(20)ドストエフスキー夫妻のヴヴェイ滞在~悲しみのジュネーブを去り、愛娘の死を悼み暮らした夏

【スイス旅行記】(20)ドストエフスキー夫妻のヴヴェイ滞在~悲しみのジュネーブを去り、愛娘の死を悼み暮らした夏

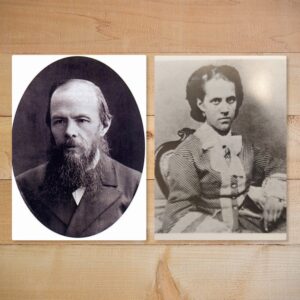

生後3カ月で亡くなってしまった最愛の娘ソーニャ。二人の悲しみはあまりに大きく、もはやソーニャの面影が残るジュネーブにいられなくなってなってしまう・・・

なにもかもソーニャの思い出の種でないものはないジュネーヴに、これ以上いつづけることは考えられなかった。

そこでわたしたちは、以前からそのつもりでいた同じジュネーヴ湖畔のヴヴェーにさっそく移ることにした。

それにしても余裕がなくて、夫がほとんど憎みはじめたほどのスイスを離れてしまえないのが残念だった。

夫はソーネチカの死を、ジュネーヴの変りやすいよくない天候、医者のつよすぎる自信、付添い女の不手際のせいにした。

夫はもともとスイス人があまり好きでなかったうえに、わたしたちがひどく悲しんでいたときにいろいろな人から受けた薄情な扱いで、いっそうこの反感がつよまった。近所の人たちは不幸を知りながら、神経にさわるからそんなに泣かないでくれとわたしに言ってよこしたりした。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

みすず書房、アンナ・ドストエフスカヤ、松下裕訳『回想のドストエフスキー』P195-196

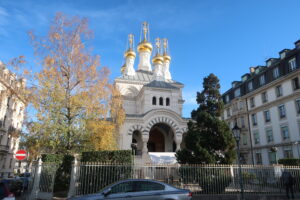

ヴヴェイはレヴァン湖の美しい景観が有名な保養地で、晩年のチャップリンがここで過ごしたことでも有名だ。ドストエフスキー夫妻は1868年の夏をこの街で過ごすことになる。

荷物を船に積みこみ、かわいい娘の墓にふたりで最後の別れに行って花輪をささげたもの悲しい日のことは、忘れることができない。わたしたちは一時間も墓のまえにひざまずいて、ソーニャを思って涙を流した。そしてひとり彼女を残して、その最後の安らぎの場所を振りかえり振りかえり立ち去った。

わたしたちが乗ることになったのは貨物船だったので、まわりには船客はほとんどいなかった。

その日は暖いが曇り日で、わたしたちの気分と同じようだった。墓に別れを告げてきたなごりで、ひどく動揺していたのだろう、そのときはじめて(めったに愚痴をこぼさない人だったが)、一生苦しめられどおしの運命のつれなさをひどくなげくのをわたしは聞いた。

昔のことを思い出しながら、やさしかった愛する母親のなくなったあとの悲しい孤独な青春について話してきかせたり、はじめ自分の才能をみとめながら、のちになってさんざんひどい扱いをした文壇仲間の嘲笑ぶりを思い出したりした。四年間というもの、どれほどひどい苦しみをなめたかしれぬ懲役のことも思い出した。

マリヤ・ドミートリエヴナとの結婚で、長いあいだの願いだった家庭の幸福をえようと夢みたが、悲しいかな、それはかなえられなかったという話もした。二人のあいだには子どもはなく、彼女の「奇妙な、疑りぶかい、病的に空想的な性格」のおかげで、彼女との生活は幸せではなかったという。

いままた、「実の子にめぐまれるという大きな、たった一つの人間らしい幸福」がおとずれ、この幸福を大事にしようと思いがけた矢先きに、苛酷な運命は、見のがさず、あれほどかわいがっていたちいさな命を取りあげてしまった!身内のものや親しい人たちから受けたつらい侮辱をこれまでじっと耐え忍んでこなければならなかった話を、これほどつぶさに、ときには感動的なくらいくわしく話してくれたことは後にも先きにもなかった。

*フョードル・ミハイロヴィチは、こういう言葉で、最初の妻の性質を、一八六五年三月三十一日づけのヴランゲリ男爵あての手紙で述べている。

**一八六六年二月十八日づけヴランゲリあての手紙。わたしは、自分たちにあたえられた試練をだまって受け入れるよう慰めようとしたが、そのあふれるような心の悲しみは、たえず苦しめられてきたこれまでの運命を嘆きでもしなければ慰められないようだった。わたしは、なんと悲しい人生だろうと不幸な夫に心から同情して、いっしょに涙を流さぬわけにはいかなかった。ともに分かちあったふかい悲しみと、痛ましい心の奥底をさらけだしてみせてくれた誠意のこもった話とは、ふたりをいっそうつよく結びつけるかのようだった。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

