アーレントの「悪の陳腐さ」は免罪符になりうるのか~権力の歯車ならば罪は許される?ジェノサイドを考える

アーレントの「悪の陳腐さ」は免罪符になりうるのか~大量の共犯者がいれば罪は許される?ジェノサイドを考える

これまで、当ブログではスレブレニツァの虐殺を題材にした映画『アイダよ、何処へ?』をきっかけにボスニア紛争やルワンダジェノサイドについてお話ししてきました。

その中でもルワンダのジェノサイドについて書かれた『隣人が殺人者に変わる時 ルワンダ・ジェノサイドの証言 加害者編』の次の言葉を読んだ時、私は思うことがありました。

被害者たちが体と心に大きな傷を負い、ジェノサイド後もなかなか立ち上がれず沈黙を続けなければならなかったのに対し、加害者たちは前向きに自分の将来を考えて早く反省し、早く被害者の赦しを得て、早く元の生活に戻ろうとした。そして彼らは殺人を続けた理由を問われると、「ラジオ放送(マスコミ)に踊らされたから」とか「命令されたから」とか「仲間はずれになるのが恐かったから」とか「略奪で生活が楽になったから」というようなことを述べている。生き地獄を体験し、身内も財産も社会に対する信頼も奪われた生存者の証言と比べて、殺人者の告白はあまりにも軽い。それは自らの心の破壊を食い止めるために、そしてあくまでも普通の人でありたいがために、自分たちの犯した行為を軽く考えるようなったからではないだろうかと著者は述べている。

さらに殺人者たちは、フツとツチの二者間の過去の歴史や時代の流れで、また権力を振りかざす政治家や元宗主国の思惑で、どうすることもできずに「仕向けられた」と言い、「やらされたのだから仕方がない。だから早く反省してやり直したい」と言う。とても利己的で、生存者のことがニの次になってしまっているのは明らかだ。

かもがわ出版、ジャン・ハッツフェルド著、服部欧右訳『隣人が殺人者に変わる時 加害者編』P325

「生き地獄を体験し、身内も財産も社会に対する信頼も奪われた生存者の証言と比べて、殺人者の告白はあまりにも軽い」という訳者の言葉は私にとっても非常に印象深いものでした。私もまさしくこの本を読みながらそれを強く感じました。

この本を通して私が感じたのは「赦し」とは何なのかということでした。

いくら加害者が謝罪したところで、亡くなった方はもう帰ってきません。生き残った方の心の傷や生活も元通りになるわけがありません。

ですが、加害者は「自分のこれからの生活のため」に被害者に赦しを求めます。

しかも、上の言葉にありますように、真に心から悔やんでいるとは到底思えない態度で「赦してくれ」と被害者に求めるのです。そして彼らはほとんど裁かれることなく釈放され、今まで通りに生活を始めるのです。

これは読んでいて精神的にかなり苦しかったです。

そして極めつけは続編の『隣人が殺人者に変わる時 和解への道―ルワンダ・ジェノサイドの証言』に出ていた加害者の次のような言葉でした。

「俺たち殺人者は、自分たちの破滅的な悪行をまったく忘れていない。俺たちが奪った命は、記憶の中にきちんと並べられている。これと反対のことを言っている者たちは、自分たちが嘘つきだと証明しているようなものだ。刑務所では、沼で死んだ人を思い出し、そして考えた。特にたくさん殺した者は、その報いで今度は自分が殺されるだろうとね。俺は沼の死体のことを考えるといつも恐怖に襲われ、マラリアの発作よりもひどいショックを受けた。でも、後になって赦免されたとき、その恐怖はどこかにいっていた。俺はなにもかも癒されたと思った」

かもがわ出版、ジャン・ハッツフェルド、服部欧右訳 『隣人が殺人者に変わる時 和解への道―ルワンダ・ジェノサイドの証言』 P 147

この証言を読んで私が思ったのは、「この人は殺人そのものに対する罪の意識はなく、自分が逮捕され、処刑される恐怖しか考えていなかったのではないか」ということでした。

その証拠に「法的に」釈放された途端、恐怖はどこかに行き「俺はなにもかも癒されたと思った」と彼は口にしています。

彼にとって人を殺したことに対する罪の意識はいかほどのものなのでしょうか。

他の加害者の多くも、残虐な方法で苦しめながらツチ族を殺したことに対してほとんど良心の呵責を感じていないかのような話しぶりです。ほとんどが「仕方がなかった」、「命令に背けば自分が殺されていたかもしれないから」と自分の行動の責任を考えようとはしません。

これはアーレントが主張した「悪の陳腐さ」の概念を連想させます。社会の歯車としての「仕事」をしていただけで自分が「望んでしたこと」ではない。しかもあまりに多くの人間がこの虐殺に関わってしまっている。その全員を有罪として裁くのか。どこまでを虐殺の実行者として処罰するのか。

この「虐殺に関わった大量の人間をどうするのか」という問題は非常に大きな問題です。

あまりに多くの人が「仕事」として殺戮に関わってしまった。誰もが権力の歯車として動いた。

そうなってしまったら誰がその責任を取るのでしょうか。トップや上層部だけでしょうか。実際に手を下した人はどうなるのでしょうか。それを後方支援していた人はどうなるのでしょうか。虐殺を知っていながら傍観していた人はどうなるのでしょうか。

