トルストイの妻ソフィア夫人は本当に悪妻だったのか?トルストイ最後の家出について考える

トルストイの妻ソフィア夫人は本当に悪妻だったのか?トルストイ最後の家出について考える

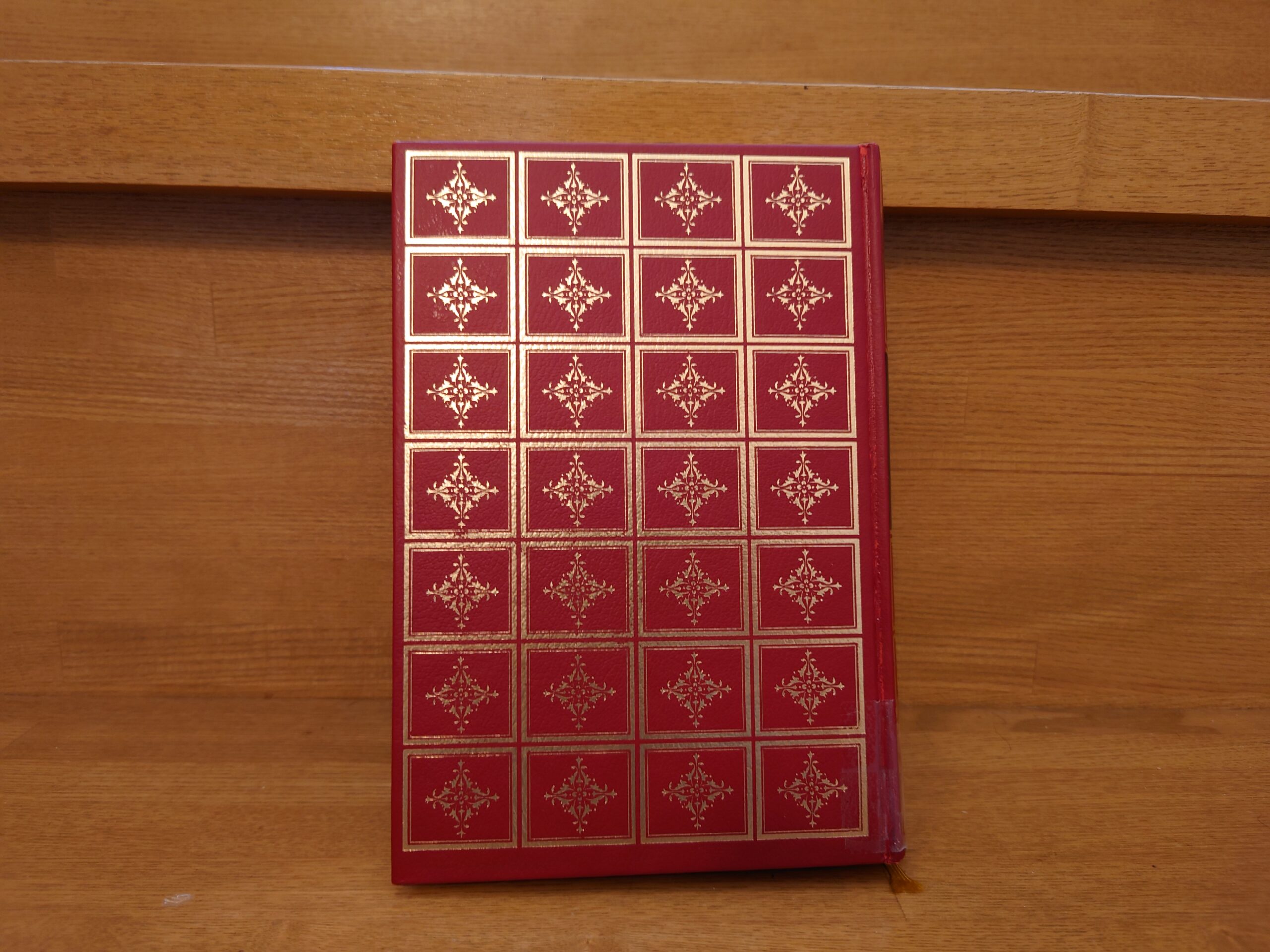

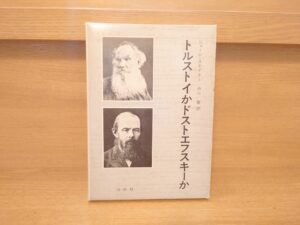

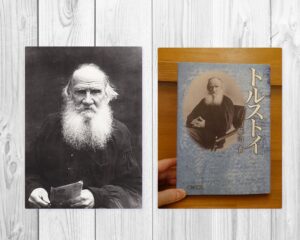

今回の記事では河出書房新社の『トルストイ全集19 妻への手紙(新訳)付き・回想』1979年初版を参考に「トルストイの妻ソフィア夫人は本当に悪妻だったのか?」というテーマで考えていきたいと思います。

トルストイの妻ソフィア夫人はよく「世界三大悪妻」のひとりとして紹介されることがあります。

その一例をご紹介します。

⚫︎トルストイの妻・ソフィア

「tenki.jp」 「世界三大悪妻って誰のこと⁉4月27日は悪妻の日」より

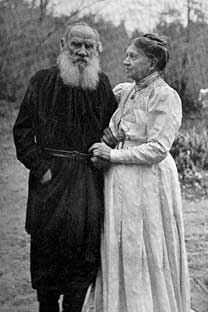

ロシアの偉大な文豪・トルストイの妻・ソフィア。子供たちを共に育てあげしっかり家庭を築いたトルストイとソフィア。何故、「悪妻」と呼ばれるようになったのでしょう。晩年、トルストイが文学から離れて、宗教活動などをするようになってからは、理想を求めるようになった夫と、現実的な生活をしたい妻の間で軋轢が生じるように。夫婦喧嘩が絶えなくなり、ついにトルストイは家出を。

その後、アスターポポという駅でトルストイは肺炎で亡くなったと言われています。財産を貧しい人に与えたいと理想に燃えたトルストイ。それに反し財産を守るため版権を取得するのに奔走したソフィア。そんな対立に耐えられなかったトルストイが家を出たと言われています。そんな晩年のいざこざが彼女が「悪妻」と呼ばれる要因になったようです。

