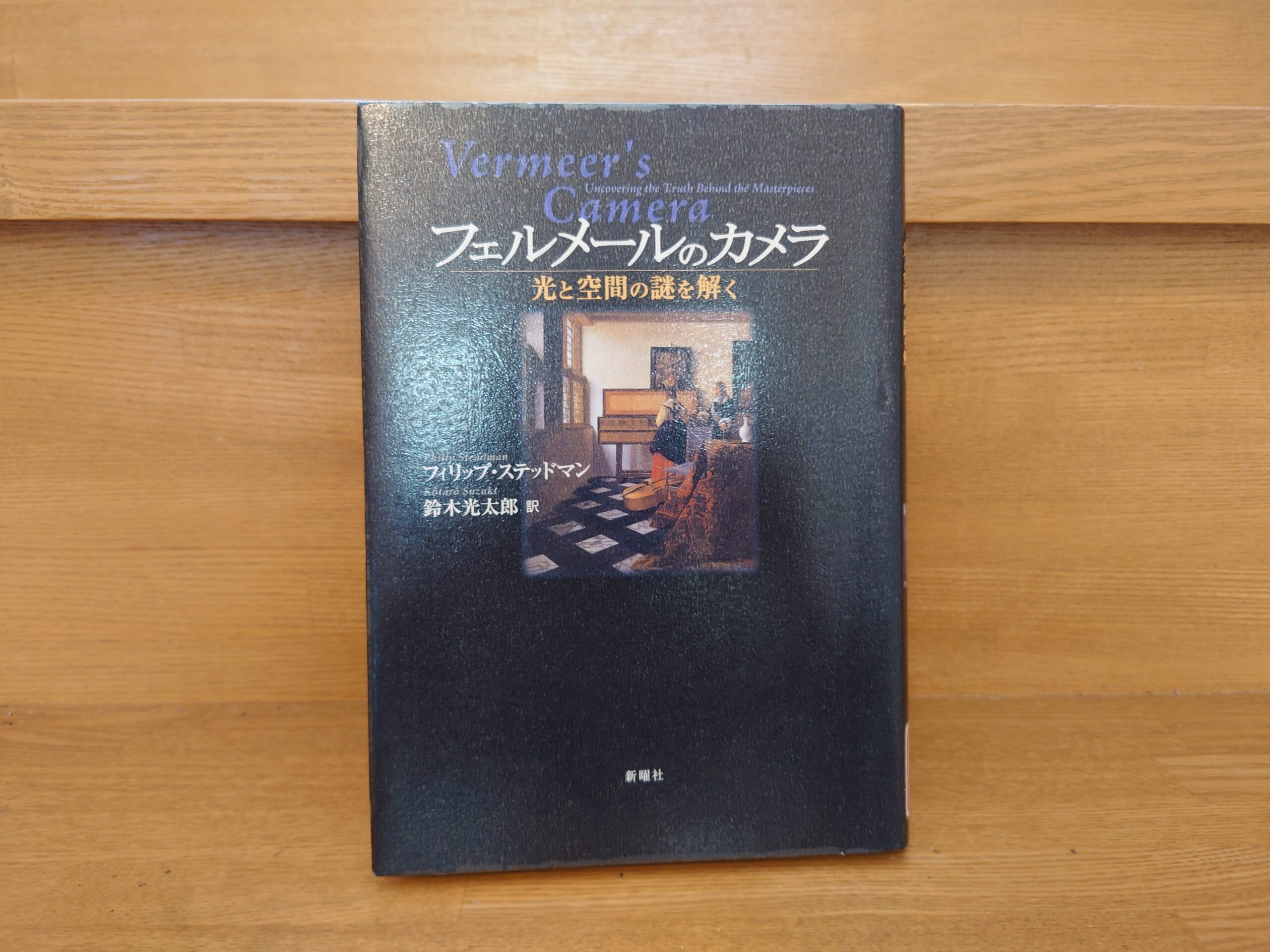

F・ステッドマン『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』あらすじと感想~写真機の先祖カメラ・オブスクラとは何かを知るのにおすすめ!