しかもここルワンダではさらに恐ろしいことに、ツチ族男性の多くが実際にマチェーテ(なた)を握り殺害に関与し、女性も略奪に加わっています。こうなってしまえば、有罪ではない人間はほとんどいなくなってしまいます。

こうした法的な問題もこの本から考えさせられることになります。

ですがやはり一番強烈なのは、これほどの悪を犯した者自身が「自分たちには〈赦し〉が与えられなければならない」、「新しい生活をしたい」と無邪気に言えてしまうその恐ろしさでした。

しかもルワンダのジェノサイドで恐ろしいのは、加害者と犠牲者がまた同じ場所で生活しなければならないという事情があったのです。加害者がどこか遠い所で収監されていたり逃亡生活をしていたとしたらまだ自分の目につくことがありません。しかしルワンダはそうしたことも許されません。ルワンダには次のような事情があったのです。

RPF(ルワンダ愛国戦線:ツチ中心の反政府軍)の勝利により内戦が終結して九年が経過し、地方都市ニャマタにも、殺人を犯し投獄されていたフツたちが早々に釈放され戻ってきた。新政府は国の安定化と経済復興のため、抑留中の殺人者(及び殺人加担者)十数万人をできるだけ早く釈放しなければならなかったのだ。その結果ツチの生存者たちは思ったよりも早く、家族や知人をマチェーテで惨殺した殺人者たちと再会することになる。殺人者は罪を悔い、より早い和解と社会復帰を望むが、生存者側には納得できないものが残る……。

かもがわ出版、ジャン・ハッツフェルド、服部欧右訳 『隣人が殺人者に変わる時 和解への道―ルワンダ・ジェノサイドの証言』 P309

残忍な殺人者に変貌したいわゆる普通の人たちは、ジェノサイド後生存者と和解し、また元の普通の人間に戻ろうとする。もちろん、これは生存者にとって受けいれられるものではなかった。惨殺された家族や仲間の記憶、そして何十日間も毎日恐怖と共に逃げ続けた自らの記憶がそれを許さなかった。しかし、生存者と加害者は否応なく同じ土地で人生を再開し、共同生活を送らねばならなかった。国の復興と安定のため、新政府主導で半ば強引に和解政策が進められていったのである。ジェノサイド後は、「ルワンダはひとつ」を合言葉に、やがてツチ、フツという言葉は禁句となっていった。国民は四月の追悼週間以外は、自身のジェノサイド体験をほとんど誰にも語ることなく、新政権の強い指導に従っていった。その結果ルワンダは一五年あまりで「アフリカの奇跡」とも呼ばれる見事な経済成長を成し遂げたのである。しかし、彼らは納得し満足しているのだろうか。数年前にこのように語ったルワンダ人がいる。

「ルワンダでは政府に逆らうことはできないんだ。旧政権はジェノサイドを命じ、市民はそれに従った。新政府は赦せというから、今度はそれに従っている。ルワンダは否応なしに政府に従わなければならない国なんだ」

現在のルワンダの危うさはここにもある。政府の圧力と権威に従順な国民性。ジェノサイドの根本原因の一つが、まだ未解決のまま残されているような気がする。それは現在の日本にとっても他人事とはいえないような問題であるが……。

かもがわ出版、ジャン・ハッツフェルド、服部欧右訳 『隣人が殺人者に変わる時 和解への道―ルワンダ・ジェノサイドの証言』 P310

彼らが行った虐殺の罪は政府によって「赦された」。

犠牲者はそれに従って「彼らを赦し」、共に生活しなければならない。

私はこうしたルワンダの状況を知り、どうしても考えざるをえませんでした。

「悪の陳腐さ」は免罪符なのだろうかと・・・

あまりに多くの人間が権力の歯車として関わってしまったら、それを裁くことはできない。

そしてそれをいいことに、「仕方なかった」と自分の罪の意識も捨て去ってしまう。

ですがどうでしょうか。正直、私は納得できません。加害者は本当に歯車のように動いていたのでしょうか。虐殺を楽しんでいなかったか。なぜ命令されてもいないのにわざわざ苦しみを増すような殺し方をしたのか。殺した後に飲めや歌えやの宴会を繰り返していたではないか。それも「仕方なかった」のでしょうか・・・?

