ジイド『ドストエフスキー』あらすじと感想~ノーベル賞フランス人作家による刺激的なおすすめドストエフスキー論

ドストエフスキー論の古典!アンドレ・ジイド『ドストエフスキー』概要と感想

アンドレ・ジイド(1869-1951)Wikipediaより

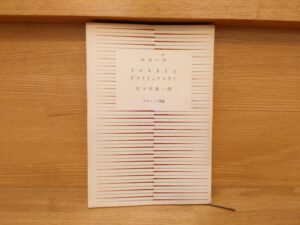

今回ご紹介するアンドレ・ジイドの『ドストエフスキー』は1923年に出版され、ドストエフスキー論の古典として知られている作品です。

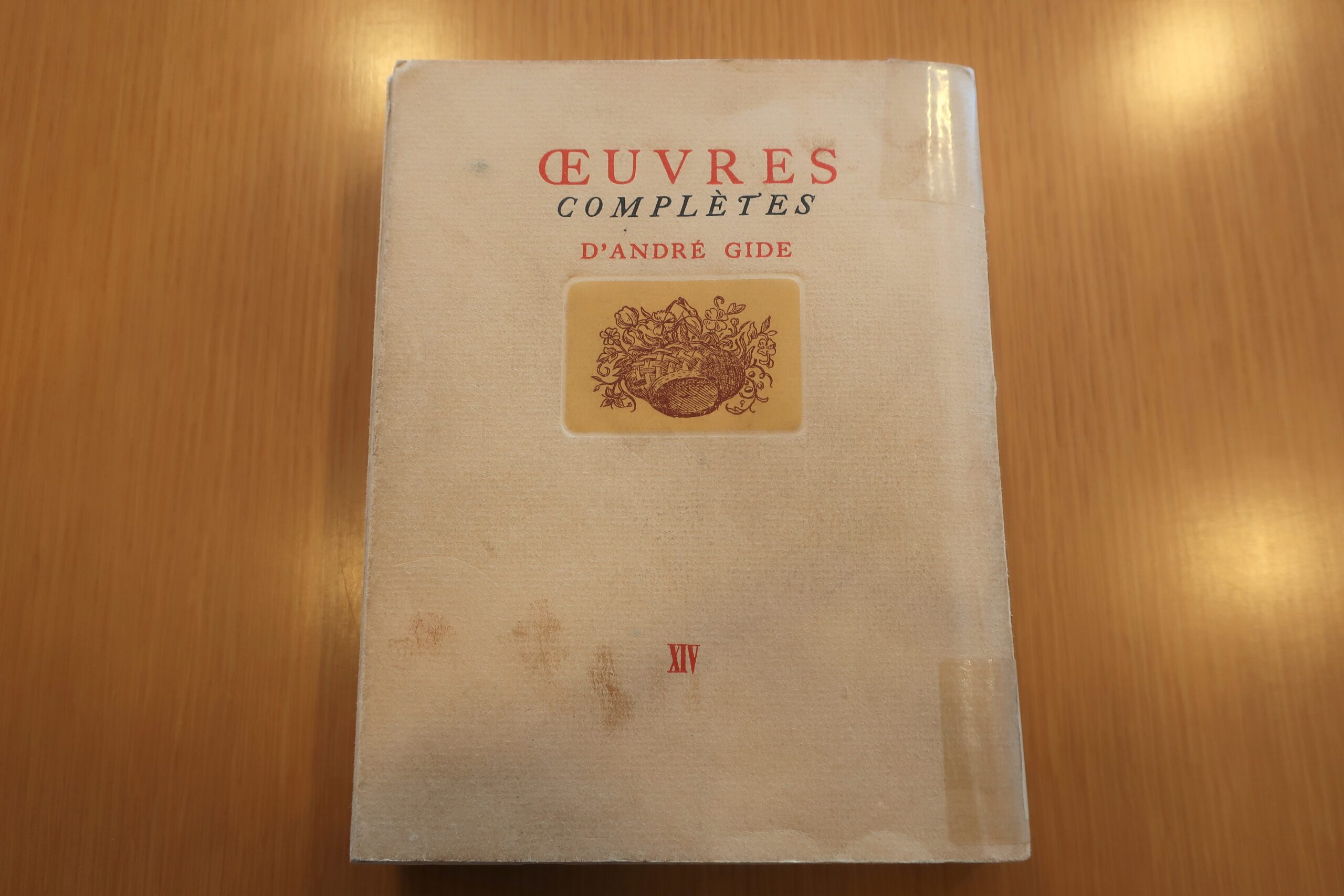

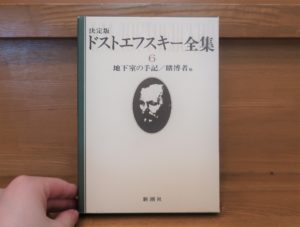

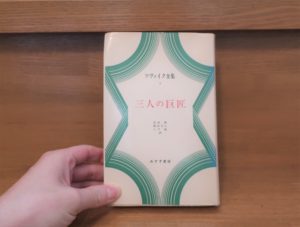

私が読んだのは新潮社版、『ジイド全集第14巻』所収、寺田透訳の『ドストエフスキー』です。

前回の記事「ジイド『ソヴェト旅行記』~フランス人ノーベル賞文学者が憧れのソ連の実態に気づいた瞬間」でジイドが1936年に憧れのソ連に旅をするも、大きな幻滅を味わったことをお話しました。

ジイドの『ドストエフスキー』はいつか読みたい本だなとずっと思っていたのですが、『ソヴェト旅行記』がとても面白かったのでこの機会にいざ読んでみようと私は図書館へ向かったのでした。

『ソヴェト旅行記』と同じく新潮社版のジイド全集は旧字体で書かれているので一瞬面を食らうのですが、読み始めてみるととジイドの筆が素晴らしいのかとても読みやすいものとなっていました。

そして何より、ドストエフスキーに対する興味深い見解がいくつもあり、目から鱗と言いますか、思わず声が出てしまうほどの発見がいくつもありました。今まで疑問に思っていたことや、かゆいけど手が届かなかった微妙なところをとてもわかりやすく解説してくれます。

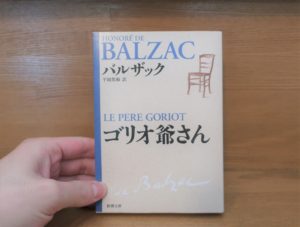

フランス人作家ということでバルザックなどフランス文学との対比によってドストエフスキーを語ってくれるのも非常にありがたかったです。

とにかく明瞭でわかりやすい!これが読んでみての率直な感想です。

ぜひとも紹介したい箇所がたくさんあるのですがあくまでこの記事はドストエフスキーの参考書の紹介です。

全てをお伝えすることができませんが、この本の雰囲気を伝えるためにもいくつか引用したいと思います。

バルザックとの対比ー理性の放擲、ドストエフスキーは仏教的?アジア的?

バルザックと対比しながら、ドストエフスキーがわれわれに示す固い決意の人間を調べるとき、私は、彼らがひとり残らず恐るべき存在であるのに卒然として気がつきます。

