ゴーゴリ『鼻』『狂人日記』あらすじと感想~ドストエフスキー『二重人格』に強い影響を与えた「ペテルブルクもの」の代表

『狂人日記』と『鼻』の概要とあらすじ

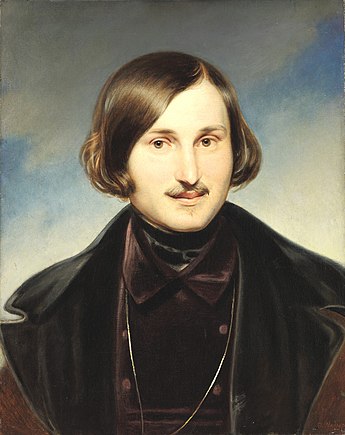

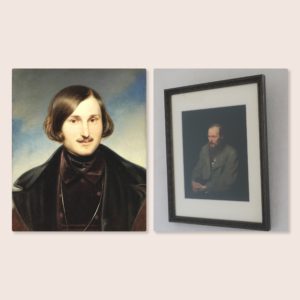

ゴーゴリは『ネフスキイ大通り』に引き続き1835年に『狂人日記』を、1836年に『鼻』を発表しました。これら2作品も「ペテルブルクもの」の代表として知られています。

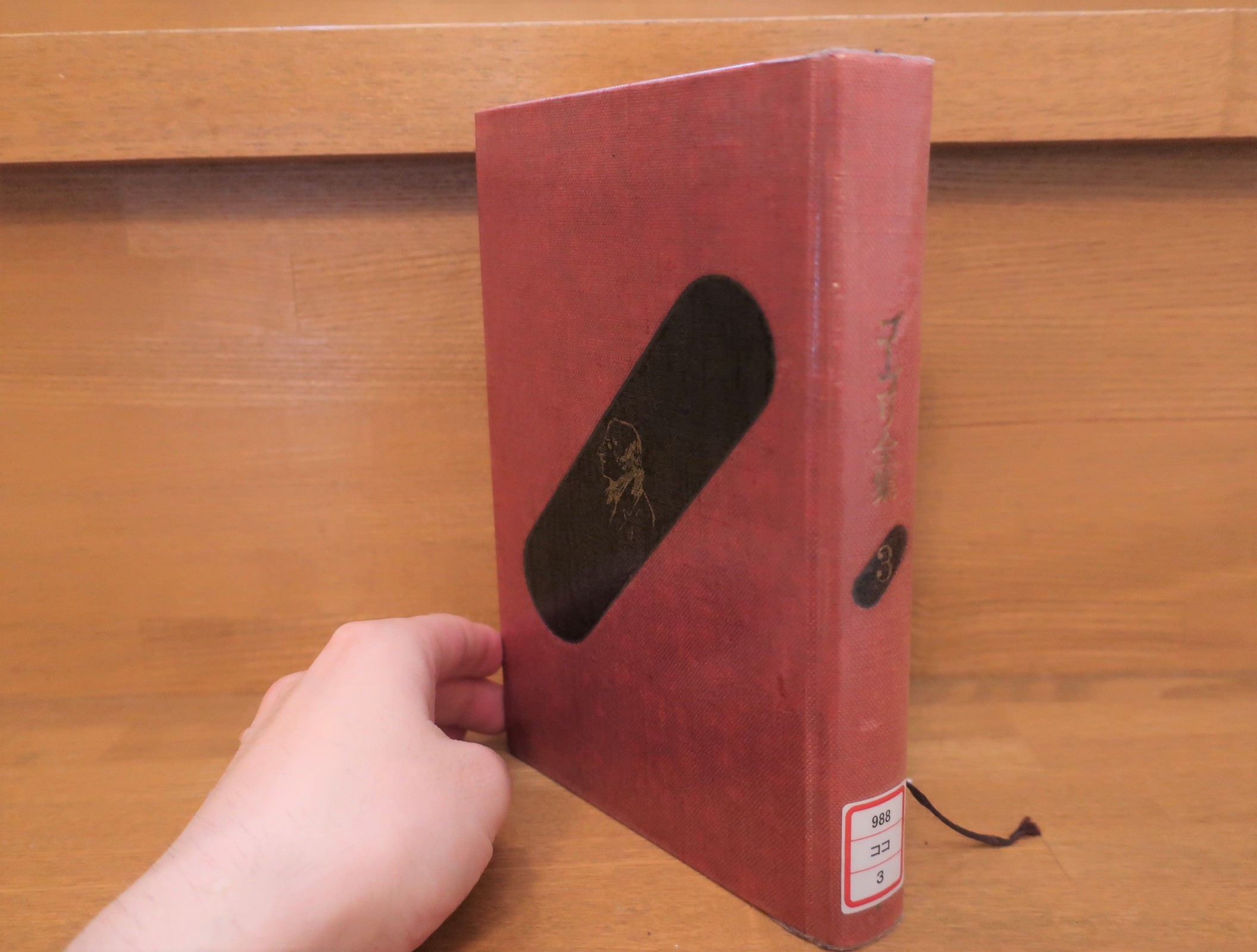

私が読んだのは河出書房新社、横田端穂訳の『ゴーゴリ全集3 中編小説』所収の『狂人日記』と『鼻』です。

早速それぞれのあらすじを紹介したいところなのですが、これがまた難しい・・・

『狂人日記』はまだなんとかなるのですが『鼻』となると内容があまりに突飛でシュールすぎるので説明に困ってしまうのです。残念ながら巻末の解説にもあらすじは載っていません。

書くのも苦労したのですが、まずは『狂人日記』のあらすじを見ていきましょう。

主人公ポプリーシキンはうだつの上がらない下級官吏で、長官の娘に好意を持っています。しかし身分があまりにも違いますし、そもそも男としての魅力もないのですからうまくいきようもありません。それでも彼なりに長官に尽くし、寵愛を受けようとするのですがあいかわらずのうだつの上がらなさっぷりです。これではうまくいかなさそうです。

この作品はそんなポプリーシキンが精神に異常をきたし狂っていく様を彼の日記を通して見ていくという物語です。

彼はある日突然犬の会話が聞こえるようになり、長官の家の犬が出した手紙を読もうとします。(すでに意味不明ですね)