通俗的にはこのようにソフィア夫人について書かれることが多いのですが、これまでトルストイ作品、伝記、参考書を読んできてやはり思うのは、「ソフィア夫人は本当に悪妻だったのか?トルストイの方にも原因があったのではないか?」ということです。

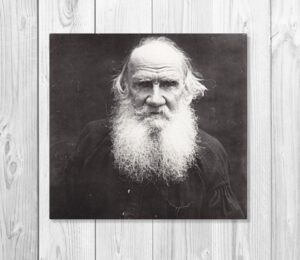

トルストイはあまりに偉大で、彼を崇拝する人は世界中にたくさんいました。

ですが、トルストイの語る理想や行動は素晴らしいものではありましたが、彼の晩年の家庭生活は悲惨なもので、最後は家出をしたまま亡くなるという悲劇的なものとなっています。

こうした悲劇の原因が主に妻のソフィア夫人に帰せられることが多いのですが、私は「はたして本当にそうなのだろうか」と疑問を持たざるをえませんでした。

こうした疑問について考える上で今回参考にしていくのが河出書房新社の『トルストイ全集19 妻への手紙(新訳)付き・回想』という作品になります。

ありがたいことに「トルストイ夫人は本当に悪妻だったのか」ということについてまさに解説してくれていたのがこの本だったのです。

では、早速この問題について書かれた箇所を読んでいきましょう。

彼女はトルストイ自身も認めていたように、夫と家族をこよなく愛し、夫の仕事に理解と協力を惜しまず、トルストイが手紙の中でもしばしば忠告しているように自己の体力をも顧みずに文字どおり献身的に家のために尽くした、いわゆる良妻賢母の典型ともいうべき婦人であったと言えるであろう。このことはこれから述べるトルストイ家の悲劇についてもこれを夫人を悪妻視する世上の通説で簡単に割り切らずに、読者個々の判断を仰ぎたいと思って、特に書き添えたのである。

