(7)客だらけのドストエフスキー家の家庭状況と新婚早々親類からの嫁いびりに苦しむアンナ夫人

(7)客だらけのドストエフスキー家の家庭状況と新婚早々親類からの嫁いびりに苦しむアンナ夫人

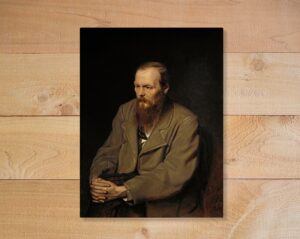

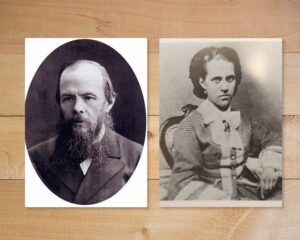

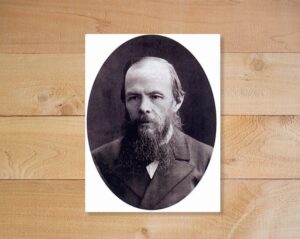

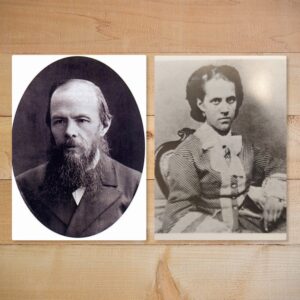

これまでドストエフスキーの経済状況、持病のてんかんと彼の抱える問題を見てきたがその最後に彼の家庭環境を見ていくことにする。実はアンナ夫人の新婚生活にとって最も苦しかったのがこの家庭環境だったのである。嫁いびりといえばよくあることのように思えてしまうかもしれないがそこはあのドストエフスキー家である。やはり一筋縄ではいかない苦難をアンナ夫人は味わうこととなった。

ではまずそんなドストエフスキーの家庭環境について見ていこう。

結婚生活の最初の何週間かが台なしになり、せっかくの「蜜月」を悲しい口惜しい気もちで思い出さざるをえない嫌なことといさかいとが始まったのもこのみじめな週のことだった。

わかりやすいように、新しい生活について述べてみよう。フョードル・ミハイロヴィチは夜仕事をするたちで、早く寝つかれないで本を読むので、起きるのはおそかった。わたしは十時までには支度して、料理女といっしょにセンナヤ広場へ買出しに出かける。(中略)