F・ステッドマン『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』概要と感想~写真機の先祖カメラ・オブスクラとは何かを知るのにおすすめ!

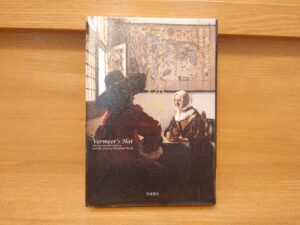

今回ご紹介するのは2010年に新曜社より発行されたフィリップ・ステッドマン著、鈴木光太郎訳の『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』です。

早速この本について見ていきましょう。今回はこの本の「はじめに」で書かれている箇所をご紹介します。

オランダの画家、ヨハネス・フェルメール(1632-75年)は、カメラ・オブスクラを用いて絵を描いた。本書では、彼がどのようにそれを用いたのかを正確に示そうと思う。カメラ・オブスクラと、写真用のカメラの前身で、ピンホール(針穴)の開いた、あるいはレンズのついた簡単な装置である。光景の像がスクリーン上に投影されるので、その像をなぞることができる。

フェルメールが絵の構図や描画技法を助けるものとして、もしくはそのヒントとして、ある種の光学装置を用いていたようだということは、あとで見るように、美術史家の間で広く共有される見解になっている。

これまで研究者は、フェルメールのような傑出した技量をもった芸術家が、絵を制作する際に、カメラ・オブスクラを多用して輪郭のほとんどをトレースしたという考えをなかなか受け入れることができなかった。

この躊躇は、写真が芸術たりうるかどうかという古くからの議論ーもうとっくに決着がついた問題だと思っている人もいるかもしれないがーとも関係している。装置を用いて生み出される像を写しとることは、近代以前の芸術的技巧の基準からすると、能力のない者だけが頼る怪しげで不正な方法であるように見える。17世紀のオランダ美術における絵画の補助手段について概括するなかで、マーティン・ケンプは次のように述べている。

美術史家は全般的に、この証拠の意味を吟味したがらなかった。おそらくそれは、自分の好きな芸術家が一種のずるとみなされるものに頼っていたということが、あまりよいことではないように感じられたからだろう。

私は、フェルメールの場合にはこういった見方が的外れであり、歴史的にも適切でないと思う。

カメラ・オブスクラは、新たに明らかになった光学現象の世界に芸術家が分け入ることを可能にし、どのようにしてそれらを絵として記録すればよいかを探究させた。ここで心に留めておかねばならないのは、17世紀の半ばに、レンズの助けを借りて絵を生み出すということそれ自体が、斬新かつ特権的なものであったということである。瞬間を写しとる現代の写真にそれをたとえることは、いずれにしても誤りである。

絵を描くためにカメラ・オブスクラを使っても、それで制作の時間が短縮できたり、技術的に容易になったりするわけではない。むしろ、時間をかけた注意深い観察と分析が必要になる。さらに、室内にある対象をとらえる場合、カメラ・オブスクラは、芸術家に構図の制約を課さない。逆にそれは、構図を構成するプロセスそのものを助ける装置として使うことができる。モデルや家具をおいて、その位置を調整し、その結果生じる2次元の像への効果を判断できるのだ。

ケンプは次のように述べている。「カメラ・オブスクラの使用は、絵の構想と制作の各段階における芸術的選択をまったく規定しない」。

私が本書に示すのは、フェルメールの作品を驚くべきものにしている光、色調、陰影、色彩に対する執着が、光学像のもつ特質の観察と分かちがたく結びついている、ということである。

新曜社、フィリップ・ステッドマン著、鈴木光太郎訳『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』P1-2

※一部改行しました

この作品はタイトルにもありますように、フェルメールとカメラ・オブスクラという光学機械について書かれた作品です。

フェルメールとカメラ・オブスクラの関係についてはどの本でも書かれてはいたのですが、実際にそのカメラ・オブスクラがどういうものなのか、どのように使われていたのかというのはイマイチわかりにくいというのが正直なところでした。