名簿の筆頭にあるラスコリニコフを御覽なさい。これは最初のうちひよわい野心家で、ナポレオンたらんと望みながら、質草をとって金を貸すのが商売の女と罪のない娘を殺すことがようやくできるだけです。スタヴロギン、ピョートル・ステパノウィッチ、イワン・カラマゾフ、『未成年』の主人公をご覧なさい。(中略)

彼の主人公たちの意志は、彼らにうちに存する彼らの知性と意志すべては、彼らを地獄に向けて突き落すように思われます。そして私は、ドストエフスキーの小説のなかで、知性がいかなる役割を演じているかを求めてみると、それはつねに悪魔的な役割であることに気づくのです。

彼の作中人物のうちでもっとも危険なものは、またもっとも知的な作中人物でもあるのです。

さらに私は、ただドストエフスキーの作中人物の意志と知性は、悪のためにのみ行使されると言うだけではなく、それらが善をめざして全力を揮う場合ですら、それらの到達する徳は、自尊心の強い、破滅にみちびく徳だと言うものであります。

ドストエフスキーの主人公たちは、彼らの知性を断念し、彼らの個人的意志を放擲することによってのみ、自我の放棄によってのみ、神の天国に入るのです。

たしかに、ある程度では、バルザックもまたキリスト教的作者だということができます。けれども二つの倫理学、すなわちこのロシヤの小説家の倫理学とこのフランスの小説家のそれを対決させることによってこそ、われわれは、後者のカトリーク信仰と、もう一方の小説家の純粋に福音書的な教義とはどれほど遠ざかっているものか、カトリークの精神はただキリスト教的であるだけの精神とどれほど相違しうるものかを理解できるのであります。

ひとの気にさからうようなことはしたくありませんので、皆さんがこの方がよいとおっしゃるなら、こう申しましょう。

バルザックの『人間喜劇』は福音書とラテン精神の接触から生れたものであり、ドストエフスキーのロシヤ劇は福音書と仏教、アジヤ的精神から生れたものである、と。

新潮社版、『ジイド全集第14巻』所収、寺田透訳『ドストエフスキー』P96-97

※一部改行し、旧字体を新字体に改めました

この引用の最後の部分は私もかなり驚きました。

ドストエフスキーは仏教的でさえあるとジイドは言うのです。

ジイドが仏教をどのように捉えているかはわかりませんが、おそらく西洋の理性・自我信仰に対し、ドストエフスキーの「彼らの知性を断念し、彼らの個人的意志を放擲することによってのみ、自我の放棄によってのみ、神の天国に入る」という思想がヒントになっていると思われます。それと、ロシアがアジア的な国であるというのも大きなポイントであると思います。