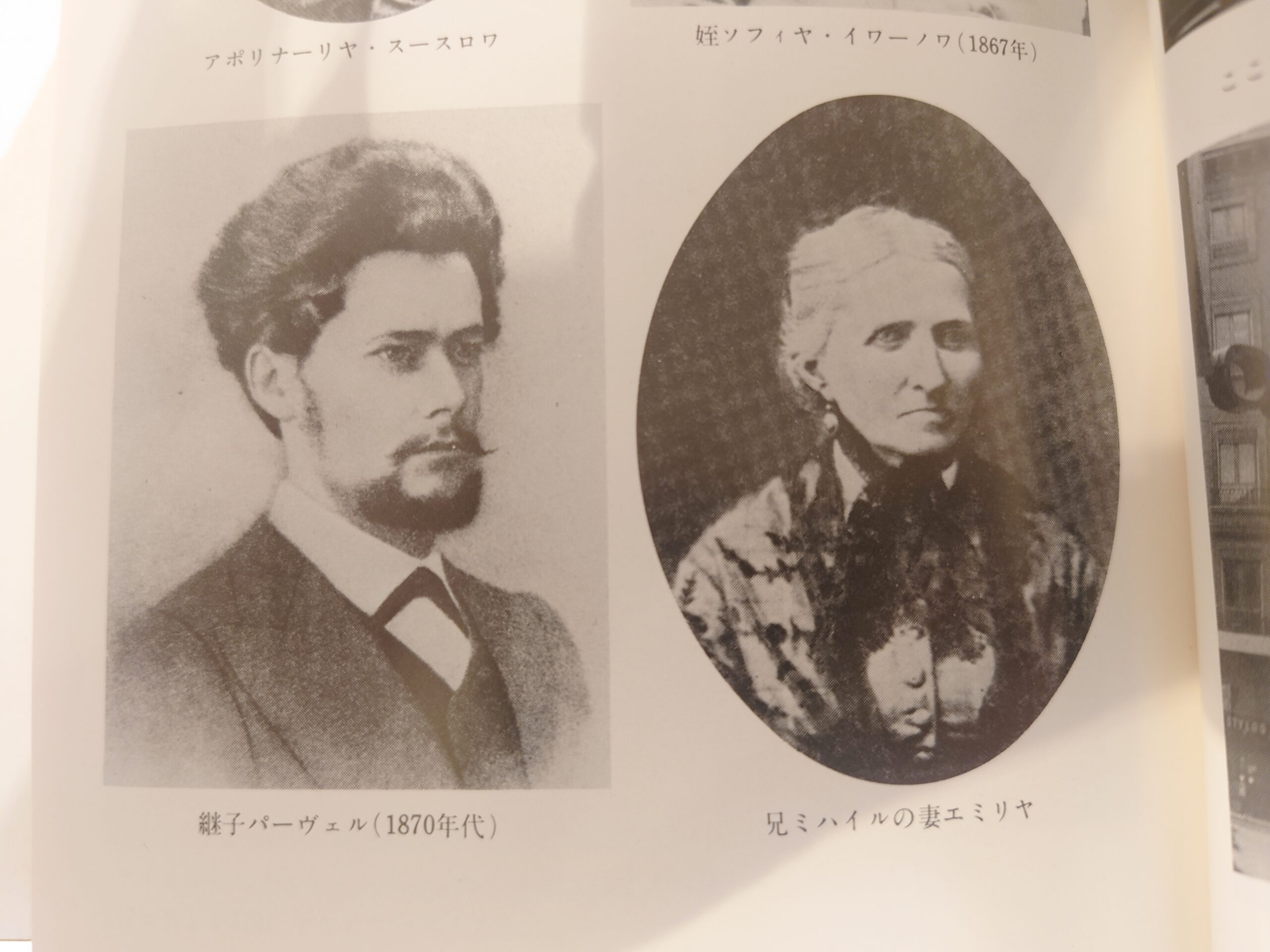

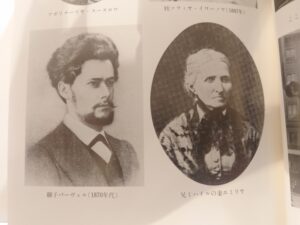

十一時には帰ってくると、たいていは、姪のカーチャ・ドストエフスカヤが来ている。彼女は十五くらい、美しい黒いひとみの、明るい亜麻いろの長いおさげを二本背に垂らしたたいへんかわいらしい娘だった。母親のエミリヤ・フョードロヴナは何度かわたしに、カーチャはわたしを好いているから仕込んでもらいたいと言った。おせじとはわかっていても、ではなるたけちょいちょいよこすようにと答えないわけにはいかなかった。

カーチャは、することはなし、家にいても退屈なので、朝の散歩からまっすぐわが家にやってきた。うちから五分のところに住んでいたから来やすかったのだ。

昼までには、パーヴェル・アレクサンドルヴィチをたずねてミーシャ・ドストエフスキーがやってくる。夫の甥の十七歳になる少年で、音楽院でヴァイオリンを習ったかえりに立ち寄るのだ。もちろん、わたしは彼のために朝食を取っておく。

すぐれたピアニストの甥のフョードル・ミハイロヴィチも、しょっちゅうやって来た。

二時になると夫の友人や知人が集まりはじめる。その人たちは、夫がいま急ぎの仕事をしていないのを知っていて、ちょいちょい来てもかまわないと思っていた。

夕食には、しばしば、エミリヤ・フョードロヴナが姿を見せ、夫の弟のニコライ・ミハイロヴィチがやってくる。妹のアレクサンドラ・ゴレノフスカヤと彼女のつれあいのニコライ・イワーノヴィチも来た。

食事のあと、みんなは、たいてい十時、十一時まで居残って夜をすごした。毎日がこんなぐあいで、他人や身内がわが家に絶えることがなかった。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

みすず書房、アンナ・ドストエフスカヤ、松下裕訳『回想のドストエフスキー』P118-119

ずいぶんとたくさんの人物が登場してくることに皆さんもきっと驚かれたのではないだろうか。ここではその一人一人の名前を覚える必要はないが、ドストエフスキー家がいかに来客が多かったかというのが伝わったことと思う。そんな毎日にアンナ夫人は次のように漏らしている。

わたし自身は、昔ふうの客好きな家庭で育ったが、客が来るのは日曜か祭日かに限られていた。だから朝から晩まで「ごちそうし」「楽しませ」なければならぬ「ひっきりなしの」この客の応対は、なんとも苦痛だった。