そんな中この『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』はかなり詳しくカメラ・オブスクラについて知ることができます。図や写真も多数掲載されていますし、画家がこの機械をどのように使っていたかというのもわかりやすく説かれます。これはありがたいことでした。

そして著者は上の本紹介でも述べていましたように、フェルメールがカメラ・オブスクラによって映し出された映像をトレースして絵を描いていたという論を展開していきます。

ですがこの論は上にもありましたように、従来から多くの反論がなされてきました。

著者のステッドマンはそうした流れに対し、「反論への反論」と題して理論的に「カメラ・オブスクラトレース説」を展開していきます。

専門家ではない私にとってはなかなか理解するのに厳しいものがありましたが、ステッドマンはかなり詳しく解説を加えていきます。「ほぉ・・・そうなんだ」と思わず納得してしまうような説得力がこの本にはあります。

ただ、問題はそう単純ではなく、この「反論への反論」に対するさらなる反論もあるのです。

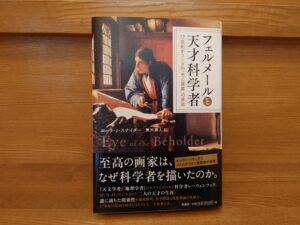

というのも以前当ブログで紹介したローラ・J・スナイダー著『フェルメールと天才科学者 17世紀オランダの「光と視覚」の革命』では次のように書かれていたのでありました。少し長くなりますが重要な指摘であるように思えますのでじっくりと読んでいきます。

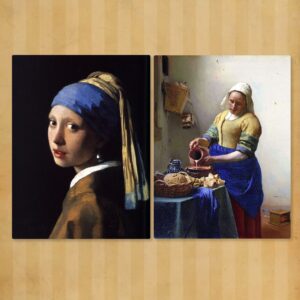

フェルメールはカメラ・オブスクラで見たままに錯乱円を描いていたわけではない。錯乱円が生じるのは陽射しを受けてきらきらと輝く表面だけだが、フェルメールはそれ以外の部分にも自由に光の粒を描いた。《デルフトの眺望》の影の濃い部分や、《牛乳を注ぐ女》のパンと《レースを編む女》の糸のように光を反射しない、光沢のないものにもつかっている。こうした光の粒のつかい方は写実的ではなく、むしろ錯視的表現だと言える。光沢のないものの表面は実際には光を反射しないが、光の粒をつかって反射するように見せることで、逆にリアル感を演出しているのだ。

フェルメールは自然界をカメラ・オブスクラで観察し、その光と影、そして色彩と色調について学んだ。しかしカメラ越しに見たものを、盲従的にそっくりそのまま描いたわけではなかった。

ダ・ヴィンチはこんなことを言ってる。「学んできたことやその眼で見たものを、何も考えずにそのまま描く画家は鏡と同じだ。鏡は自分が何を映しているのか知りもしないし、知ろうともせずに、ただ眼の前にあるものを映しているだけだ」どうやらフェルメールはこの言葉を座右の銘としていたとみえる。フェルメールは光学原理にきわめて忠実になることもあれば、それを無視して自分の表現したい構図と伝えたい感情や情感に合わせることもあった。(中略)

その一方で、フェルメールはまさしくカメラ・オブスクラの画像を描き写していたとする声もある。カンヴァス上に直接投射して、そのままなぞっていたというのだ。研究家のピーテル・スウィレンスは一九五〇年の著書で、フェルメールの作品の何点かはカメラ・オブスクラの画像をなぞったものだと主張した。

その二〇年後、今度はダニエル・フィンクが一六五七年以降の作品のほぼすべてに当たる二七点の作品がカメラ・オブスクラの画像をトレースしたものだとする説を打ち出した。

近年ではフィリップ・ステッドマンが二〇〇一年の著書『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』(鈴木光太郎訳、二〇一〇年、新曜社)で、一六五七年頃に突如として遠近法が洗練され、さまざまな光学的な特徴も見せるようになったことから、フェルメールは部屋型カメラ・オブスクラでカンヴァス上に映し出した画像をトレースするようになったと見てまちがいなく、そうやって描いた作品は一〇点にもなると述べている。

