Table of Contents

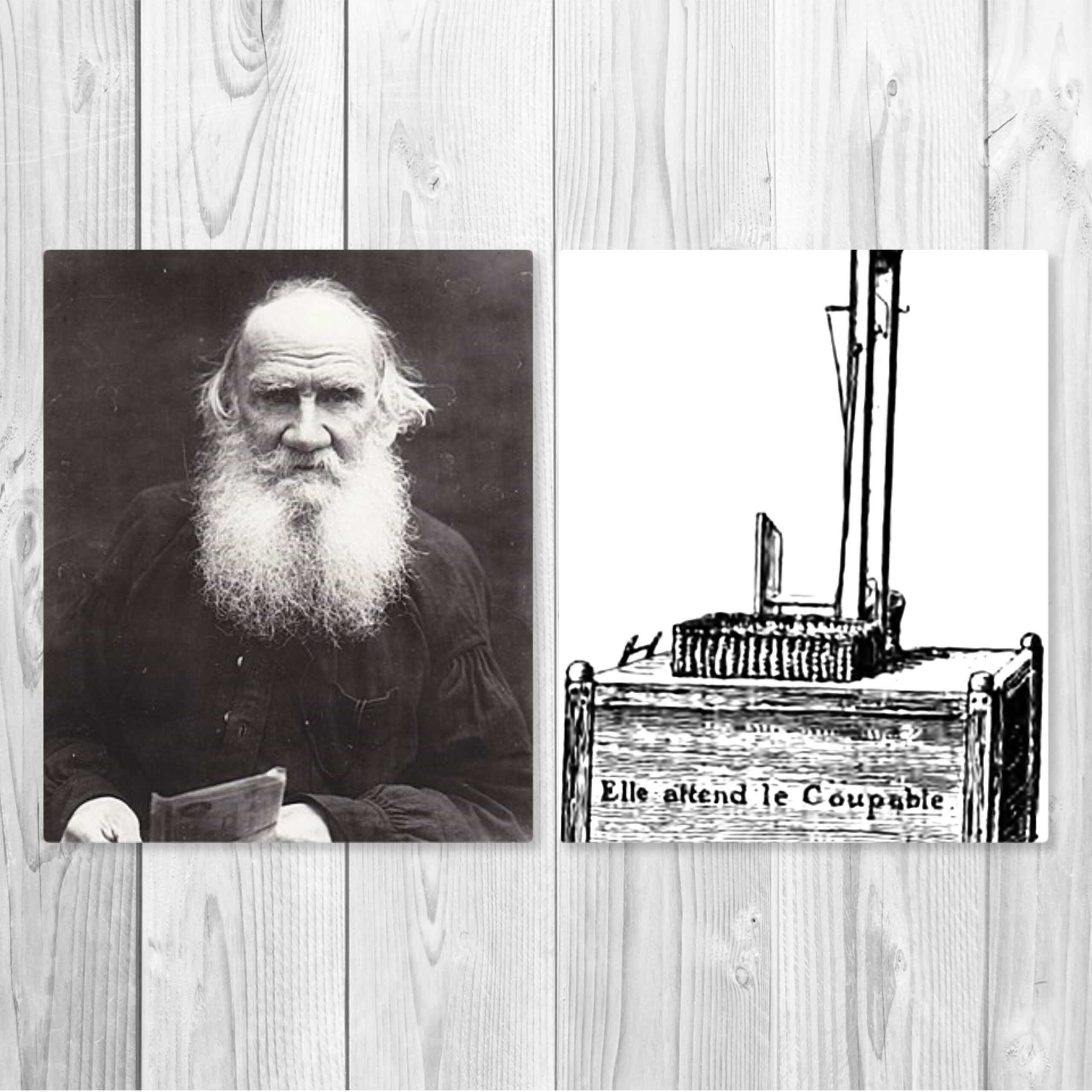

Tolstoy shocked to see guillotine execution in Paris - source of nonviolentism and common ground with Hugo and Dostoevsky

So far in this blog we have talked about Tolstoy's Kafkaesque experience.

In his later years, Tolstoy began to preach a thoroughly nonviolent approach. This was triggered by his military experiences in the Kafkaes and the Crimea, as well as "an experience" in Paris, which we will introduce here.

Tolstoy returned to Moscow after the Crimean War and was hailed by the literary world as the "new great writer. However, during his days in Moscow, Tolstoy came to dislike the intellectuals and aristocrats of the Russian literary world and the upper class. At this point in his life, Tolstoy's hatred of civilization, which had continued since "War and Peace," began to grow stronger.

