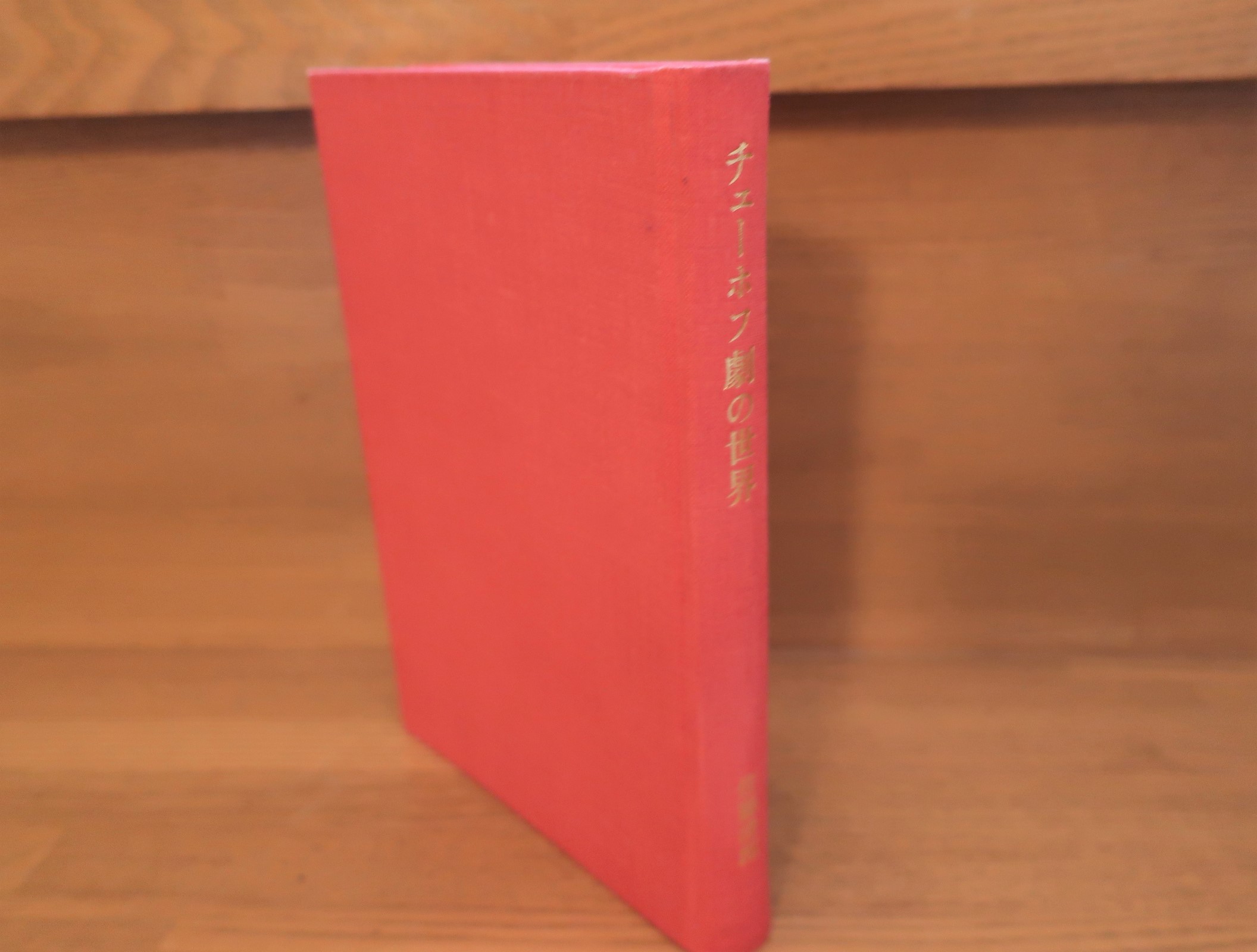

佐藤清郎『チェーホフ劇の世界』あらすじと感想~チェーホフの劇作品に特化したおすすめ参考書!