まして、ドストエフスキー家の若い連中や義理の息子は、わたしとは年も離れていて、そのころのわたしの目ざすところともちがっていたから、なおさらだった。

逆に、夫の友人、知人、文学仲間―マーイコフ、アヴェルキエフ、ストラーホフ、ミリュコフ、ドルゴモスチェフその他の人々は、とてもおもしろかった。わたしはそれまで知らなかった文壇のことに興味津々だった。この人たちと話したり論じあったりしてみたかったし、できればこの人たちのする話が聞いてみたかった。残念ながら、めったにそれはかなえられなかった。若い連中が退屈しているのを見ると、夫がわたしにささやくのだった。「ねえ、アーネチカ、みんな退屈がってるよ、あっちに連れてって、なにかして楽しませてやりなさい」。そこでわたしは、口実をもうけて、みんなを連れだして、がまんしながら何かして「楽しませる」のだった。

絶え間のないお客で好きな仕事をする時間がまるでなく、これはわたしにとって大きな損失だったが、そのためにもいらいらさせられた。まる一カ月というもの一冊の本も読んでいなかったし、ぜひ完全にも心にしたいと思っていた速記の規則的な勉強もしていなかった。それを考えるとくやしくてならなかった。

だが一番つらかったのは、いつも客が来てすっかり時間をとられて、愛する夫とふたりきりですごすことができないことだった。昼間すこしでも時間ができると、わたしは書斎の夫のそばに行ったが、するとすぐに、だれかがはいってくるか、家事のことで呼ばれるかするのだった。あれほど大事にしていた夕べの夫との話も忘れたようにしなくなった。雑事とおおぜいの客の応対とおしゃべりのうちに一日が過ぎて夜になると、夫もわたしも疲れはて、わたしはねむくなり、夫は息ぬきできるようなおもしろい本にむかうのだった。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

みすず書房、アンナ・ドストエフスカヤ、松下裕訳『回想のドストエフスキー』P119-120

『若い連中が退屈しているのを見ると、夫がわたしにささやくのだった。「ねえ、アーネチカ、みんな退屈がってるよ、あっちに連れてって、なにかして楽しませてやりなさい」。』

ドストエフスキーのこの言葉は当時の彼の家族観、妻へ求めていたことが端的に現れている。ドストエフスキーは何の悪気もなしにアンナ夫人に客をもてなすように頼んだ。だがそれによってアンナ夫人が傷ついていることに彼はまだ気づくことができなかったのである。小説ではあんなに人間心理の奥に入り込めるのに、一番身近な存在である妻の気持ちが見えていないというのは何たる皮肉だろう。だがこれが古今東西の人間の悲劇なのかもしれない。

さて、そんな客だらけのドストエフスキー家であったが、アンナ夫人にとって一番辛かったのはこうした客対応ではなかった。敵は内にあったのである。

アンナ夫人は『回想のドストエフスキー』の中でわざわざ「家庭の中の敵」という章を作ってその「嫁いびり」について記している。アンナ夫人が新婚生活で最も苦しんだその嫁いびりの様子をこれから見ていこう。

けれども、夫の身内のものがしかける不愉快なことが加わりさえしなければ、時がたつにつれて、わたしはこの生活に慣れもし、好きな仕事をする或る程度の自由と時間を見つけることもできたことだろう。

兄嫁のエミリヤ・フョードロヴナ・ドストエフスカヤは、人はいいが思慮の浅い女性だった。夫に先立たれてからは、彼女とその家族の世話はフョードル・ミハイロヴィチが引き受けるようになったが、彼女はそれを当然のことと考えていた。

彼女は、フョードル・ミハイロヴィチが結婚を望んでいるのを知ると大きなショックを受け、婚約のあいだじゅう、わたしに敵意ある態度を取りつづけた。

結婚式をあげてからは、この事実が動かせないことをみとめて、とくにわたしが彼女の子どもたちによくするのを見てからは、わりあい愛想よくなった。

彼女は毎日のようにやってきて、いっぱしの主婦気取りで、たえずわたしに家事の注意をするのだった。それは、親切気とわたしのためを思ってのことからだったかもしれない。

だが教えてくれるのは、いつも夫のいるところでだったし、いやでならなかったのは、家政のまずさと不経済を夫にわざと見せつけるようにすることだった。そしていっそう腹立たしかったのは、ことごとに先妻の例を持ちだして、彼女とくらべてはわたしのまずさを指摘することだった。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