In 1857, with these thoughts in his mind, he left Russia for Paris.

This Tolstoy's First Trip to Western Europe by Takashi FujinumaTolstoy."In the following paragraphs, it is explained as follows.

Purpose of travel to Western Europe

In January of 1977, shortly after his peasant emancipation and marriage ended in disappointing results, Tolstoy made his first trip to Western Europe. In 60-61, he made a second trip to Western Europe, but while he had a number of specific objectives for that trip, he had no clear objectives for his first trip. Some explain that he went abroad to heal the wounds of his frustrated emancipation of the serfs and his failed love affair with Waleria, but this is not the case. When Tolstoy returned to Russia from Sevastopol, he already had a wish to go to Europe for about seven months, and he had notified the military of this wish.

The first possible reason is to see for himself the reality of the British and French defeat of Russia. After returning to Russia after the defeat, Tolstoy was almost drowned in the wave of Progress beliefs. He was confronted with the tendency to believe that England and France had not only defeated Russia with more advanced weapons than Russia, but were also role models for Russia's future. If this is the case, I must go to Western Europe and see what Russia will look like ten or twenty years from now. Tolstoy probably had such feelings, but it seems that he also meant it as a recreational trip to wash off the grime of four and a half years of life on the battlefield.

At least, his behavior during the trip shows that he was not so tense or busy as to be on an inspection tour, a field trip, or running around Western European countries, but rather he wasted his time sparingly. Moreover, deep down in his heart, Tolstoy did not consider Western Europe as a role model, nor did he consider Western life as the future of Russia.

The British and French I saw in the Crimean War were no less brutal killers than the Russians, and yet they were proud of it. I am not inclined to follow the example of such people. When Tolstoy went out to Western Europe, he did not want to look at Western Europe in a calm and objective way, but rather he wanted to find evidence that Western Europe could not be a model for Russia.

Dai-san-bunmeisha, Takashi Fujinuma, Tolstoy, p212-213

Some line breaks have been made.

It even seems to me that when Tolstoy went out to Western Europe, he was not so much trying to look at the West dispassionately and objectively, but rather to find evidence that the West could not be a model for Russia."

I think this is a very important point.

We will be looking at Tolstoy's situation in Paris later, but I hope you will keep this in mind.

What was Tolstoy doing in Paris?

Tolstoy crossed the border on January 29, 1957, in a new type of fast mail coach, and arrived in Paris on February 9 (21st according to the European calendar, or the Gregorian calendar currently in use in Japan). Paris seemed to be his first destination, and he easily passed through Warsaw and Berlin on the way. As soon as he arrived, he rented an apartment, which was probably quite expensive, and stayed in Paris for about a month and a half until March 27. This was quite a long stay for a traveler.

During this period, Tolstoy "devoted most of his time to scrutinizing the new surroundings of life with his characteristic insatiable curiosity," and some have listed his visits to the Louvre, the Palace of Versailles, Notre Dame Cathedral, the Academy, and lectures at the University of Paris.

However, a modern tourist can visit the Louvre in a day. Moreover, in his later years, Tolstoy made a cold comment about the Louvre Museum, which he visited three times with the greatest interest, saying, "Except for the old sculptures, I have no impression of the museum. It is also known that Tolstoy met with various famous people and literary figures, but they only exchanged greetings in the salon and never had a meaningful conversation.

According to his diary, Tolstoy's daily routine in Paris consisted of sleeping in the morning until he wanted to get up (it was not unusual for him to sleep all morning), going out in the afternoon, meeting Turgenev, who was living in Paris at the time, almost every day, and sharing meals with him. Even if he occasionally met someone other than Turgenev, it was almost always a Russian. In the evenings, we usually went to the theater or hall to see a play or listen to music. Sometimes I would go out to social occasions, and in such places I also socialized with French people.

However, I had never walked around Paris, and even though I could speak French freely, there was no trace of any coherent conversation with French writers or artists, much less meeting and chatting with ordinary citizens. He was not in good health and did not have much energy.

To put it in a somewhat exaggerated and mean-spirited way, "going to bed in the morning, chatting with Russians, and going to the theater in a random manner" was the basic pattern of Tolstoy's daily routine during his stay in Paris. His diary also reads, "Woke up at 0:00. Woke up at 00:00, went out for dinner with Turgenev at 00. He wrote travelogues for two days in Switzerland, but other than that, he did not write any travelogues during or after his return to Japan.

