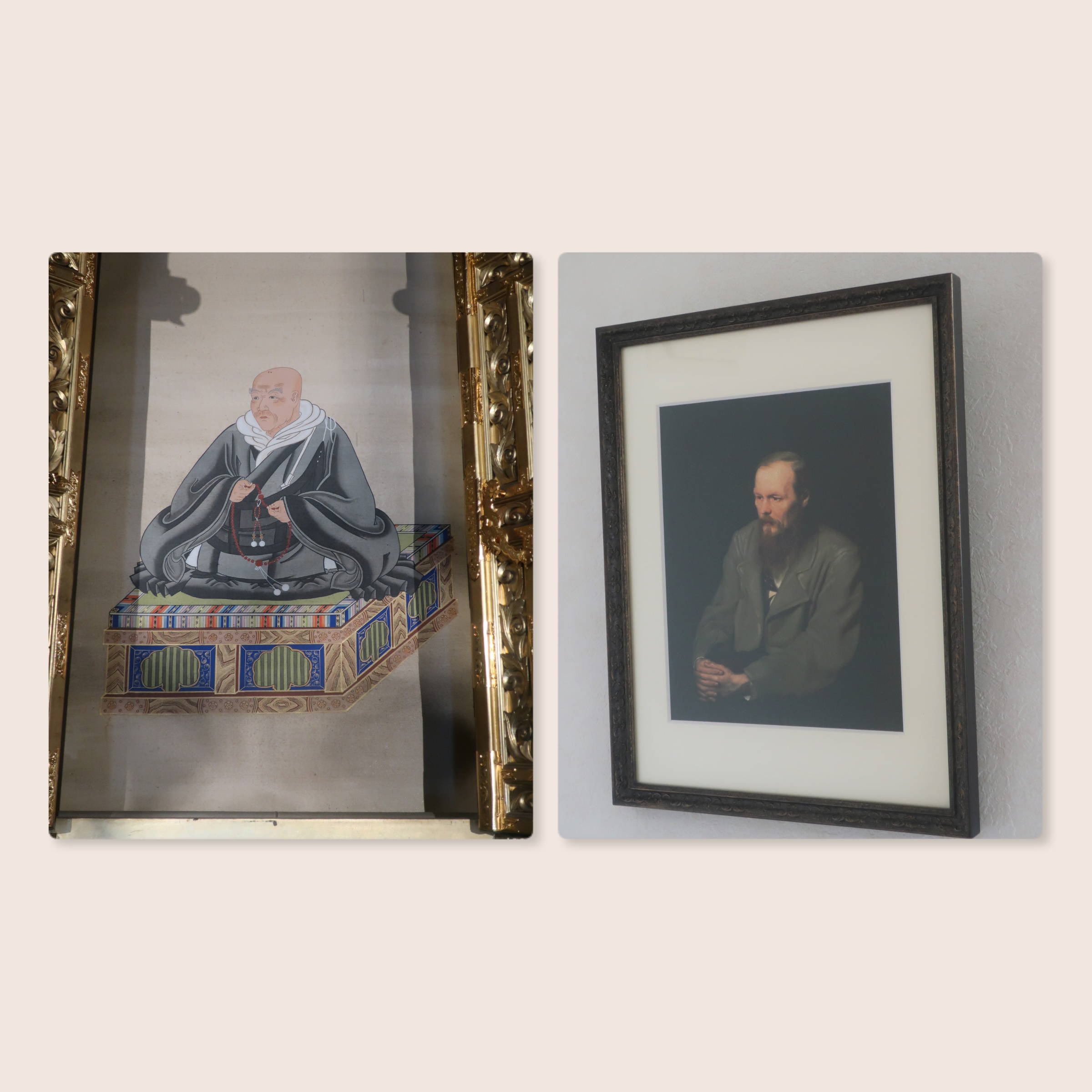

親鸞とドストエフスキーの驚くべき共通点~越後流罪とシベリア流刑

親鸞とドストエフスキーの驚くべき3つの共通点

親鸞とドストエフスキー。

平安末期から鎌倉時代に生きた僧侶と、片や19世紀ロシアを代表する文豪。

この全く共通点のなさそうな2人が実はものすごく似ているとしたら、皆さんはどう思われるでしょうか。

と、いうわけで、今回は親鸞とドストエフスキーの共通点についてざっくりとお話ししていきたいと思います。

共通点① 若かりし頃に政治犯として流罪判決を受ける

親鸞もドストエフスキーも若かりし頃、政治犯として流罪判決を受け、親鸞は京都から越後へ、ドストエフスキーはサンクトペテルブルクからシベリアへ送られていきました。

1207年、親鸞35歳の年、親鸞は師匠の法然の下で研鑽を積んでいましたが、法然教団は弾圧の憂き目に遭うことになりました。

元々法然の念仏思想は既存の仏教教団から、世の秩序を乱すものであるという非難を受けていました。「全ての人が念仏を称えれば救われる」という法然の思想は当時の社会事情から言えばあまりに危険な思想だったのです。