チェーホフ劇のおすすめ参考書!佐藤清郎『チェーホフ劇の世界』概要と感想

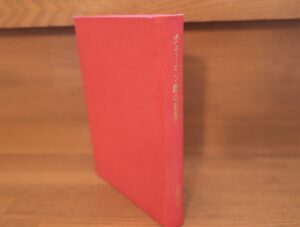

佐藤清郎著『チェーホフ劇の世界』は1980年に筑摩書房より出版されました。

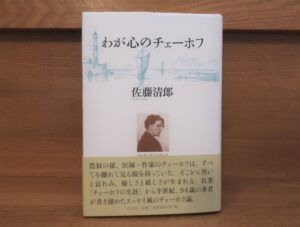

佐藤清郎氏に関しては何度もこのブログでご紹介していますが、改めてプロフィールをご紹介します。

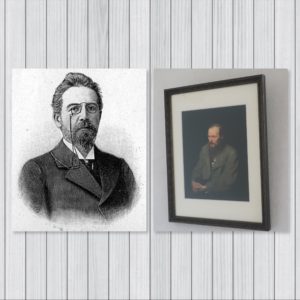

佐藤 清郎(さとう せいろう、1920年(大正9年)11月26日)は、日本のロシア文学者。

東京生まれ。1942年満洲国立大学哈爾浜(ハルピン)学院卒、大同学院卒。大阪大学教養部助教授、教授、1975年言語文化部教授、1980年早稲田大学客員教授、1991年退任。チェーホフを中心に帝政ロシアの文学者について伝記的著作を多く行った。

Wikipediaより

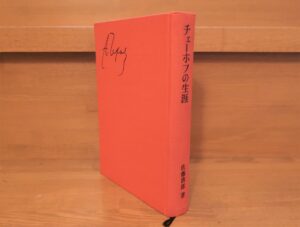

以前このブログでもご紹介しましたように佐藤氏はチェーホフを中心にロシア文学を研究された学者さんで、この本の他にも『チェーホフの生涯』や『チェーホフ芸術の世界』、『観る者と求める者 ツルゲーネフとドストエフスキー』など多数の著作を残しています。

さて、この本の特徴ですが、タイトルにありますようにチェーホフの劇に特化して解説された参考書です。同氏の『チェーホフ芸術の世界』では小説作品のみを取り上げていたのに対し、こちらの本では小説作品は取り上げません。

チェーホフ四大劇の『かもめ』、『ワーニャ伯父さん』、『三人姉妹』、『桜の園』だけでなく、『イヴァーノフ』という作品についてもかなり詳しく解説されています。

演劇とは何か、小説とは何が違うのかということまでじっくり考察された盛りだくさんな本です。四大劇だけでなく、舞台演劇に興味のある方にもおすすめしたい内容となっています。

巻末のあとがきに佐藤氏のチェーホフ劇に対する言葉が述べられており、それがとても心に刺さる文章でしたので少し長くなりますがここに紹介します。

最近、特に私の眼を惹いた二つの発言がある。いずれも「朝日新聞」に載ったもので、寺山修司と小田島雄志の言葉だ。

寺山は「ニューヨーク演劇通信」という文章の中で、「ニューヨークでは、ひとりごとを言いながら歩いている人間がひどく目についた」「人々は灼けるように孤独である」と言っている。

寺山が問いかけたかったのは、「演劇性の感化力とは何か」ということであるが、「孤独」という点を取り上げるなら、八十年前に書かれたチェーホフの人物たちこそ、すでに「灼けるように孤独」ではなかったか。

てんでんばらばらな孤独な人たち、彼らはどう生きたらいいのか、それを問いかけたのがチェーホフ劇ではないのか。

彼の問いかけは確かに革命前のロシヤの現実を踏まえてのものだが、優れた芸術がすべてそうであるように、それはまた永遠の問いかけでもある。いくつもの主義の興亡、戦争や公害等を経てきた今日でも、更めて問い直すべき問いかけである。チェーホフは答えを出していない。答えはそのときどきの観客が出さねばならないのである。