そしてしばらくすると自分がスペインの王位継承者であると思い込み、最後は精神病院に連行されていくことになります。

この作品のすごいところは狂っていく人間を他者が外側から描写したのではなくて、今まさに自覚なしに狂っていく人間の思考や言動を一人称で描いているところにあります。

犬の声が聞こえてくるところまではまだいいのですが、自分がスペイン王位継承者だと言い出すあたりからかなり不気味さが出てきます。ゴーゴリ流のユーモアが全開なのでくすっと笑ってしまうのですがちょっと考えてみると背筋がぞっとするような不気味さがやってくるのです。

その箇所を少しだけ紹介します。

二〇〇〇年。四月四十三日。

河出書房新社、横田端穂訳『ゴーゴリ全集3 中編小説』P296

今日はたいへんめでたい日だ!スぺインに王さまがいたのだ。見つかったんだ。その王さまというのは―このおれだ。今日はじめて、それがわかった。うちあけていえば、まるで稲妻が照らすように、ぱっとそれがわかった。いったい、どうしてこれまで自分が九等官だなんて思っていられたのか、わけがわからぬ。あんなとほうもない狂気じみた空想が、まったくどうしておれの頭へ浮かびえたのか?まだだれ一人おれを精神病院へ入れようと思いつかないうちで、まあまあ仕合わせだった。いまや、おれにはなにもかもがはっきりした。いまのおれには、いっさいが手に取るようにはっきり見える。ところが、いままでは、いっさいがまるで霧にでもつつまれたようで、おれにはなにもわからなかった。どうしてそうだったかというと、人々が、人間の脳髄は頭のなかにあると思いこんでいるせいだと、おれは思う、そんなわけのものじゃけっしてないのだ、人間の脳髄はカスピ海のほうから風に送られてやってくるのさ。