河出書房新社、中村融、中村白葉訳『トルストイ全集19 妻への手紙(新訳)付き・回想』1979年初版P405-406

これから読んでいくのはこの本の訳者中村融氏による解説です。上で述べられているように、ソフィア夫人は悪妻どころか良妻賢母の典型というべき婦人だったのでした。

では引き続き見ていきましょう。

さて、トルストイの家庭生活については、前巻の解説の中でも少しふれたが、約二十年間は「善良で、愛すべき」このソフィヤ夫人を文字どおり最愛の伴侶として、愛児たちに囲まれ、自らはヤースナヤ・ポリャーナの大地主として、またすぐれた文学者として著述に没頭することが出来たわけだから、時に夫婦間に表面化した不一致があったとはいえ、また家庭内の平安も、秩序も、習慣も先祖からのそのままの古い形でつづいていたとはいえ、彼の家庭生活の幸福は、かつて青年時代に彼自身がコーカサス(カフカース)で空想していたところにほぼ近く保たれていたと言うべきであろう。

この平穏・幸福な家庭生活に亀裂が生じ、影がさすようになったのは、トルストイのいわゆる精神的転機以後のことであり、これをソ連版書簡集の解説者ローザノフの言葉をかりて説明すれば、「土地もなく、貧しく困窮のうちに賦役の生涯を終える農民たちの労力を無意識のうちに搾取し、彼らの勤労の上にそれを自らの特権として安住し、怠惰で、空虚で、飽満な生活をつづけてゆくことを今や自然に反する不道徳、つまり悪と悟った彼としては、もはや従前どおりに暮らしてゆくことは出来なくなった」のであり、自己のこのような生活を手紙の中でも、「恐ろしい、化膿した、悪臭を放つ傷口」にたとえている。

しかもそれだけにとどまらず、理想家であるトルストイは、自分のこの新たな「信仰」が同時にすべての近しい、親しい人々の「信仰」になってくれることを切望し、民衆の勤労に依存した、ぜいたくな地主貴族的な生活をすてて、つまり、土地も、財産も、特権もすべて放棄して、素朴で、勤労的な農民生活を始めてくれることを願ったのである。そして精神的には彼の家族も「暴力の法則」ではなしに「愛の法則」に拠って暮らし、「人々の愛の協同体」の一細胞となることを心から望んだのである。

河出書房新社、中村融、中村白葉訳『トルストイ全集19 妻への手紙(新訳)付き・回想』1979年初版P406

※一部改行しました

トルストイの精神的転換は徐々に進んでいたものの、『アンナ・カレーニナ』の完成後に特に顕著になります。

これまで当ブログでも彼の宗教的著作についてはいくつか紹介してきましたが、それらを読めばわかるように、その内容はかなり極端です。財産を全て放棄し、自分たちも農民たちと同じように生きる。これは大貴族として生きてきたトルストイ家の家族にとっては到底受け入れがたいものでした。

こうした潔癖とも言える理想に猛烈に突き進み、それを家族を含め身近な人にも求め始めたトルストイ。ここに家庭崩壊の端緒が現れてきます。

ソフィヤ夫人も子供たちも(ことに息子たちは)トルストイのこの「新しい信念」を認めることを拒み、従来から伝統的な地主制度の中で自分たちに与えられているすべての財産を守ろうとした。そしてここから破綻が始まったのである。

トルストイとしては民衆の側に立って新たに開眼したとはいえ、元来、道徳的自己完成を目ざして来た彼としては、自己の抱く無抵抗主義からも妻子に苦しみと悲しみをもたらすことは出来ず、この矛盾した哲学に自ら深刻に悩み苦しむ結果となった。これはあるいは彼の生涯における最大の苦悩の一つだったといっても過言ではないかもしれない。

