Table of Contents

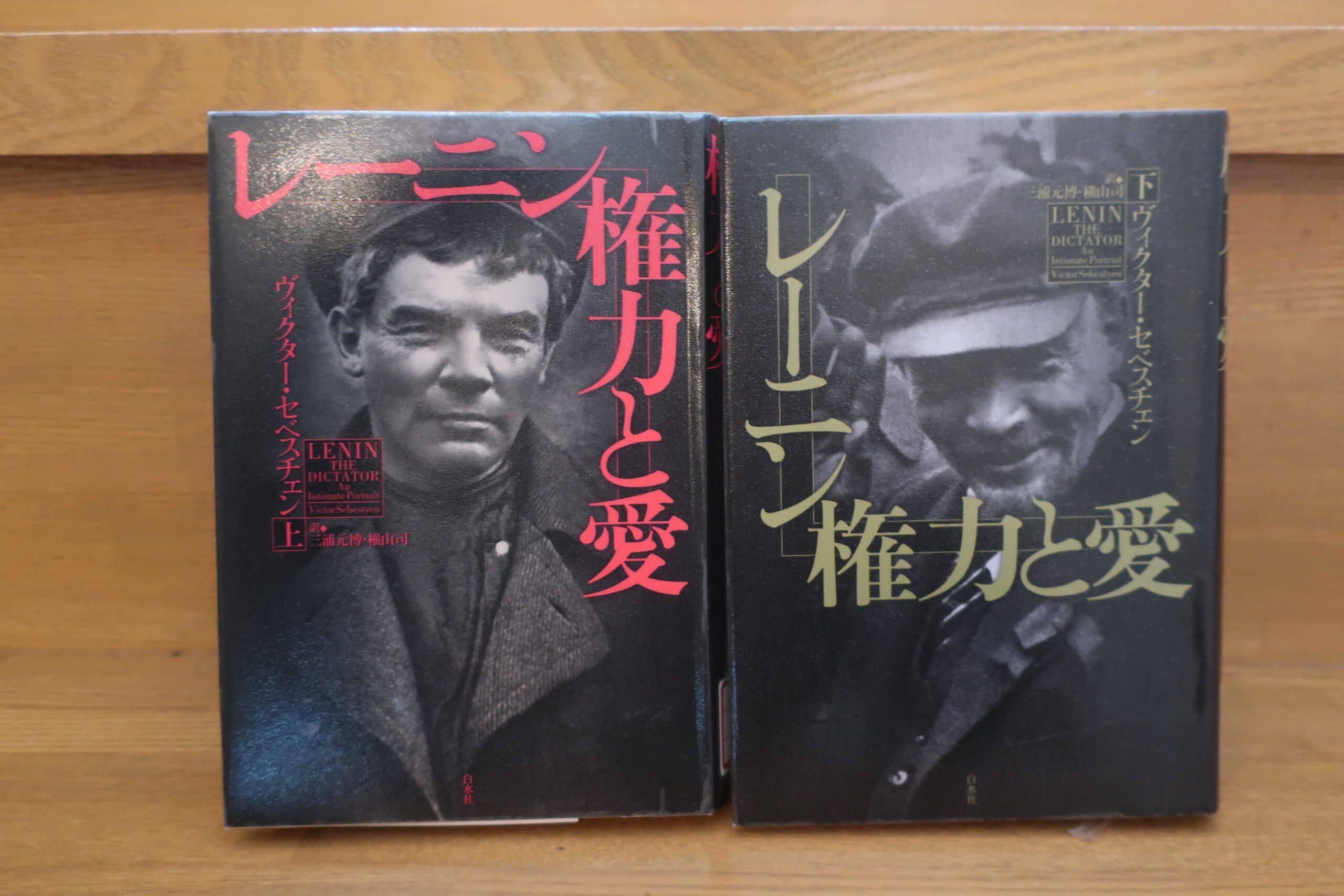

Read Victor Sebeschen's Lenin, Power and Love (12)

Continued by Victor SebeschenLenin, Power and Love.The following are some of the memorable passages from the

Transfer of the capital from St. Petersburg to Moscow

In March 1918, World War I was still raging and the Germans were closing in on the capital, St. Petersburg (Petrograd).