また、既存仏教側は法然にこう反論します。「念仏を称えるだけで救われるのならば、我々の行う修行の意味は何なのだ。我々の仏道は無意味だとでもいうのか。念仏をすれば救われるなど何の根拠もない。修行こそ仏教の基本ではないか」と。

法然教団は政治上の危険だけではなく、思想上の問題でも危険だと考えられていたのです。

ほんの小さな火花でも命取りになりかねない、そんな一触即発の綱渡り状態の中、終に事件は起こってしまいました。

ある日、後鳥羽上皇お気に入りの女官が無断で法然門下に合流したことに上皇は激怒。

それがきっかけで法然教団は弾圧され、女官の合流に関わった4人の門下が死刑、法然は責任を問われ僧侶の資格を奪われ土佐の国に流刑となり、教団の筆頭格の一人として親鸞も同じように越後の国に流刑の目に遭うことにありました。

さて、続いてドストエフスキーを見て参りましょう。

ドストエフスキーは1846年、25歳で文壇に華々しくデビューするも、その後は鳴かず飛ばず。次第にドストエフスキーは絶望していき、いつしか彼は当時禁じられていた社会主義思想サークルに出入りするようになっていきます。

当時のロシアは皇帝が国を統治するという社会形態でした。

ドストエフスキーが出入りするようになった社会主義思想サークルでは、農奴制の廃止や検閲の廃止、労働者の権利の改善などを論じ合っていました。

皇帝が強力な権限を持つ当時のロシアにおいて、その体制を転覆しようとする社会主義思想は弾圧の対象です。

1849年、ドストエフスキーの属するこのサークルはテロ行為を画策したとして摘発されます。実際にテロを行おうとしていたかについてはドストエフスキー自身は否定していますが、有罪判決は覆りませんでした。

半年の拘留期間の後、ドストエフスキーは12月の24日、シベリアへ向けて護送されました。マイナス40度にもなる極寒の地シベリアへと彼は向かって行ったのです。

共通点② 流罪生活での民衆との出会い

親鸞は越後の地で流罪生活を送りました。

親鸞は9歳の頃より比叡山延暦寺での生活を始め、29歳で山を下りてからも京都の街中で生活していました。

法然教団の下には貴族から庶民まで様々な身分の人々が集まっていたと言われています。

貴族は言わずもがなですが庶民でさえ、そこは日本の都京都です。文化水準は地方と比べれば高い水準のものだったことでしょう。

そんな人々と関わり合っていた親鸞がいきなり極寒の越後へと流罪に処されます。

そこで触れ合うことになった人々を見て、田舎ということをわかっていたとはいえ親鸞は大きな衝撃を受けることになります。

文字も読めず、都の文化も全く通じない田舎の人々。おそらく言葉もかなり違ったことでしょう。会話すらままならなかったかもしれません。

しかし、まさしくそのような人々との関わりから親鸞は自らの思想を深めていくのです。

親鸞は後にこのような和讃(※和歌のようなもの)を残しています。

「よしあしの文字をもしらぬひとはみな

まことのこころなりけるを

善悪の字しりがおは

おおそらごとのかたちなり」(正像末和讃より)

この和讃のポイントは「よしあしの文字をしらぬひと」はひらがなで書いているのに対し、「善悪の字しりがおは」の方は漢字で書いている点にあります。

親鸞はわざとひらがなと漢字を書き分けています。

なぜでしょうか?

それは田舎の人々、下層の人々は文字の読み書きも出来なければ、都の文化も哲学も何もないからです。しかし、それでも人々はいのちを慈しむ「まことのこころ」を知っているのです。

それに対し都の人々は自らの知識や行いを誇り、善悪の観念を振りかざし互いに争っている。善悪の文字は知っていても、それは「おおそらごと」に過ぎないと親鸞は悟るのです。

