と流れをご紹介してきました。

これは『カラマーゾフの兄弟』そのものを読んでもなかなか見えにくいものでありますし、その解説を読んでもここまで踏み込んではなかなか語られることはありません。

ですが、今回の記事を読んで頂いて『カラマーゾフの兄弟』がどのようにして出来上がっていったのか、そしてドストエフスキーがこの小説で一体何を言おうとしていたのかが見えてきたのではないでしょうか。

まずこの小説の根本は「無神論」、「大罪人の生涯」という作品案におけるテーマにあります。

これらのタイトルだけを見れば無神論的な発想で書かれているかと思いきや、実際はその真逆であることがドストエフスキーの言葉から示されました。

そしてイリインスキーという父殺し事件の冤罪で捕らえられていた男との出会い。

子どもの虐待問題。《偶然の家族》の問題など、様々な要素が組み込まれて物語が作られていきます。

これがドストエフスキーが辿った道筋です。

こうした背景を知ると、『カラマーゾフの兄弟』がまた違って見えてきますよね。

杉里直人氏の『【詳注版】カラマーゾフの兄弟【注・解説・年譜編】』ではここからさらに『カラマーゾフ』の解説を詳しく見ていきますし、他にも様々な参考書でドストエフスキーについての解説がなされています。

その中でも入門書として特に私がおすすめしたいのは以下の三作品です。

ドストエフスキー関連の本はものすごく面白くて刺激的な本もたくさんあるのですが、入門書としてどうかと言われると正直厳しいのではないかというのが本音です。

そういう面で、これら3冊はドストエフスキーの知識がなくてもその作品の奥深さや彼の特徴、生涯を知れるので非常におすすめです。

そして『カラマーゾフの兄弟』やドストエフスキーの思想の解説書というわけではありませんが、以下の本も強くおすすめします。

こちらはドストエフスキーの奥様アンナ夫人によって書かれた回想記で、1866年に初めて出会ってから1881年に亡くなるまでのドストエフスキーの貴重な素顔を知れる作品です。私はこの回想記を読んでドストエフスキーを心の底から好きになりました。ギャンブル中毒になりすってんてんになるダメ人間ドストエフスキー。生活のために苦しみながらも執筆を続けるドストエフスキー、愛妻家、子煩悩のドストエフスキーなど、意外な素顔がたくさん見られる素晴らしい伝記です。こちらもぜひ読んでみて下さい。きっとドストエフスキーのことが好きになると思います。

おわりに~なぜ『カラマーゾフの兄弟』は難しい?

さて、ここまで『カラマーゾフの兄弟』について長々とお話してきましたが、いかがでしたでしょうか。

この作品においては賛否両論様々な意見が飛び交っています。

「難しい」「面白くない」「つまらない」「神の問題など現代日本に関係ないから不要」「読む価値などない」などなど様々な意見がネットでもすぐ出てきます。

ですが、ここまでこの記事を読んで頂いた皆さんならきっとわかって頂けるはずです。

「ドストエフスキーがどれだけ本気でこの作品に向き合っていたのか、そして彼が読者に対してどんなメッセージを送ろうとしていたか」を。

それがわかればこの作品に対する見方は自ずと決まってきますよね。

それにそもそもこの作品はロシアの知識人を対象として書かれた本です。ですのである程度の知識や能力が必要とされています。つまり、ロシア正教の知識や当時のヨーロッパ・ロシア事情にも通じていることが前提条件なのです。

ですので、この作品はそもそも現代の日本人がいきなり読んで簡単にわかるような作品ではないのです。もちろん、前知識がなくても読むことはできます。前知識がなくともその面白さ、奥深さを感じさせるパワーがこの作品にはあります。さすがは世界を代表する古典の傑作です。ですが、もしこの本を面白く読めなくても何ら自分を卑下する必要はないのです。わからなくて当たり前と思うとかなり見え方が変わってきますよね。

以前この記事でお話ししましたように、私が『カラマーゾフの兄弟』を読んで衝撃を受けたのは、私が僧侶であり、宗教的な問題を抱えていたからです。

宗教に対する知識があり、自分が宗教者としてどのように生きていくかという悩みを抱えていたがためにこの作品がとてつもなく面白く感じられたのでした。

では、宗教に関心がない方にはこの作品は意味をなさないのか。

決してそんなことはありません。

宗教を学ぶことは人間の歴史・文化、いや、人間そのものを学ぶことであります。

当時の人たちはどんなことを思い、悩み、苦しんでいたのか。そしてそこからどのような希望を持とうとしていたのか。

それをこの小説で考えていくことができます。宗教の問題を語ったあの大審問官の章も、人間のあり方の根源へと突き進んでいった洞察です。

もちろん、ロシア正教の知識や当時のヨーロッパ、ロシアの時代背景、ドストエフスキー自身のことを知っていた方がより楽しめるのは確かです。

ですので、上に挙げた参考書などを読んでみたり、「神のことなんてどうでもいい」と切り捨てずに、じっくりと考えてみること。それがこの小説をもっと味わう秘訣であると思います。宗教の問題は馬鹿にできません。宗教はいまだに世界の動きに大きな影響を与えています。宗教の難しいところは一見宗教に見えないものも宗教的な原理で動いているということが多々ある点です。

日本人の多くの方が「私は無宗教です」と述べられるのですが、私から見ると日本人ほど宗教的な人達はいないのではないかと思っています。日本人の言う「無宗教」は「ある特定の宗教を熱心に信仰しているわけではありません」という意味であって、実際は明らかに宗教的な側面を強く持っています。

長くなってしまうのでこの記事ではそのことについては詳しくお話しできませんが、当ブログでは「宗教とは何か」という問題をとても大切にしています。ブログ内にはこのことについての記事も色々ありますのでぜひご覧になって頂けたらと思います。私の2019年の世界一周記はまさしく「宗教とは何か」をテーマに書かれたものです。ぜひそちらも読んで頂けましたら宗教がいかに私たちの身近なところにあるかも感じて頂けるのではないかと思います。

宗教は私たちが思う以上に私たちの心や行動に影響を与えています。それを学ぶことで私たちが生きる世界の成り立ちや歴史も学ぶことができます。そして何より、今を生きる私たちのあり方そのものを見つめ直す機会になります。それを無駄と切り捨てるのはもったいない気がしませんか?

『カラマーゾフの兄弟』はそういう素晴らしい機会を与えてくれる作品です。

もちろん、宗教の面だけではなく、様々な側面からこの作品を読むことができます。宗教を気にしなくても十分読むことは可能です。ですが、ロシア正教におけるキリストの存在をとことんまで突き詰め、それを作品にしようとしていたドストエフスキーの意志を汲み取ることも大切なのではないでしょうか。

以上、「『カラマーゾフの兄弟』は何をテーマに書かれ、どのような背景で書かれたのか~ドストエフスキーがこの小説で伝えたかったこととは」でした。

Amazon商品ページはこちら↓

前の記事はこちら

関連記事

コメント