八〇年代のはじめから、彼はこの袋小路からの突破口を懸命になって探し求め、一八八五年のチェルトコーフあての手紙でも、「私は迷っている。死にたい。家出しようとか、自分の地位を利用して生活全体をひっくり返してやろうという計画までが浮かぶ」と告白しているほどである。

夫人は夫のこの意向に対して正面から反対し、あくまで領地を保有してこれを子供たちに伝えようとすると共に、家族の生活に必要な収入をもたらす夫の文学的労作に対する権利を確保しようとした。一九一〇年の夏にトルストイから夫人に送られた手紙はこうした夫婦間の葛藤の深刻さをはっきり示している。

河出書房新社、中村融、中村白葉訳『トルストイ全集19 妻への手紙(新訳)付き・回想』1979年初版P406-407

※一部改行しました

そして次の箇所では「悪妻」とされてきたソフィア夫人が本当に悪妻だったのかということについて解説が続きます。

こうして遂に悲劇的な家出にまでトルストイを追いこんだこの夫婦間の「つんぼの壁」については、一般には夫人の頑なな性格と無理解のみがその唯一の原因としてあげられているようであるが、これは必ずしも正しい見方とは言えないように思われる。

というのも、ここにはこれに付随した幾つかの事情が潜在していたからである。まず第一に、夫を深く愛し、その仕事にも理解を示し、前述したように自らも出来る限りの協力を惜しまなかった半面、また家族にも「痛いほど」の愛情をもっていたソフィヤ夫人としては、この大家族の将来の生活を預る主婦として、母として、簡単に夫の「新たな信仰」に殉じることが出来なかったことは誰しも納得し得るところであろう。

第二に、彼女の健康が晩年には侵されて、たえず神経症におびやかされ、ひどいヒステリックな状態にあったことも考慮されなければなるまい(妻の健康に対する異常なまでのトルストイの心配は、本巻の読者は随所に見出されるであろう)。

第三に、トルストイとチェルトコーフとの深い親交に対する夫人の強い抵抗も、一般にはこれを女性らしい嫉妬と見なしているが、これもそう簡単に片づけられていいものかどうか。元来、私的なものであるべき夫の日記が妻の自分ではなく、この親友のもとに保管されていたことなども夫人としては耐えがたいことだったにちがいなく、またいかに高弟であり、トルストイから深い信頼を寄せられていたとはいえ、本来立ち入るべからざる他人の家庭内の問題に無神経に、しかも執拗に干渉し、夫人の行動のすべてをただ「虚偽」とのみ見なし、彼女のあらゆる希望や懇願をことごとく病的なわがままと断じて、夫人にとって重要な関心事(例えば夫の日記を返還してほしいとか、遺言状の作成とか)に対しても徹底して反対していたチェルトコーフの態度も改めて指摘されなければならないであろう(これに対してはさすがにトルストイさえも「妻は実際病気なのだから……」とチェルトコーフに弁明しなければならないほどだった)。

河出書房新社、中村融、中村白葉訳『トルストイ全集19 妻への手紙(新訳)付き・回想』1979年初版P407ー408

※一部改行しました

いかがでしょうか。こうした背景が見えてくると、ソフィア夫人に対する見方が変わってきますよね。

ソフィア夫人はトルストイの作家活動を献身的にサポートし、大家族を切り盛りしていました。

しかしそうした生活をトルストイがいきなり「そんなものは全て虚偽だ。人間は真実に生きなければいけない」と全てバッサリと切り捨てようとしたのです。これはいくら何でも厳しすぎます。

そして次の箇所ではさらに驚きの事実が語られます。

さらにそれに加えて家族、近しい人々、親友、そしてひろくヤースナヤ・ポリャーナの住人たちの間には、この作家の生涯の数か月には互いに反目する二つのグループが出来ていて、ひたすら平安を渇望するこの老作家をも容赦せずに、抗争をつづけていたといわれている。