Lenin therefore decides to move the capital to Moscow.

Most of the old Bolsheviks viewed Petrograd as a Western city with European traditions, while Moscow, with its onion-roofed churches, was considered the capital of "Old Russia" with its half-Asian Orthodox faith.

For many, moving to his land seemed like a step backward, implying insulation from the roots of European socialism. Trotsky said that Moscow, with its "medieval walls and a frightful number of gilded cupolas, was a complete paradox as a bastion of revolutionary dictatorship."

Others in the Bolshevik leadership said that walking away would seem like "cowardice" and an ethical defeat. The Bolsheviks should consider the "glorious spirit of Smolinui," they said.

Lenin dismissed their arguments. If government moves, power and authority move with it, he said.

If Germany invades Petersburg [he almost always called it by its name or "Pieter"] and all of us in a massive raid, the revolution will collapse.

If the government is in Moscow, the fall of Petersburg is but one blow, albeit a grievous one. If we stay, we will increase the ...... military danger. If we leave for Moscow, the temptation for Germany to take Petersburg will be much smaller.

What would be in their interest in taking a starving revolutionary city? ....... Why do you all engage in childish chatter about the symbolic importance of Smolinui? Smolinny is the place to be with us. If all of you were in the Kremlin, all of your symbols would be in the Kremlin."

Hakusuisha, Victor Sebeschen, translated by Motohiro Miura and Tsukasa Yokoyama, Lenin: Power and Love, vol. 2, p. 184

Some line breaks have been made.

It was only with the relocation of the capital that Moscow has remained the capital of Russia to this day. As the former capital, Moscow once again reigned as the center of Russia.

For more information on the history of St. Petersburg and Moscow, please see the following article previously published.

Food Crisis of 1918

Most of Russia was starving - so Lenin had to find someone to blame. No matter what misery and bloodshed would be inflicted on Russia's thousands of villages, sacrificing the peasants would be the quickest way to feed the country. Lenin thought so from the beginning. The Bolsheviks did not directly cause the food crisis. The breakdown of order caused by the war, a completely broken transport system, and a bad harvest were some of the causes. But Lenin's punitive policy of coercion and brutal terror made matters worse. (omitted)

Food shortages became even more severe during 1918, with the most severe effects on urban areas. One reason was that the transportation system was so poor that distribution was a major problem, and another was inflation.

After the revolution, currency quickly became worthless, and peasants refused to accept payment in cash. The number of employees at the mint went from about 300 in 1917 to 13,500 a year later. Sukhanov was not kidding when he said, "Banknote printing was the only growth industry."

Within a year, the total amount of rubles in circulation jumped from 600 billion to 225 billion. A complete parallel system of payment and barter was created. Some Bolsheviks, experimenting with imaginary socialist economic theories, thought inflation was a good thing because it destroyed the economy's dependence on currency. Lenin disagreed, realizing how it would affect the value of everything, but like many leaders throughout history, he was helpless once inflation began to take hold.

Hakusuisha, Victor Sebeschen, translated by Motohiro Miura and Tsukasa Yokoyama, Lenin: Power and Love, vol. 2, p. 188-189

Some line breaks have been made.

The First World War and the Revolution had devastated the countryside, and the transportation system had collapsed, so the food situation in Russia was already perilous. A bad harvest was also threatening the country's food supply.

Lenin, who came to power, was already at a critical juncture.

So Lenin took the method of forced food requisitioning.

Lenin's Answer to the Food Crisis: Forced Conscription and Terrorism

Lenin needed an enemy. So he created a new class of Russian "kulaks," or rich peasants, who, he argued, were hoarding grain and deliberately starving the rest of the country, especially the cities.