みすず書房、アンナ・ドストエフスカヤ、松下裕訳『回想のドストエフスキー』P120-121

ドストエフスキーの兄ミハイルは1864年に急死した。その奥様と子供の面倒をドストエフスキーは見ていたのである。その奥様がここで語られるエミリヤだ。ドストエフスキーが結婚してしまえば自分たちへの送金が減ってしまうかもしれない、それは困るということだ。だからこそアンナ夫人を目の敵にしたのである。

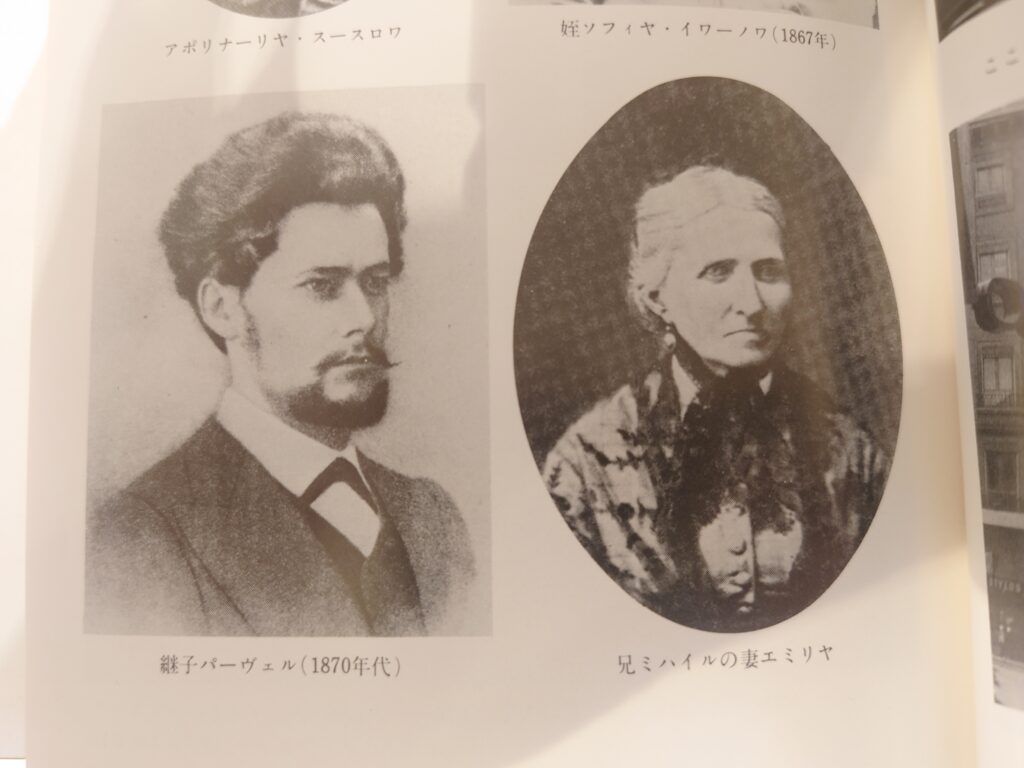

しかしこのエミリヤ夫人のいびりをさらに超える脅威があった。それがドストエフスキーの前妻マリアの連れ子パーヴェルの存在だった。

パーヴェルはドストエフスキーの実子ではない。「(1)妻アンナ夫人と出会うまでのドストエフスキー(1821~1866年「誕生から『罪と罰』頃まで)をざっくりとご紹介」の記事でお話ししたように、彼の一人目の妻マリアは前夫との間に子供がいた。その子供がこのパーヴェルなのである。

だがドストエフスキーはこのパーヴェルを愛した。いや、甘やかしすぎた・・・そのせいもありパーヴェルは甘え切ったとんでもない無頼漢になってしまった。現実は小説より奇なりを地で行く男の出来上がりである。

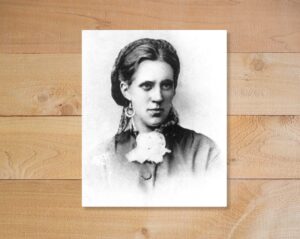

アンナ夫人はそんなパーヴェルの人となりについて次のように語っている。

エミリヤ・フョードロヴナがしょっちゅうわたしに注意することと、そのいささか先輩ぶった調子とは不愉快なだけだったが、パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチがあえてした無礼と無作法にいたっては、とうてい我慢できないものだった。