日付に注目してください。もはやかなり狂っているのがすでにわかります。

最後の「人間の脳髄はカスピ海のほうから風に送られてやってくるのさ。」という言葉はもう常軌を逸しています。この作品は日記調で書かれていて割と淡々と進んで行きます。前半はまだ理解できるのですが終盤はずっとこの調子です。

あまりに突飛で、しかもそれをポプリーシキンは大まじめに書くものですからとてつもなくシュールなものになっています。そのシュールさに思わず笑ってしまうのですがなかなかにこの作品は不気味です。

さて、まだまだ『狂人日記』のことを紹介したいのはやまやまなのですが次の『鼻』にも進んで行きましょう。

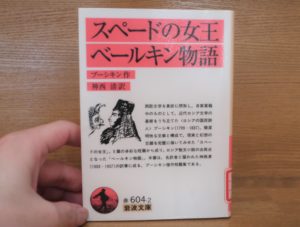

こちらの主人公も下級官吏のコワリョーフという男で、ある日目が覚めると鼻が無くなっていることに気付きます。

彼は警視総監のところへ行こうと外に出ますがそこで出会ったのはなんと、辻馬車から降りてくる「自分の鼻」だったのです。

彼は意を決して鼻に声を掛けるも軽くあしらわれ逃げられてしまいます。

さてコワリョーフの運命やいかに!?

というのがあらすじなのですが、いかがでしょうか。さっぱりわけがわからないですよね。私もどう言っていいのかわかりません。

まず鼻が朝起きたら消えているのも謎。さらにあろうことか馬車から自分の鼻が降りてきて歩き出し、会話までするとは意味不明の極みです。

イメージすることすら困難ですよね。鼻が馬車から降りてくるってどういう情景でしょうか。身体はどうなってるんでしょうか。足はあるんでしょうか。胴体は?手は?

ですが不思議なことになんとなくこの後もスラスラ読めてしまい、さも鼻が私達と同じように生きて動いているかのように感じてしまうのです。ここがゴーゴリのすごいところです。

幻想的な街サンクトペテルブルクでは何が起こっても不思議はないというのがペテルブルクものの主題です。

まさしくこの作品は幻想的な都市ペテルブルクの不思議を最高度に表現した作品と言えそうです。

ドストエフスキー『二重人格』とのつながり

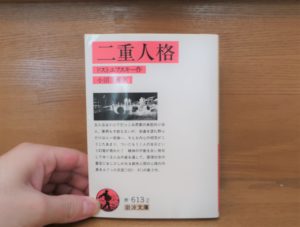

ドストエフスキーの『二重人格』は1846年に発表された作品で、デビュー作『貧しき人びと』の華々しい成功で一躍文壇の寵児になった彼の第二作目にあたる作品です。

他の版では『分身』というタイトルで翻訳されているように、この作品では下級官吏ゴリャートキンが精神に異常をきたし、目の前に自分の分身が現れるという筋書きとなっています。

これは明らかにゴーゴリの影響が見て取れます。精神異常をきたしていく下級官吏ポプリーシキンの『狂人日記』、自らの鼻が目の前に自分の分身のごとく現れたコワリョーフの『鼻』がこの作品のベースになっています。

モチューリスキーの『評伝ドストエフスキー』ではこのことについて次のように述べられています。

ドストエフスキーはゴーゴリの人物像と言葉との魔法の埒外には出ていない。青年作家の『狂人日記』の作者とのたたかいはつづいている。ふたたびゴーゴリを模倣しながら、彼はこの幻影を乗りこえようとしている。同時代人たちはこの模倣は見てとったが、「反逆」には気づかなかった。(中略)

ドストエフスキーは狂気を基本のテーマとして、第一章から発狂のきざしの見える主人公を描いている。ゴーゴリの場合は、狂気のモチーフは単に凝った文体上のゲーム(日記や犬の往復書簡)だった。