みすず書房、アンナ・ドストエフスカヤ、松下裕訳『回想のドストエフスキー』P196-197

痛ましいほどのドストエフスキーの悲しみが伝わってくる・・・だが、次の箇所では子を失った父親ドストエフスキーの嘆きがさらに強い言葉で記されている。引き続き見ていこう。

十四年間の結婚生活のなかで、一八六八年にヴヴェーですごした夏ほど悲しい時はなかった。人生は停止してしまったかのようだった。あらゆる思いや話はみな、ソーニャの思い出ばかりで、彼女が元気でいて生活を明るくしていた幸福だったころのことだけに集まるのだった。

ちいさな子を見かけるごとに、死んだ子のことが思い出された。これ以上苦しみたくなかったので、わたしたちは山のなかをあちこち散歩した。山のなかなら、心をゆさぶられる子どもたちに出会う心配もなかった。

わたしもこの悲しみに耐えることはつらくて、娘のことを思い出してどれほど涙をこぼしたことだろう。けれども心の奥では、慈悲ふかい神が二人の苦しみをあわれんで、もう一度子どもをさずけてくださるにちがいないと望みを失わず、このことを熱心に祈った。

わたしの母も孫娘を失って嘆き悲しんでいたが、やはりもう一度子どもを生むという希望をかけて、わたしを慰めようとした。こうして祈りと希望によって、わたしの悲嘆はすこしずつやわらいでいった。

だが、夫の場合はそうはいかなかった。そして彼の気もちのあり方に、ほんとうに驚かされるようになってきた。それは、夫のマーイコフあての(六月二十二日づけの)手紙のはしに夫人への挨拶を書きそえるために、それを読んだときのことだった。

「時がたてばたつほど、思い出はますます心を焼くようで、亡くなったソーニャの面影がますますはっきりと浮かんできます。ほんとうに耐えがたくなる瞬間がよくあります。彼女はもうわたしがわかるようになっていました。あの子が亡くなる日のことです。あと二時間ほどで死んでしまうとは夢にも知りませんでしたので、新聞を読みに出かけようとすると、彼女はちいさな目でわたしを追い、じっとわたしを見つめたのです。いまでもそれが目に焼きついて、いっそうありありと見えてきます。わたしは決して忘れることができません。そしていつまでも苦しみつづけるでしょう。たとえ次の子が生まれるとしても、かわいがることができるかどうか、どうしてかわいがったらいいかわかりません。わたしはソーニャがほしい。あの子はもういない、自分は二度とあの子にめぐり会うことができない。このことが納得できないのです」

母の慰めにも、夫は同じような言葉で答えた。この沈みきった夫の気分がとても不安で、わたしは悲しい思いでこう考えた。もし神がもう一度子どもを授けられても、はたして夫は、その子をかわいがって、ソーニャが生まれたときと同じように幸福でいられるだろうか、と。家庭のなかはまるで黒いとばりがおりたように陰鬱で物悲しかった。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

みすず書房、アンナ・ドストエフスカヤ、松下裕訳『回想のドストエフスキー』P197-198

「わたしはソーニャがほしい。あの子はもういない、自分は二度とあの子にめぐり会うことができない。このことが納得できないのです」

あぁ・・・なんて痛ましい言葉なのだろう。

もうあの子には会えない。次の子ができたとしても、あの子にはもう、二度と会えないのだ・・・

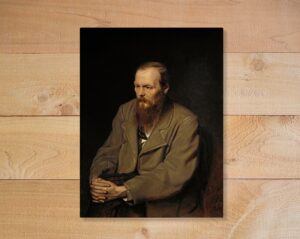

このドストエフスキーの嘆きが実は晩年の『カラマーゾフの兄弟』にも繋がってくるのである。少し込み入った話になるがモチューリスキーの『評伝ドストエフスキー』ではこのことについて次のように語られている。ドストエフスキーとキリスト教についての非常に重要なつながりがここに書かれているのでぜひ紹介したい。モチューリスキーはアンナ夫人が上で述べた手紙よりも一月前の手紙を引用し、次のように述べる。