ジイドのこの指摘は非常に興味深いので今後も忘れずにいたいと思います。

ドストエフスキーが西欧社会を批判していたことについては以下の記事でも紹介していますので興味のある方はご参照ください。

「ドストエフスキーは思想家としてはそこまでの存在ではない」の本意

「ドストエフスキーは思想家としてはそこまでの存在ではない」

私はかつてどこで読んだかは忘れてしまったのですが、そのようにドストエフスキーを評する言葉を読んだことを覚えています。

私はそれを読んで「ずいぶんなことを言うものだなあ。何でそう思うんだろう」と疑問に思ったものでした。

その言葉を述べた方がジイドの『ドストエフスキー』を読んだのかどうかはわかりませんが、まさにこの本にそのことに言及する箇所があったのでぜひここで紹介したいと思います。全てを引用するとかなり長いものになってしまうのでその一部を抜粋します。

われわれが彼に期待しうるもっとも深遠な、もっとも稀有な真理は、心理の領域に属するものです。そしてさらに附け加えるならば、この領域において彼の提起した観念は、ほとんどつねに問題の状態に、疑問の状態にとどまっています。彼は解答よりむしろ開陳を求めているのですーまさしく、極度に複雑で、混り合い、相交っているがゆえに、ほとんどつねに混沌とした状態をつづけているかかる疑問の開陳を、です。

要するに一言で言ってしまえば、ドストエフスキーは本来の言い方では、思想家とは言えないのです。小説家なのです。

新潮社版、『ジイド全集第14巻』所収、寺田透訳『ドストエフスキー』P98-99

※一部改行し、旧字体を新字体に改めました

そもそも「思想家」とは何かと考えた時、ただシンプルに「思想を考えている人」とすれば、たしかにドストエフスキーも思想家です。

しかし、思想家の定義を「ある抽象的な思想を体系的にまとめ、人々に対して普遍的な答えを提供する人」とするならばこれはドストエフスキーとはだいぶ違ったことになってきます。

ドストエフスキーはジイドが言うように「人々に答えを与える」より、「問いを突き付け、世界の複雑さを開陳する」人間だからです。

彼の観念はほとんど絶対的であるためしがないのです。ほとんどつねに、その観念を言葉に出して言う人物と相対的なのです。

さらにそれ以上に私はこう言いたいのですが、ただそれらの人物に相対的なばかりでなく、それらの人物の生涯のちょうどある瞬間に相対的なのです。それらの観念は、いわばこれらの人物の特殊な、又瞬間的な状態によって≪得られる≫のです。

新潮社版、『ジイド全集第14巻』所収、寺田透訳『ドストエフスキー』P100

※一部改行し、旧字体を新字体に改めました

ドストエフスキーは私たちの肉体を離れた抽象的な観念ではなく、あくまで人間一人一人の、そしてある瞬間の実際の生活における思考や心理を描くのです。抽象的な思想を云々するのではなく、あくまで血肉を具えた人間を彼は描くのです。人類すべてにあてはまる抽象的で普遍的な「絶対的な思想」を説かない、いや求めないところに彼が「思想家」としてではなく「小説家」としての天分があるとジイドは述べるのではないでしょうか。

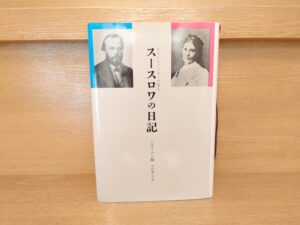

ドストエフスキーがどれほどまでに≪小説家≫であるか、それを『ある作家の日記』はわれわれに示してくれましょう。なぜかというと、彼は理論的な、又批評的な論文においては随分凡庸ですが、何かの人物が舞台面に入るやたちまち素晴しくなるからです。

実際この日記のなかにわれわれは『農奴マレイ』という美しい物語、および取りわけ、ドストエフスキーの作品中でもっとも力強いものの一つである讃歎すべき『クローツカヤ』、これは彼が大体同じ時期に書いた『地下室生活者』の独白と同じように、本来の言い方をすれば、長い独白に他ならぬ一種の小説なのですが、こういうものを見出せるのです。(中略)

われわれは同じ書物の他の個所で、彼が百歳になる老婆に出会ったときの物語を読むことができます。彼はその老婆が腰掛けに坐ったまま町を通って行くところを見ます。彼は老婆と話をし、それから先へ行きます。