わたしは、結婚すれば、フョードル・ミハイロヴィチの義理の息子がいっしょに暮すことになるのは、もちろん心得ていた。わかれて暮すほどの余裕はなかったし、夫は彼の性格が固まらぬうちは自分の影響下に置いておきたいと望んでいた。

わたしは若かったので、新所帯に赤の他人がはいりこんできても不愉快だなどとは思いもしなかった。そのうえ、夫は義理の息子を愛していて、なじんでもいたので、別れるのがつらくて別居しようと言いたがらないのだと思ったくらいだった。それどころか、自分と同じ年の人間が一つ家にいると、夫のいろいろな習慣(まだ知らない習慣がたくさんあった)を教えてくれ、それによってわたしが夫の従来の生活をそれほど乱さなくてもすむだろうと思われた。

*パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチはわたしより数カ月若いだけだった。

パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチ・イサーエフが、愚かな人間あるいは意地のわるい人間だったとは言いたくない。彼にとって何より不幸だったのは、自分の置かれた立場を一度も理解しなかったことだ。彼は、幼いときから、親類中のものや夫の友人たちから親切と好意を示されるのに慣れきって、それを当然のことのように思いこみ、こんなふうに人々が親切にしてくれることが、自分自身の力でよりもむしろフョードル・ミハイロヴィチのおかげだということを決して理解できなかった。

好意をもってくれた人々が目をかけてくれることに感謝し報いるどころか、軽々しくふるまい、だれにでも、ぞんざいな、また生意気な態度をとったので、これらの人々を悲しませたり怒らせたりするだけだった。

とりわけあの立派なマーイコフは、パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチからずいぶんたびたび不愉快をこうむったが我慢して(もちろん、フョードル・ミハイロヴィチのために)、あらゆる面で面倒を見てくれたが、残念ながらその甲斐はなかった。

(中略)

彼は夫のことをいつも「父」と呼び、自分を「実の息子」のように言っていたが、その義理の父にたいしてまったく同様に、ぞんざいで、おうへいな態度を取っていた。彼は一八四六年アストラハン生まれで、夫は一八四九年までぺテルブルグから出たことがなかったので、実の息子ということはありえなかった。

パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチは、十二の年から夫に育てられ、いつくしまれてきたのに、「父」は自分のためにだけ生きて、働き、金をかせぐべきもの、と信じきっていた。彼自身はといえば、なに一つ夫を助けもせず、生活を楽にさせたことはなかったばかりか、逆に軽率なふるまい、思慮のない態度で夫をいらいらさせ、身内のものがみな認めていたとおり、彼に発作をおこさせもしたのだ。

パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチは、夫のことを「時代おくれの老いぼれ」と呼んでいたが、夫が自分の幸せを望んでいるのを「ばかげている」と言って、それを親戚のものに公言していた。

彼の目にはわたしは簒奪者と映っていた。またわたしは、夫が文学の仕事に追われて、当然家事にかかずらうことなどできないので、これまで彼がまったく主人顔でいられたわが家に、強引に割りこんできた女というふうに映っていた。

こう考えてこそ、彼のわたしにたいする悪意も理解できる。彼は、わたしたちの結婚をはばむことはできないのがわかると、わたしがこの結婚に耐えられぬようにしようとした。たえず嫌がらせをしたり、ロげんかをしかけたり、夫にわたしのことを中傷したりすれば、ふたりは仲がわるくなり、離婚することになるかもしれないと期待したのだ。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

みすず書房、アンナ・ドストエフスカヤ、松下裕訳『回想のドストエフスキー』P121-122

アンナ夫人による伝記『回想のドストエフスキー』ではこのパーヴェルの仕打ちがこれから先何度も何度も出てくるが、そのいくつかを引き続き見ていこう。

パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチのした意地のわるい小細工には、まったく限りがなかった。

あるときは、フョードル・ミハイロヴィチが食堂に姿をあらわすまえにクリームを飲んでしまい、仕方なく大急ぎで店に買いにやらせたが、もちろん質のわるいものしかない。そのあいだ夫はずっとコーヒーを待っていなければならなかった。