父親はマイコフあての手紙に自分の悲しみをぶちまけている。苦悩にみちたこの文章を涙なしに読むことはできない。

「わたしのソーニャは亡くなり、三日まえに葬りました……ああ、アポロン・ニコラーエヴィチ、初めての子どもにたいするわたしの愛情がたとえ滑稽であってもかまいません。祝いを言ってくれた多くの人に答えてわたしは手紙でいろいろ彼女について滑稽な言葉を並べましたが、それでもかまいません。それらの人の目に滑稽にうつったのは、ただわたしだけなのですから。あなたには、あなたには書くことを恐れません。あの生まれて三カ月にしかならないいたいけなもの、あんなに不憫で、あんなにちっぽけなものは、わたしにはもう個性と性格をそなえた一個の人間だったのです。彼女はわたしの見分けがつきはじめて、わたしが好きになり、わたしがそばへ寄って行くとにこにこ笑っていました。わたしが自分のおかしな声で歌ってやると、あの子はそれを喜んで聞いていました。わたしがロづけしてやっても、泣きもせず、顔をしかめもしませんでした。わたしが寄って行くと泣きやみました。ところが今、みんなはわたしを慰めてくれようとして、お子さんはまたお出来になりますよと言ってくれます。でも、ソーニャはどこにいるのでしょうか。あの小さな人間はどこにいるのでしょうか。わたしはあえて申しますが、彼女が生きていてくれるためなら、十字架の苦しみさえ受けてみせます」(一八六八年五月十八日づけ)

ドストエフスキーは、聖書のなかでは何よりも「ヨブ記」を愛した。

彼自身、真実について神と争うヨブその人だった。彼もまたヨブのように、主から信仰の大きな試練を課されたのだ。「大審問官伝説」の作者のようには、だれひとりとして、これほど果敢に神と格闘した者はいなかったし、これほど大胆不敵に世界秩序の正当性について神に問いかけた者はいなかった。また、たぶんこれほど主を愛した者もいなかった。

旧約聖書の義人は、新しい子どもたちが生まれると慰められ、亡くなった子どもたちのことを忘れてしまう。ところがヨブ=ドストエフスキーは、そうすることはできなかった。人間の魂は宇宙全体よりも貴い。どんな「世界調和」がひとつの魂の喪失を埋めあわせられるだろうか。たとえそれがどんなに小さい不憫な存在だとしても。どんな「地上の楽園」が、幼な子を亡くした父親の心の苦しみを和らげられるだろうか。「でも、ソーニャはどこにいるのでしょうか」

ドストエフスキーの私的な悲しみから、イワン・カラマーゾフの反逆が生まれ育って行った。「世界調和」も「幼な子の涙」の一滴で微塵に砕け散る。ドストエフスキーは、三カ月のわが子の顔、唯一無二の、永遠の顔を見ている。そして人格の啓示は、人格の復活の問題を、心をゆるがすような力で彼のまえに提出したのだった(「カラマーゾフ兄弟」のテーマ)

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

筑摩書房、コンスタンチン・モチューリスキー、松下裕・松下恭子訳『評伝ドストエフスキー』P362-363

キリスト教の聖書の話が出てきて少し難しく感じられた方も多いと思う。『ヨブ記』は旧約聖書に説かれたもので、「何も悪いことをしていない善人が悲惨な目に遭うことをどう考えたらいいのか」という問題を提起している説話だ。サタンによって善人ヨブはある日突然大切な息子たちと財産を全て失ってしまう。そしてさらには自らの体まで病に侵されてしまう。だが、それでもなお神への信仰を捨てなかったため、最後の最後に神は彼を救い、新たな子供たちと財産を与えた。

だが、これにドストエフスキーは「否!」と答えたのである。「私にはそんな救いは認められない」と。

たとえ新たな子を授けられようと、「あのソーニャ」はどうなるというのか。あの子にはもう二度と会えないのだ。あの子は未来の幸せの生贄だとでも言うのか。あの子自身に救いが与えられないならば、私の救いなど何になるのだろう。そうドストエフスキーは問うのである。

ここでモチューリスキーが言うように、ドストエフスキーは生涯『ヨブ記』を愛読した。1875年のドイツ、バート・エムス滞在の折にも「ヨブ記を読んでいるが、この書はわたしに病的な感激をよび起こすのだ。(中略)この本はアーニャ、不思議な話だが、わたしの生涯で深い感銘を受けた最初の書物の一つだ(6月10日付)」とドストエフスキーはアンナ夫人への手紙に書いている。それほどドストフスキーにとって『ヨブ記』という存在は巨大なものだったのである。こう見てみると「そんな救いなど認めない」と言うドストエフスキーはキリスト教を批判する人間のように思われるかもしれない。だが、信仰とはただ盲信するだけではない。この信仰と疑いの絶え間ない戦いにこそその本質があるのだ。このことについて話し出すと長くなってしまうのでここでは控えるが、ドストエフスキーにとって自分がキリストとどう向き合うかというのはそれこそ自身の存在そのものをかけた全身全霊の戦いだったのである。そのことをぜひ強調したい。