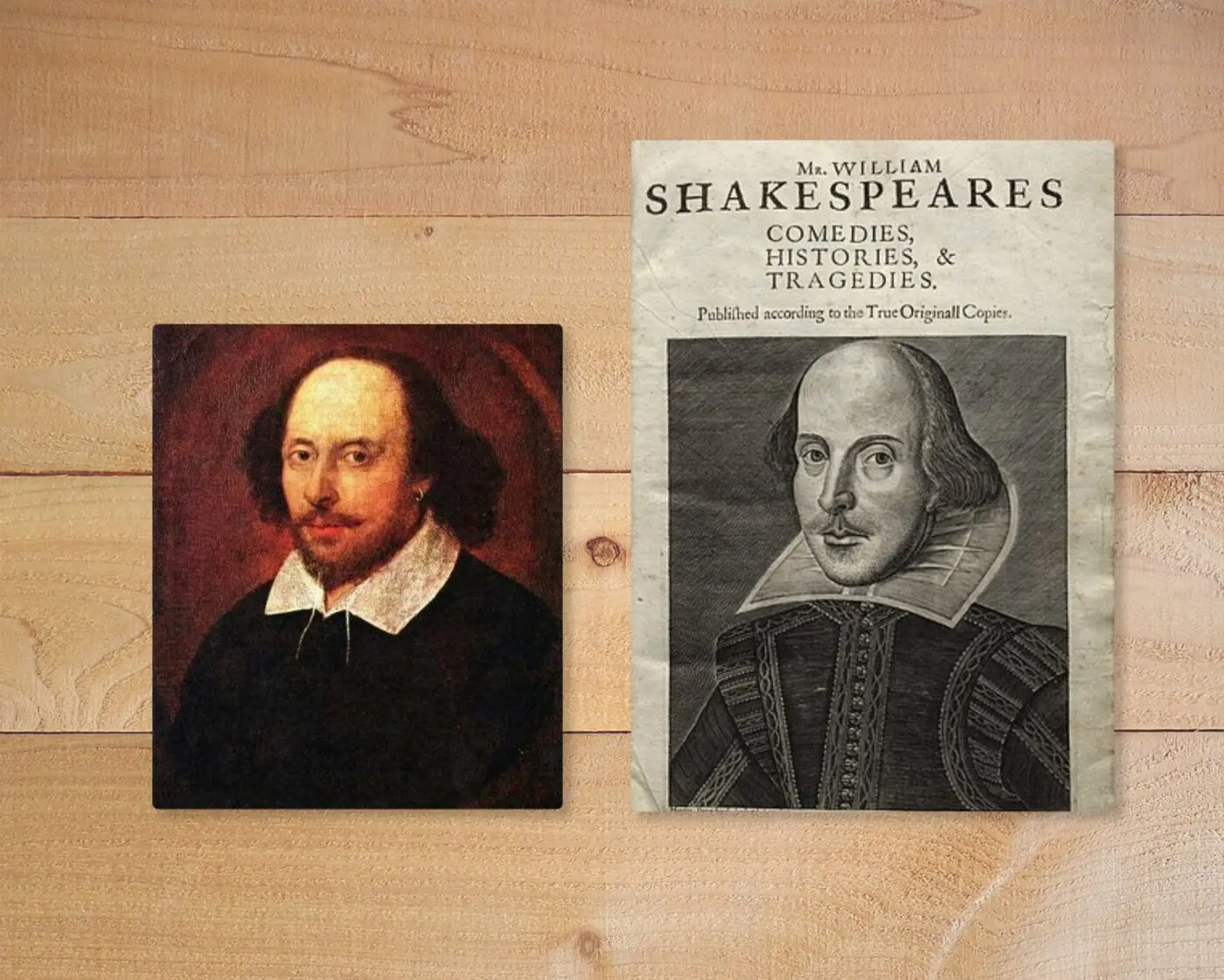

その底から聞えてくる熱い問いかけの声を聞き取らねば、チェーホフ劇の理解から遠のく。状況の「提示」にのみ坐りこんで、「問いかけ」を忘れた演出が多すぎはしないか。寺山は「シェイクスピアやチェーホフの幸福な再生」を批判しているが、「幸福な再生」よりも「不幸な再生」のほうがはるかに多い。