親鸞は法然から学んだ思想を田舎の生活でより深化させていくことになりました。その思想の深まりが主著の『教行信証』へと繋がっていくのです。

さて、続いてドストエフスキーを見て参りましょう。

ドストエフスキーは4年間、シベリアのオムスク監獄に服役します。

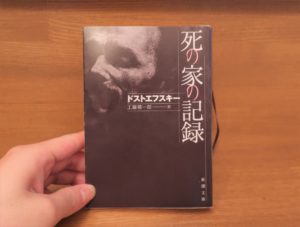

その時の経験をドストエフスキーは流罪から復帰後に『死の家の記録』という小説に著しています。※あらすじ等は下の記事をどうぞ

この作品はドストエフスキー作品の中でも珍しく内面の葛藤が描かれた思想的作品というよりも、写実的に描かれた作品で、まるで映画を見ているかのようにすらすら読めます。

あのトルストイも大絶賛し、この作品によってドストエフスキーは文壇での評価を再び獲得することになります。

ドストエフスキー作品においておそらく最も読みやすく、また最も面白く読める作品ではないかと思われます。ドストエフスキーを初めて読むならまずこの作品がおすすめです。

さて、監獄に収容された人間はありとあらゆる罪を犯した罪人です。

都会で暮らしていたドストエフスキーが初めて見るような人間ばかりで、そのあまりに過酷な環境と相まって非常に大きな衝撃を受けることになります。

しかし、そんな囚人達との共同生活の中でドストエフスキーは人間の根源とは何かを彼らを観察しながら思索していきます。

ドストエフスキー自身もこの監獄生活において得たものこそ、後の作家生活において多大な影響を占めていると認めています。

「民衆の中にこそ最も大切なものがある。」

ドストエフスキーは流罪生活における民衆との出会いによってそれを悟るのでした。

共通点③ 徹底した自己内省。思想の鬼。

親鸞は元々比叡山延暦寺で修行していた僧侶であることは先に述べました。

しかし、29歳で山を下り、法然の念仏思想に傾倒します。

そして流罪を経て90歳で亡くなるまでその思想は深まり続け、亡くなるぎりぎりまで執筆活動を続けていました。最も多作だった時代が75歳を超えた晩年からという超人的なはたらきぶりです。

親鸞は自らの心をとにかく深く深く凝視していきます。

本当に仏を信じるということはどういうことなのか。私の心にほんの一片の煩悩も混じらぬ祈りはありえるのだろうか。

親鸞はとことん突き詰めていきます。親鸞は妥協を許しません。

熱烈に、そして命をかけて仏の救いを求めたからこそ、「真の仏道、真の信仰とは何か」を探し求めずにはいられなかったのです。

『教行信証』には膨大な数の引用がなされています。驚くべきことにこの分厚い著作のほぼすべてが親鸞に先立つインドや中国、日本の高僧の著作で占められています。親鸞自身の思想を述べた箇所は割合から言うとほとんどありません。

親鸞は自らの思想を勝手に作り上げたのではありません。これまでの偉大な先達の思想を学び、そこから自らの心の中で思索し分析し、そして生活の中で実験しながら自らの思想を深めていったのです。

「宗教といえば、信ずることである」

と私たちは考えてしまいがちです。

しかし、親鸞は信じたいからこそ、熱烈に救いを求めたからこそ、疑い続けた人なのです。

本当にそれでいいのか、本当に私は救われる人間なのか、仏の救いはどこにあるのだろうか。

親鸞の悲痛な叫びは『教行信証』だけではなく多くの書物の中に見ることができます。

親鸞にとっては「疑いのない信仰はありえない」ものなのです。ここに親鸞思想の特徴があると私は考えています。

ドストエフスキーもまさしく、熱烈に神を求めたからこそ、絶望的な懐疑を経験します。以前の記事で述べた「大審問官の章」もドストエフスキーが信仰とは何かを極限のところまで自らに問い、内省していたからこそ生まれた物語であります。

ドストエフスキーは生涯、旧約聖書の『ヨブ記』の問題を心に抱えていました。

なぜ善良な人間にも災厄が訪れるのか。なぜ善良な人間の祈りが神に聞き届けられないのか。なぜこの世には悪がはびこり、何の罪もない人々が涙を流さなければならないのか。それでも私たちは神を信じ続けなければならないのだろうか。

これらが『ヨブ記』の主題です。

ドストエフスキーの信仰の原点はここにあると言われています。

親鸞、ドストエフスキーは共に徹底的な自己内省により、心の奥底へと潜っていきます。

この壮絶なる思想の戦いを経た2人こそ、思想の鬼と呼ぶにふさわしいのではないでしょうか。

まとめ

今回の記事では親鸞とドストエフスキーの共通点についてお話ししてきました。

若き日の流罪判決、民衆との出会い、そして徹底した自己内省。

この3つが大きな共通点であると私は考えます。

そしてドストエフスキーを知れば知るほど、その思想は親鸞と共通するものが多いと私は感じるようになってきています。

次の記事では今後のドストエフスキー研究の記事についてお話ししていきます。

本日も最後までお付き合い頂きありがとうございました。

続く

次の記事はこちら

前の記事はこちら

関連記事

コメント