邸の内外をとりまくこうした雰囲気が、遺言状作成後に一そう灼熱したことは想像に難くないところで、この遺言状によって夫人と家族はトルストイの著作出版からの収入を利用する権利を奪われることになったわけだが、一方、家族に秘して作成されたこれが彼らの側からすれば、嫉妬ぶかい嫌疑、歪められた噂、陰謀、声なき不満の原因となったのもまた当然のことであった。

トルストイは自己の周囲に渦巻くこうした幾つかの事情にすっかり疲れ果ててしまい、チェルトコーフに対して、「私は自分のからだが左右に引き裂かれてゆくのを感じる」と悲痛な叫びをあげているほどだった。

そして一九一〇年十月二十八日払暁のあの悲劇的な彼の家出はすべてこうしたことのやむを得ない結末として行なわれたのである。

他人の家庭生活、ことに夫婦生活には第三者の窺い知るべからざる多くの事情が常に伏在しているもので、軽々にこれを断じることは厳に慎しまなければならないと思われる。ことにトルストイの場合には彼が世界的に高名な作家であっただけにこの最後の不幸をもたらした下手人としてともすれば夫人が割のわるい役を負わせられがちだが、公平に言って、彼に彼なりの理由があったとすれば、同じく夫人の側にもそれだけの理由を認めるべきであり、ことに人一倍夫や家族を深く愛していたソフィヤ夫人の場合には一そうこのことが強凋されてもいいのではなかろうか。

だからここではただ家出が夫妻のいずれの側にとっても悲劇であった、という形容だけにとどめておきたいと思う(夫の家出を知った直後に夫人が邸内の池に入水自殺をはかったことも周知の事実である)。

河出書房新社、中村融、中村白葉訳『トルストイ全集19 妻への手紙(新訳)付き・回想』1979年初版P407ー408

※一部改行しました

先の引用でも側近のチェルトコーフの行動が語られていましたが、トルストイの周囲ではさらに大きな規模で不幸な衝突が続いていたのでした。

私はこの箇所を読んでいてとても悲しくなりました。

愛、平和、非暴力の教えを説いていたトルストイの晩年はこんな有り様だったのです。

このような状況ではトルストイが絶望してしまうのも無理はないように思ってしまいました・・・

トルストイは「トルストイ主義」の預言者であり、数え切れない人から崇拝されていました。

しかし崇拝されればされるほど、トルストイ自身の理想からかけ離れた状況になっていく・・・

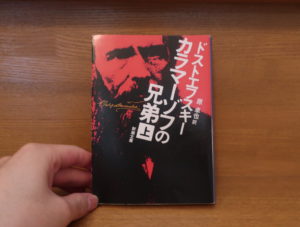

宗教的カリスマ、預言者になることの恐ろしさはまさに、あのドストエフスキーの『カラマーゾフの兄弟』に出てくる大審問官を連想してしまいます。

トルストイの絶望、家庭崩壊はソフィア夫人が悪妻だったからだという単純な理由では語ることはできません。

さらに、訳者が述べていたように家庭内の問題でもあるので全てが明らかになるということもないでしょう。

ですが、「ソフィア夫人は本当に悪妻だったのか」という問いに対しては「否」と答えることはできるのではないかと思います。

トルストイ晩年の姿を思うと私はいつも悲しくなります。

若い時から苦しみ続け、最晩年にようやく幸福な生活を過ごすことができたドストエフスキーとは驚くほど対称的です。

2人の生涯とその作品、思想は本当に興味深いです。

今回「ソフィア夫人は本当に悪妻だったのか」というテーマで考えてきましたが、私にとっても非常に貴重な学びになりました。

以上、「トルストイの妻ソフィア夫人は本当に悪妻だったのか?トルストイ最後の家出について考える」でした。

Amazon商品ページはこちら↓

前の記事はこちら

関連記事

コメント