たしかに、「仕方なかった」面もあったかもしれません。

ですがどうしても私は引っかかってしまいます。彼らは「悪の陳腐さ」を隠れ蓑にして自分の罪をなかったことにしていないだろうか。加害者の言葉の軽さはこうしたことの証明ではないだろうか。

そんなことを思ってしまったのでありました。

となればここでもう一度改めて「悪の陳腐さ」というものそのものについて考えてみるのも大切なのではないかと私は感じました。

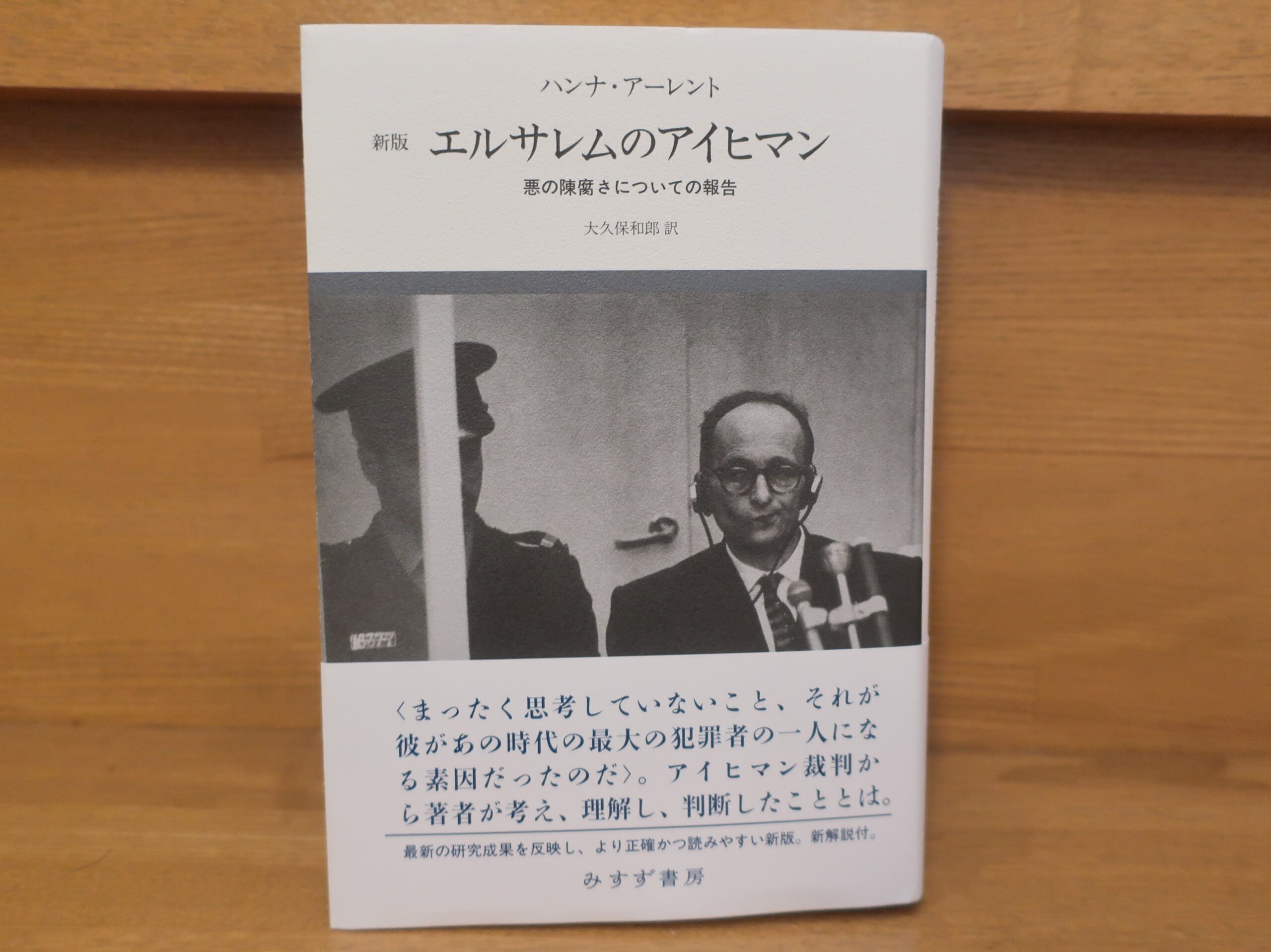

というわけで私はハンナ・アーレントの『エルサレムのアイヒマン――悪の陳腐さについての報告』を読んでみることにしました。

アーレントの「悪の陳腐さ」という言葉は有名ですが、これまで私はアーレントの著作を読んだことがありませんでした。なぜか彼女の作品から距離を置いていた自分がいたのです。

ですがこれはいい機会なのかもしれません。

次の記事ではアーレントの『エルサレムのアイヒマン――悪の陳腐さについての報告』をご紹介します。そしてその後、さらに驚きの作品、ベッティーナ・シュタングネト著『エルサレム〈以前〉のアイヒマン』もご紹介します。

「悪の陳腐さ」という概念を考えていく上でこの2冊は非常に重要な作品です。じっくりと読んでいきたいと思います。

以上、「アーレントの「悪の陳腐さ」は免罪符になりうるのか~権力の歯車ならば罪は許される?ジェノサイドを考える」でした。

※ルワンダのジェノサイドと「赦し」の問題についてはこの記事で紹介した『隣人が殺人者に変わる時』三部作とレヴェリアン・ルラングァの『ルワンダ大虐殺 世界で一番悲しい光景を見た青年の手記』が非常に参考になります。ぜひ手に取って頂きたい作品です。

Amazon商品ページはこちら↓

次の記事はこちら

前の記事はこちら

関連記事

コメント