あるときは、夕食の直前に鳥をたいらげて、三人に二羽しかなくてこまったことがあった。ゆうべまでは幾箱もあったのに、家中からマッチが姿を消したこともあった。そのたびに夫はひどくいらだって、フェドーシャをしかりつけるが、このごたごたを起こした張本人は、肩をすくめて、こう言うのだった。「ねえ、パパ、ぼくが家をとりしきっていたころは、こんなごたごたはありませんでしたよね」。みんなわたしのせいだ、もっと正確に言うと、わたしの家政のまずさが原因、というわけだった。

パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチのやり方はたいてい決まっていた。

夫がいるところでは、わたしに殊のほかていねいで、皿を渡してくれたり、女中をさがしまわって呼んでくれたり、落としたナプキンをひろってくれたり、というぐあいだった。夫はそれを見て、女たち、なかでもわたしのおかげで(彼は、カーチャとエミリヤ・フョードロヴナの親子とは親しくするのを避けていたので)、パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチはよくなった、行儀もだんだん改まってきた、と二度ばかりも言ったくらいだった。

だが、彼のわたしにたいする態度は、夫が部屋を出て行ったとたんに一変するのだった。

あるときは、他人のまえで、以前はすべてうまくいっていたと言って、わたしの家政を非難した。あるときは、わたしが金を使いすぎる、金は自分たち「みんなのものなのに」と言った。またあるときは、家庭のなかで虐待されている犠牲者をよそおって、いままで家庭で幸福に暮し重んぜられてきたのに、「孤児」として苦しい立場におかれているとしゃべりたてた。

―突然よそ者が(わたしのことだ。妻が?)家にはいりこんで、実権をにぎり、家庭の元締めとなろうとしている。あたらしく来た主婦は、「息子」をいじめ、いやがらせをし、暮しをじゃましだした。食べるたびにいやらしい目でじろじろ見られ、おちおち食事もできない。思えば今まではなんと幸福だったことだろう、もう一度そうなってほしい、自分は「父親」を彼女にとられたくない、などなどと言って。ドストエフスキー家の若い連中はわたしをかばうほどの力はなかった。年長の者は彼を笑いものにしたが、それは自分たちを守ろうとするときだけだった。

パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチは、自分の「父親」を取られないために、ほとんど毎朝、夫が新聞を読み始めるが早いか書斎にはいって行った。ときどき夫のしかりつける声が聞こえ、パーヴェル・アレクサンドロヴィチが書斎から飛びだして来ることがあった。彼はちょっとどぎまぎして、「おとうさん」はいそがしそうで、じゃましたくなかったから、などと言うのだった。

またあるときは、長いこと書斎にいて、得意気に出てくるなり、ふるえているフェドーシャに何ごとかを言いつける。こんなふうに二人が話したあとでは、いつも夫はわたしにこう言った。「アーネチカ、パーシャとけんかするのはおよしよ。おこらせないほうがいいよ、いい青年なんだから」。「パーシャ」はなぜわたしのことに腹を立てているのか、なんと言ってこぼしたのかと聞くと、夫は、「みんな聞きたくないような、くだらぬことばかりだ」、と言って「パーシャ」を大目に見てくれるようにとたのむのだった。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

みすず書房、アンナ・ドストエフスカヤ、松下裕訳『回想のドストエフスキー』P124-126

この箇所を読んで皆さんもこう思ったに違いない。

「ドストエフスキーよ、あなたって人は・・・!」

ひっきりなしに来る客の応対をアンナ夫人に任せた時と一緒である。いや、それよりはるかにたちが悪い。

父の前ではいい顔を見せるパーヴェルがその裏で何をやっているのか全く気付いていない。

そしてアンナ夫人の気持ちを知ろうともしない。

心理描写の鬼ドストエフスキーも家庭ではどうしようもないただの夫にすぎないのである。

誰にも理解されず、孤独を味わうアンナ夫人はいよいよ精神的に追い詰められていく。

そしてついにコップの水が溢れるように、その時は来た。

彼女は悲しみあまり泣き崩れてしまうのである。そしてこれが彼らの4年にもわたる西欧放浪のきっかけとなるのだ。

続く

主要参考図書はこちら↓

次の記事はこちら

前の記事はこちら

ドストエフスキー年表はこちら

ドストエフスキーのおすすめ書籍一覧はこちら

「おすすめドストエフスキー伝記一覧」

「おすすめドストエフスキー解説書一覧」

「ドストエフスキーとキリスト教のおすすめ解説書一覧」

関連記事

コメント