このステッドマンの分析は、発表以来フェルメールを巡る論争で大きな影響力を持ち続けている。このステッドマンの主張を少し掘り下げてみよう。

原書房、ローラ・J・スナイダー、黒木章人訳『フェルメールと天才科学者 17世紀オランダの「光と視覚」の革命』P212-215

※一部改行しました

この引用箇所の最後の方に出て来たのがまさに今回紹介しているステッドマンの『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』になります。

ローラ・J・スナイダーは次のようにステッドマンに反論しています。全てはご紹介しきれませんので抜粋して引用します。

ステッドマンはその一〇点を集中的に論じた。それらはどれも同じ部屋で描かれたかのように見え、床にしてもパターンこそちがうものの、どれも白と黒の大理石タイル張りだ。見る側から見て左側に開き窓があるのも同じだ。一〇点すべての作品に描かれている大理石タイルを、どれも標準サイズの一辺が二九・三センチメートルのものだと仮定すると、部屋の大きさがわかってくるとステッドマンは言う。

次に彼はそれぞれの作品の〝理論上の視点〟、つまりそこから見なければ描かれた光景どおりには描けない位置を特定した。各作品に描かれているものは全部、視点を頂点とする〈視覚のピラミッド〉のなかになければならない。

そしてそのピラミッドの頂点から伸びる四本の線が背後の壁と交わってできる四角は(つまりピラミッドの底面は)、一〇作中六作がその絵のサイズとほぼ一致するとステッドマンは主張する。この〝驚くべき幾何学的一致〟は、ステッドマンによれば、たったひとつの仮説で説明がつくというー部屋型カメラ・オブスクラをつかってカンヴァスに画像を投影し、その輪郭をトレースしたからだ。

このステッドマンの分析はさまざまな意味で名人技だと言える。それに何よりも彼は、フェルメールはカメラ・オブスクラを何らかのかたちでつかっていたという事実を、多くの人々と美術史研究者たちに知らしめ、関心を向けさせた。

しかしフェルメールの絵が伝えることをそっくりそのまま解釈し過ぎた結果、ステッドマンの研究はおかしな方向に進んでしまった。

絵画とは時代を映し出す鏡であり、とくに一七世紀はその傾向が強かったのだが、その一方でそうした絵を当時のネーデルラントの生活を正確に描写したものとして、そのまま読み解けばいいというものでもない。

たしかにフェルメールがこの一〇点の絵を制作したのは、義母と同居していた家の二階のアトリエだったと見てまちがいない。しかしそのアトリエの光景を、フェルメールはそっくりそのまま写実的に描いた、とするのは早計だ。

フェルメールは二階にあったアトリエを見たままそっくりに描いたのではないということは、白と黒の大理石タイルを見ればわかることだー彼のアトリエにそんなものを敷くのは不可能だったのだ。

当時の個人宅の室内画の多くに白と黒の大理石タイルが描かれているが、そうした絵は実際の光景をそのまま描写したものではない。一七世紀当時、大理石タイルは高価で、おもに公共の建物に威厳を与えるためにつかわれていた。それ以外の建物でつかわれた数少ない例のひとつが、デルフトの隣の都市レイスウェイクにあったオラニエ公の邸宅で、いくつかの部屋に敷かれていた。

デルフトの裕福な商人たちの家であっても大理石タイル張りの床はめったになく、あったとしても客を歓待する玄関広間ぐらいだった。寒冷で湿気の多い気候のネーデルラントでは足の裏に心地よい木張りの床が好まれ、最富裕層ですら居住部分には大理石ではなく木材を敷いた。(中略)

フェルメールのアトリエに高価な大理石タイルが敷かれていたはずがなかった。家の主の、稼ぎの悪い義理の息子が使う部屋となればなおさらだ。つまり、実際には敷かれていなかった正方形のタイルを基準にしてフェルメールのアトリエを〝測量する〟ことに何の意味もないということだ。