ドストエフスキーは、狂人の心理、発病とその進行の過程を深く掘りさげている。師ゴーゴリの幻想的グロテスクふうから、彼は心理小説を作りあげている。

精神分裂症のモチーフは、ゴーゴリのもうひとつの小説『鼻』から暗示されている。六等官コワリョフもやはり「二つに分裂している」。彼の体の一部は独立した存在となって、制服を着て馬車を乗りまわす。自分の持ち主から離れた鼻は、彼の分身のごときものになる。

コワリョフは新聞社の広告係にいろいろ説明する。「わたしが広告しようとしているのはプードル犬のことではありません。わたし自身の鼻のことなんです。ですから、それはほとんどわたし自身のことじゃありませんか」(中略)

ドストエフスキーは、ポプリシチンの発狂とコワリョフの分裂というゴーゴリの二つのテーマを結合させながら自身の「分身」を創りあげた。たぶん、『死せる魂』の作者の幻想的な中篇小説を熟読しながら、そのイデーを彼なりに把握しようとしたのである。

ポプリシチンはどうして発狂したのか。コワリョフはどうして分裂症になったのか。どうしてこんなことが起こりえたのか。ドストエフスキーは、ゴーゴリを「もう一度とらえなおす」課題をみずからに課したのである。

モチューリスキー『評伝ドストエフスキー』松下裕・松下恭子訳P51-52

※一部改行しました

ドストエフスキーの同時代人たちはこうしたドストエフスキーの意図を理解することができず、この作品を単なるゴーゴリの模倣だと非難しました。

しかしドストエフスキーの中ではまったく違うことを意図してこの作品を書いていたのです。

もうひとつ解説を見てみましょう。

九等官ヤーコフ・ペトローヴィチ・ゴリャートキンは、ぺテルブルグのじめじめした霧の産物であり、幻想的な都市に住んでいる幻影である。

彼は役所、官房、往復文書、発信書類、行政上の「譴責」、権謀術数、官等、上申書といった奇怪な世界に出没する。国家という機械の小さな「歯車」であり、役人の大群のなかに埋もれてしまう砂つぶのような存在である。

ニコライ一世の官僚体制は、その巌のような重量で人間の個性を押しつぶしている。国家はその人間の番号と官等は知っているが、人物そのものは知らない。

おしなべて人間の価値は等級表に取ってかわられている。どの役人も互いに見わけがつかず、彼らの重要度は、内的なもの、徳性によってではなく、外的なもの、地位とか役職によって決まってくる。

人びとの関係は機械化され、人そのものは物と化している。役所にゴリャートキンの分身が現われても、役人のうち誰ひとりとしてこの「自然の奇蹟」に気づく者はいない。誰ひとりとしてその人間の顔を見ないが、物に顔などあるものか、というわけだ。物は互いに置きかえられるから、ゴリャートキンが分身に取ってかわられようと驚く者などいないのだ。

モチューリスキー『評伝ドストエフスキー』松下裕・松下恭子訳P52-53

※一部改行しました

まさしくドストエフスキーはゴーゴリの「ペテルブルクもの」で描かれた問題を先に進めました。ドストエフスキーもゴーゴリと同じように華の首都ペテルブルクの現実を見、幻滅を味わったのです。

ゴーゴリはそれをユーモアあふれる風刺作品としてこの世に送り出しましたがドストエフスキーはそれを深刻なほど掘り下げて自らの作品を作り上げたのです。

この作品は単なるゴーゴリの模倣とは到底言えないほどの深みを持った作品として私たちの前に現れます。

『評伝ドストエフスキー』では『二重人格』という作品がもつ意味を次のように述べています。これは現代を生きる私たちにも非常に重要な指摘ですので少し長くなりますが引用します。

官僚機構に押しつぶされ荒廃させられた人間は、いったいどんな人間でありえるか。自分の人格が次第に失われて行くのを感じている人間はどんな目にあわねばならないか。

彼は、この「書類」の王国の外では自分には人びととの真の結びつきがない、自分は空虚と無限の孤独とのなかに置かれていると自覚しないわけにはいかない。

こういう人間は恐怖と全面的な脅威とにさらされて生きて行かなければならない。

どういうふうにして彼は自分を守り、自分は自分なのだ、自分は唯一のもの、二人といない自分なのだ、自分を取りかえることもすりかえることもできないのだと証明できるだろうか。