『ヨブ記』自体はそれほど分量も多くなく、読みやすいお話なので興味のある方はぜひ読んでみてほしい。私にとっても「信仰とは何か」を考える上で非常に大きな指針を与えられた物語だ。

さて、ここからはドストエフスキー夫妻が夏を過ごしたヴヴェイの街を見ていくことにしよう。

ジュネーブからヴヴェイまでは鉄道でおよそ1時間弱。レマン湖のほとりに沿って鉄道は走る。

ヴヴェイに近づくと湖の対岸にまるで崖のような山がそびえ立つ。雲間から差し込む光も美しい。

ヴヴェイの駅に到着。こじんまりした駅舎。ここからドストエフスキーが住んだ家へ向かう。

駅の目の前の通りからすでにレマン湖が見える。街としてはかなりコンパクトにまとまっているようだ。

商店街、とまではいかないが両側にお店が立ち並ぶ通りを歩く。間もなくドストエフスキーの家に到着する。

こちらがドストエフスキー夫妻が失意の日々を過ごしていた家だ。彼らはこの建物の二階部分に住んでいた。

角度を変えて見てみよう。一階の壁にはジュネーブの時と同様、記念プレートがはめ込まれていた。

ヴヴェイの駅からはゆっくり歩いて15分もかからない距離だ。

家を出て真っすぐ向こう側に歩けばすぐにレマン湖が広がる。ドストエフスキー夫妻も気を紛らわせるためにこの道を通って二人で散歩に出かけていたことだろう。

さすがはスイスの誇る景勝地。湖沿いの遊歩道も綺麗に整備され、カフェやレストランが立ち並んでいる。

遊歩道を歩いていると開けた展望台のようなスペースがあり、そこにはなぜかフォークが湖面に突き刺さっていた。なんてシュールな光景だろう。だが不思議と違和感はない。

それにしても美しい・・・あの光り輝く山々を超えればまさに理想の国イタリアがある。ドイツ方面からイタリアへ入るにはこの山を通るのがかつて一般的だった。歴史上どれだけ多くの作家、芸術家がここから憧れの国イタリアへ向かったことだろう。

「あの光り輝くアルプスの山々を越えれば、そこは理想の国イタリアなのだ!」

こうしたイメージはまさに視覚的にもリアルなものなのだということがよくわかった。理想の芸術があの向こうにあるのだと自然に高揚してしまうのもわかる気がする。それほど素晴らしい景色だった。

だが、悲しみに沈むドストエフスキー夫妻にとっては、このような景色も少しも慰めとはならなかったことだろう。

私はこの湖を見ながら、ドストエフスキー夫妻のことを考えずにはいられなかった。

二人はジュネーブからここまで船に乗ってやって来た。そしてソーニャの死を悲しみながら、ドストエフスキーはアンナ夫人にこれまでの苦しかった日々を打ち明けた。『回想』ではこのことについてさらっと書かれていただけだったが、これは二人の関係性にとって極めて重大なことだったのではないだろうか。

夫妻はソーニャの死の悲しみと苦しみを共有した。そしてドストエフスキーは心のありったけをアンナ夫人に開いてみせた。悲しみ、苦しみが本当の意味で二人を結びつけた。ソーニャの誕生と死が彼らを決定的に結びつけたのではないだろうか。そういう愛もあるのだ。楽しく、情熱的に過ごすことだけが愛じゃない。二人で苦しみも分かち合い生きていく。そこに人生がある。

アンナ夫人の「わたしは、なんと悲しい人生だろうと不幸な夫に心から同情して、いっしょに涙を流さぬわけにはいかなかった。ともに分かちあったふかい悲しみと、痛ましい心の奥底をさらけだしてみせてくれた誠意のこもった話とは、ふたりをいっそうつよく結びつけるかのようだった。」という言葉はまさにそれを表していると思う。

バーデン・バーデンの地獄の日々を乗り越え、ジュネーブ、ヴヴェイで幸せと悲しみを共有した二人。

ドストエフスキーとアンナ夫人の結婚生活で、この時期が二人の関係性における決定的なものではないかと私は思う。

これから先の二人も相変わらずの苦労続きである。しかし何かが決定的に変わったのだ。ここから先の二人はまさに復活への道を突き進んでいく。二人がそれこそ一体となって作家業を営んでいくのだ。そして晩年の幸福な家庭生活への道筋が着実に形となっていくのである。

続く

主要参考図書はこちら↓

次の記事はこちら

前の記事はこちら

ドストエフスキーのおすすめ書籍一覧はこちら

「おすすめドストエフスキー伝記一覧」

「おすすめドストエフスキー解説書一覧」

「ドストエフスキーとキリスト教のおすすめ解説書一覧」

関連記事

コメント