さらに言うと、ステッドマンの主張する、フェルメールの視点を頂点とする〈視覚のピラミッド〉と背後の壁が交わってできる四角のサイズが六点の作品で一致するという、〝驚くべき幾何学的一致〟を論理的に説明し得る唯一の説は誤解を招きかねないものだ。実際には、六点のうち五点が絵そのもののサイズもほぼ同じで、その差は縦横で三センチメートルほどしかない。さらにもうひとつ言えば、フェルメールは標準サイズのカンヴァスをつかっていたのだ。そのカンヴァスに合わせるようにアトリエを描いたのだとしたほうが納得がいく。

原書房、ローラ・J・スナイダー、黒木章人訳『フェルメールと天才科学者 17世紀オランダの「光と視覚」の革命』P215-218

※一部改行しました

そしてスナイダーはこの直後に非常に重要な指摘をします。

フェルメールは、ただ闇雲にカメラ・オブスクラの画像をなぞって絵を描いていたわけではない。かと言って、カメラ・オブスクラが絵を描く道具として役立つものなのかどうか、あれこれ確かめようとしていたとか、あれこれ想像を巡らせる必要もない。

確かなことはただひとつ、フェルメールは自然哲学者のようにカメラ・オブスクラをつかって光の実験をして、光の特性を究明しようとした、ということだ。その真の目的は〝見せかけの現実〟、つまり今で言うところの〈仮想現実空間〉を創り出す技を習得することにあった。そしてそのVR空間を本物のように見せる手練手管を身につけようとしていたのだ。

フェルメールは実験を通じて視覚という概念を究明した。レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチの教えを忠実に守るには、フェルメールはレーウェンフックと同じように、〝見るための修行〟を積まなければならなかった。フェルメールを頂点とする一七世紀ネーデルラントの画家たちは、光学機器の力を借りて見るための修行を積むようになった。そしてそのもの自体が絵画である視覚を、絵具という言葉に翻訳し、カンヴァスに表現する技を身につけるようになったのだ。

原書房、ローラ・J・スナイダー、黒木章人訳『フェルメールと天才科学者 17世紀オランダの「光と視覚」の革命』P219-220

※一部改行しました

「フェルメールはレーウェンフックと同じように、〝見るための修行〟を積まなければならなかった。」

私はこの言葉を読んでふと仏教のことを連想してしまいました。

仏教もまさしく、ブッダの言葉を深く学び、それを体得することによって「世界を新たな眼で見ていこうとする歩み」であります。そのために仏道に生きる者は「修行」をするのです。

私たちは「世界を見ている」ように思えても、実はその姿を全然見れていないのです。いかに私たちが漠然と世界を見ているか。いかに自分の見たいように見ているか。これはなかなか自分では気づくことができません。

だからこそレーウェンフックやフェルメールのように道具を用いたり、仏道修行者のように日々鍛錬をすることで〝見るための修行〟を積むのです。

これは非常に興味深い指摘であるなとこの本を読んで思ったのでした。思わぬところで仏教との類似点を感じ、胸が熱くなる思いでした。

さて、ローラ・J・スナイダーはこのように『フェルメールと天才科学者 17世紀オランダの「光と視覚」の革命』でステッドマンの説を批判するのでありますが、私は専門家ではないので結局どちらが正しいのかはわかりません。個人的にはスナイダーの見解の方が説得力があるなと感じているのですが、その辺りは専門家の判断に委ねたいと思います。

いずれにせよ、ステッドマンの『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』では、私が知りたかったカメラ・オブスクラについて詳しく知ることができました。これは私にとっても非常にありがたいものでありました。

フェルメールが用いたこの光学機器についてより知りたい方にはぜひおすすめしたい作品となっています。

以上、「F・ステッドマン『フェルメールのカメラ 光と空間の謎を解く』写真機の先祖カメラ・オブスクラとは何かを知るのにおすすめ!」でした。

Amazon商品ページはこちら↓

前の記事はこちら

関連記事

コメント