小田島の文章はシェイクスピアの翻訳が一段落ついての感想であるが、その中でこう言っている。「ハムレットもオセロも、リアも、マクべスも、もともと確固とした価値基準をもっていた」のに、結局、終幕でその基準が破れ、混沌に陥っている、と。

ここまでは肯定できるが、その先に、読み方によっては混沌礼讃とも取りかねぬ言葉がつづくのだ。なるほど、混沌のない社会はむしろ不健康であろう。だが、混沌から這い出す努力のない社会も病的ではないか。

「混沌の提示」は、讃美ではなくして問いかけではないのか。提示のみでなく、問いかけがあるからこそ、シェイクスピアもチェーホフも生きのびたのではないか。

気になるのは、混沌に安居し、足踏みして満足している人たちのあまりにも多いことだ。現実からも、舞台の上からも、「どうにかなるさ」「どうなったってかまうものか」といううそぶきが聞えてくるようだ。

寺山が見たニューヨークの「灼けるような孤独」など、残念ながらこの国にはない。この国には幸か不幸か徹底がない。甘えが邪魔するのだ。二葉亭愛用の言葉を借りれば、何事にも「程々主義」なのである。

もっと「孤独」や「個」に徹したほうがいい。本当の芸術創造は、そういう「底」から生れてくるものである。感覚や情念の手放しの讃美こそ「程々」にしたほうがいい。

「芸術家は一過的、一時的なもののそばを通りすぎる」とチェーホフは言った。時流を無視せず、時流にとらわれず、彼は生きたのである。その眼を「高い所」において、人間世界を見ていたのだ。厳しさと優しさのこもった眼で。

かつて久米正雄はチェーホフを目して、「永遠に『昨日』の作家」だと言った。私は言いたい。「チェーホフは、永遠に『今日』と『明日』の作家だ」と。彼には感傷も昨日への執着もない。彼にとって大事なのは「今日」と、明日」であった。彼は「現在」と「永遠」を同時に見ていたのである。

筑摩書房、佐藤清郎『チェーホフ劇の世界』P262-263

※一部改行しました

この文章は1980年のものですが、これは今の私たちにとっても大きな意味がある言葉なのではないでしょうか。

佐藤氏は「この国には幸か不幸か徹底がない。甘えが邪魔するのだ。二葉亭愛用の言葉を借りれば、何事にも「程々主義」なのである。」と言いました。

そして「気になるのは、混沌に安居し、足踏みして満足している人たちのあまりにも多いことだ。」「混沌から這い出す努力のない社会も病的ではないか」と述べます。

大変な世の中だと言うのは簡単ですが、ではそこからどうするのかということに本当につながっているのか。何もせずに困った困ったと言いつつそれに安住していないか。チェーホフの演劇はまさにそれを問うてくると佐藤氏は述べるのです。

この本が出た1980年からすでに40年以上も経ちましたが私たちはこの問いかけにどう答えるでしょうか。

これはもしかしたら40年前よりもさらに難しい問いになっているかもしれません。私たちは40年前から進歩したのでしょうか、それとも退化しているのでしょうか。

チェーホフを読んでいると個人の心の問題だけでなく時代と社会にも目を向けることになります。

こうしたところもチェーホフの素晴らしい点であると私は思います。

入門書としては少し難しいですがチェーホフ劇をもっと知りたい人には非常におすすめな1冊です。

以上、「佐藤清郎『チェーホフ劇の世界』チェーホフ劇のおすすめ参考書!」でした。

Amazon商品ページはこちら↓

次の記事はこちら

チェーホフおすすめ作品一覧はこちら

関連記事

コメント