どういうふうにして彼は自分が本人であると証拠だてることができるのか。

ゴリャートキンは、自分のまわりに柵をめぐらし、没個性的な集団から離れ、孤独にすごすことによって自分の人格を救おうとしている。追いつめられた鼠のように、自分の穴に身をひそめている。彼はドストエフスキーの最初の「地下生活者」である。

彼は、だれからも手を触れられないように「離れて」立っていることを望み、だれの注意もひかないように「みんなと同じであること」な願っている。

「おれはこう言いたいんだ」と彼は途方にくれてつぶやく。「おれは自分の道を、人とは別の道を歩いている。おれは別だ。自分の知っているかぎり、おれは誰の世話にもなっていない……。おれはおとなしい人間だが、おれの道はほかのやつらとは別なのだ」(第二章)。

個性を奪われた人間の卑屈さ、臆病さは、躁鬱病的な語調で描写されている。「おれは平気の平左だ。おれはみんなと同じように独立した人間なんだ。いずれにしても、おれの小屋は離れて立ってるんだ……。おれは誰とも知りあいたくはない。誰もおれにさわってくれるな。おれのほうもさわらないから。おれは『離れて立ってる』んだ……」

この「離れて立っている」には、臆病な無力さがひびいている。ゴリャートキンは知っている―自分にはわが身を守る力がない、自分の穴にすばやくかくれることもままならない、自分には「確固たる性格」がない、自分の人格はとうに木端微塵になっている、と。生きることと生きることの責任とにたいする怖れが「そっと立ち去りたい」、「消えてしまいたい」という弱気な願望を生んでいる。

モチューリスキー『評伝ドストエフスキー』松下裕・松下恭子訳P53-54

※一部改行しました

この作品は19世紀ロシアで書かれた作品です。しかしここで述べられていることは現代日本を生きる私たちと何ら変わらないことです。私達とドストエフスキーは同じことに苦しみ、生きづらさを感じていたのです。

ドストエフスキーはそれをゴリャートキンを通して私たちに投げかけてくるのです。

私自身この作品を読んでとても心打たれるものがありました。個人的にも『二重人格』はドストエフスキー作品の中でも上位にくるくらい大好きな作品です。

周りとうまくなじめない。なじみたいとは思うのだけれどもやはりなじみたくもない。自分って何なんだ。何でこんな自分になってしまったんだ。どうしたらいい。なんで自分はこんな卑屈なんだ。自分がおかしいのか?どうしたら私は生きていけるのか。なんでこんなに苦しまなければならないのだろう。

そんな悩みを抱えている人にはぜひ読んでほしい作品です。ここに同じ悩みを抱えた人間のドラマがあるのです。ドストエフスキーはそうした人間の味方です。

私はこの作品を読んで、そうした人間の苦しむ姿に共感し共に苦しみながらも、同じ苦しみを耐えている人が他にもいるのだという不思議な安心感を感じたのを覚えています。

もちろん、この作品はハッピーエンドではありません。

ですが何か心にずっしり来るものを私達に残してくれる作品です。

ドストエフスキーはゴーゴリの『狂人日記』、『鼻』の影響を強く受けて『二重人格』を作り上げました。

ゴーゴリの作品を読むことでドストエフスキーが何を言いたかったのかがより明らかになってくるように思えます。

作品としても『狂人日記』、『鼻』は非常に面白いです。シュールな笑いの極みと言ってもいいかもしれません。

シュールな笑いの好きな方はまずはまると思います。

ゴーゴリ作品の中でもずば抜けて読みやすい作品となっていますのでとてもおすすめです。

以上、「ゴーゴリ『鼻』『狂人日記』ドストエフスキー『二重人格』に強い影響を与えた「ペテルブルクもの」の代表」でした。

Amazon商品ページはこちら↓

次の記事はこちら

前の記事はこちら

関連記事

コメント