けれども彼は夕方、「自分の仕事を終えてから」、この老婆のことを又考えます。老婆が自分の家の身内のものたちのところへ帰ったところ、身内のものたちの老婆に対する言葉を想像します。彼はこの老婆の死を物語ります。「私は話の終りを想像するのが楽しい。そればかりでなく私は小説家だ。いろいろな話をするのが好きなのだ。」

新潮社版、『ジイド全集第14巻』所収、寺田透訳『ドストエフスキー』P100-102

※一部改行し、旧字体を新字体に改めました

この箇所を読んで私は「ああ!なるほど!」とすごく腑に落ちる感覚を得ることができました。たしかに『作家の日記』はドストエフスキーが普段からどのようなことに関心を持っていたかを知るにはうってつけの作品です。

ドストエフスキーが自らを小説家であると言う理由もこのジイドの解説によってとてもすっきりしました。この記事では分量の関係で紹介できませんでしたが、ジイドはいくつも例を挙げてわかりやすく解説してくれます。興味のある方はぜひこの本を読んで頂きたいと思います。

ドストエフスキーは私たちの「世界の見え方」を一変させる

最後にもう一つだけ紹介していきます。ドストエフスキーの何がすごいのかを端的に表した箇所です。

われわれは広く認められた所与の上に立って生きておりまして、世界を、それが真実かくあるように見るよりむしろ、ひとがわれわれに言ったように、世界はこういうものだとひとから説得されたように見るあの習わしをたちまち身につけます。

いかに多くの病気が、それを報らされなかったうちは、全く存在しないように見えたことでしょう。いかに多くの奇怪な、病理学的な、変態的な状態を、われわれはドストエフスキーの作品を読んだがために教示されて、われわれの周囲に、あるいはわれわれのうちに認知することでしょう。

そうです、本当に、ドストエフスキーはわれわれの眼を、恐らくは珍しくもないものなのだがーただわれわれが見てとる術を知らなかったある種の現象に対して開かせるのだと、私は思います。

ほとんどひとりびとりの人間存在が示している複雑さに面して、視線はおのづから、またほとんど無意識に、単純化をめざします。

そういうのが、フランスの小説家の本能的努力です。フランスの小説家は、性格から主要な興件をとり出し、一つの相貌のなかに明確な線を見分け、それによって描き出される切れ目のない図形を人前に示すことに智慧を絞ります。バルザックであろうと、その他何がしくれであろうと、様式化の願望、要求が先に立ちます……

新潮社版、『ジイド全集第14巻』所収、寺田透訳『ドストエフスキー』P117

※一部改行し、旧字体を新字体に改めました

これまた素晴らしい解説です。

「私たちは世界をありのままに見ているのではなく、人から教わった見方を通して世界を見ているに過ぎない。そのため見えていなかったものが世界にはある。しかし人はそのことに気付かないのだ」とジイドは述べます。

ですがドストエフスキーはそれまで見えていなかった世界を見る眼を与えてくれます。

バルザックをはじめとしたフランス文学の特徴と比較してみるとそれがよりはっきりします。フランス文学のものの見方は複雑な世界を分析し、様式化、単純化して把握しようとします。

それに対しドストエフスキーは意識してのぞき込まなければ知ることのない世界の複雑さ、人間の心の混沌をそのままに見る眼を私たちに与えます。

ドストエフスキーを読めば私たちの世界の見え方が変わってしまう。

そういうことが実際に起こりうるのがドストエフスキーのすごいところだというのは私もとても頷けました。私自身も初めて読んだドストエフスキー作品『カラマーゾフの兄弟』でかなりのショックを受けてしまい、それ以降私の宗教観や人間観はそれに大きな影響を受けています。

おわりに

ここまでジイドの『ドストエフスキー』についてお話ししてきましたが、まだまだ紹介したいことがたくさんありますが記事の分量上、そうもいきません。

この本は本当にすごいです。出版は1923年ということで、ドストエフスキー論の古典として有名な本ですがその内容は全く古びていません。

ただ、本そのものがかなり古いので文字が旧字体であったり、なかなか手に入りにくい本であることが玉に瑕です。函館図書館にこの本があったからいいものの、そうでなければ私は読んでいなかったかもしれません。この本が復刻版として新たに出版される日が来ること願っております。(私は図書館で借りた後に、あまりに面白かったので中古で購入しました)

この本と出会えて本当によかったなと思います。これはかなりおすすめです。ものすごく興味深い内容が満載です。ぜひ手に取って頂けたらと思います。

以上、「ジイド『ドストエフスキー』ノーベル賞フランス人作家による刺激的なおすすめドストエフスキー論」でした。

Amazon商品ページはこちら↓

関連記事

コメント