In reality, there were few wealthy peasants in Russia. A few owned substantial land, some lent money to other farmers, and a few owned more than one horse, ox, or hoe. Less than two percent of the farmers employed someone other than family members. Lenin's political campaign against the rich peasants was an extension of the class war he was waging in the cities. (omitted).

The peasants were coerced, threatened, and eventually terrorized into submission. Originally, most of those who were considered wealthy farmers were either village elders or leaders of rural communities. Or they were the most successful, inventive, or very hard-working farmers.

Hakusuisha, Victor Sebeschen, translated by Motohiro Miura and Tsukasa Yokoyama, Lenin: Power and Love, vol. 2, p. 188-189.

Some line breaks have been made.

Lenin uses his best tactics to defuse the crisis.

It is a method of "creating enemies, inciting hatred among the masses, and using violence."

Even though there was no actual class of wealthy farmers (kulaks) in Russia, they touted their existence. Most of them, as was quoted, "were mostly village elders or leaders of rural communities. Or they were the most successful, inventive, or very hard-working farmers". They were to be accused and attacked on unprovable charges.

Lenin's answer to the food crisis was to intensify coercion and terror. In the early summer of 1918, he invoked the "war for grain" in a bloodcurdling speech, blaming the rich peasants and "unjust profiteers" for the famine in Russia.

The "rich peasants are the violent enemies of the Soviet government. ...... These vampires were made wealthy by the starvation of the people. These spiders were fattened by the workers. These leeches sucked the blood of the workers and grew richer while the city workers starved. Ruthless war on the clerics! Death to them all!"

Hakusuisha, Victor Sebeschen, translated by Motohiro Miura and Tsukasa Yokoyama, Lenin: Power and Love, vol. 2, p. 191

Some line breaks have been made.

The reality of the "fight for grain" - Harsh grain collection

In the first month of the proclamation, so-called "conscripts" were sent to more than 20,000 villages. The requisition teams usually consisted of 75 men and two or three machine guns, who would surround a village and demand that a certain yield of grain be handed over, as determined by the local Bolshevik party headquarters.

Lenin's edict declared, "Any speculator who is caught red-handed without offering the required quantity of grain, and who can be convicted on the basis of clear evidence, will be executed on the spot."

The commandos usually acted with extreme brutality, always torturing suspects until they found the "right" amount of grain. One Bolshevik official was shocked to witness conscripts raiding a village in the "black soil zone" of southern Russia. The "means of deprivation remind one of medieval inquisitions. They strip peasants naked, make them kneel on the ground, whip them, beat them, and sometimes kill them."

Lenin himself recommended additional innovations in the "class war in the villages". Whenever punishment is inflicted, the disciplining squads "should always call at least six witnesses, chosen from the poor inhabitants of the neighborhood. In some cases, the requisitioning units would hold 20 or 30 villagers hostage until the required amount of grain was handed over to them.

Originally, Lenin had insisted that all peasants deliver grain individually and that those who did not be "shot on the spot," but this idea was flouted by the People's Commissars for Food, Aleksandr Tsurupa and Trotsky, who had to soften the tone somewhat. The result was that peasants who "fail to deliver to the properly designated railroad stations and shipping points" "shall be declared enemies of the people."

Hakusuisha, Victor Sebeschen, translated by Motohiro Miura and Tsukasa Yokoyama, Lenin: Power and Love, vol. 2, p. 191-192

Some line breaks have been made.

Grain requisitioning was extremely harsh. I won't go into the details in this article, but the following book, which I previously mentioned, describes the Soviet Union during this period in considerable detail.

Lenin, who had implemented a rather harsh forced requisition in 1918, would later implement an even more disastrous policy in 1921.

The deprivation at this time resulted in a huge number of starvation deaths.

And Soviet food policy was carried over into the subsequent Stalin era, leading to a catastrophe in the 1930s in which millions starved to death.

be unbroken

Next Article.

Click here to read the previous article.

Click here for a list of "Reading Biography of Lenin" articles. There are 16 articles in total.

Related Articles