A few years later, in the year 62, Dostoevsky also traveled to Western Europe. In two and a half months, he traveled to Berlin, Dresden, Cologne, Paris, London, Lucerne, Geneva, Florence, Milan, Vienna, and other cities. After returning to Japan, Tolstoy wrote a travelogue entitled "Impressions of Summer in Winter" (known in Japan as "Natsu Zou Fuyu Ki"), in which he clearly expressed his views on Western Europe, saying, "I have nothing special to say to you, my readers, much less write about it in an orderly fashion. Compared to this, Tolstoy's travels are much less impressive.

Nor can it be compared to Nikolai Karamzin's carefully prepared and content-rich trip to Western Europe, the basis of his masterpiece of travel writing, "Letters of a Russian Traveler". And that is not all. Tolstoy himself had a specific theme of educational research when he made his second trip to Western Europe from June 1960 to April 1961, and he energetically researched and studied the actual conditions in Western Europe, publishing the results in a number of articles. Only on the first trip, Tolstoy was slow to react and lacked energy.

Dai-san-bunmeisha, Takashi Fujinuma, "Tolstoy," p. 213-215.

Some line breaks have been made.

It is surprising that Tolstoy, with his uncanny insight, spent his days in Paris in a daze, given our image of him.

It was also surprising to learn that he met with Turgenev every day during this Parisian life.

And what impressed me here was the presence of Dostoevsky.

In this work, Dostoevsky thoroughly criticizes Western civilization. This work is very important in understanding Dostoevsky's view of the West, and it had a great influence on his thought in his later years.

A writer as good as Tolstoy could have left some works, just as Dostoevsky did at this time. But he did not. What does this mean? The author states that it has something to do with "an event" that will be discussed next.

The Impact of the Guillotine Execution in Paris

During the forty-six days that Tolstoy was in Paris, there was only one day when he became active and excited. It was on March 25.

That morning Tolstoy woke up at seven o'clock. During his stay in Paris, he had never gotten up earlier than 8:00 a.m., and usually between 10:00 and 12:00 a.m. This day was an exception. This day was an exception. In addition, the night before he had gone to a shady "magic theater" and had eaten somewhere else (apparently, also a shady place), returning home at 2:00 am and going to bed at 3:00 am. And even though I usually stay at home until past noon after getting up, I went out right away, even though I felt like I was sick with a hangover or something that day.

The destination was the square in front of the prison. It seems that Tolstoy had heard from someone or read in the newspaper that the execution was to be held there that morning, so he went to see it. Tolstoy himself has never told us why he went to the trouble of getting up early, which is not his favorite thing to do, and why he went to such a place even though he was in poor health.

According to newspaper articles of the time, a crowd of 12,000 to 15,000 people gathered, including a considerable number of women and children. Torches were burning everywhere, and the sound of street vendors selling food and liquor could be heard. The people were all looking forward to seeing the murderous criminal who had committed two robberies and murders, and who was now being held in the city.decapitatorThe public gathered to watch the public executions by the "death squads". The best places with the best view of the execution were taken early, so the enthusiasts came the night before and stayed up all night. Tolstoy took the best spot right in front of the guillotine. Perhaps he had sent someone to get a spot the night before.

Soon the condemned man was drawn out and executed. Tolstoy saw before his eyes the head of a living person plunged into the hole of the guillotine, the blade of sturdy, sharp steel falling from above, and in an instant, the head was cut off and dropped into the box. He had seen many gruesome deaths on the battlefield, and he depicted these hellish scenes realistically in works such as "Sevastopol in December" and published them in the public domain. However, the almost bloodless death of a single person had a greater impact on Tolstoy than the mass slaughter on the battlefield. The moment he saw it, his hair literally stood on end. That night he could not sleep well, and when he thought he did, the guillotine appeared in his dreams.

He immediately wrote a letter to his friend Boatkin to inform him of the death penalty and to express his feelings: "If there is a moral code that lets me go forward without anyone forcing me to do so, I can understand it. I can understand a moral code that lets me go forward without anyone forcing me to do so, and I can sense a code of art that always gives me happiness. But the political code is so horribly false to me that I cannot judge whether it is better or worse.

Moreover, the horror of that day was so deeply etched in his memory that in his "Penance," written twenty-five years later, he described the experience as vividly as if it had happened only yesterday, writing that the moment he saw the head chopped off, he "knew with my whole being, not with my head, but with my heart, that it is not what people say or do that determines what is good and what is necessary, but what I am. I realized, not with my head, but with my whole being, that it is I, with my heart ......, who decides what is good and what is necessary.

War is violence and madness. One may have no choice but to take it for granted that blood will be spilled and people will die in the midst of it. But this is Paris, the city of flowers, where the best of European culture is gathered. Moreover, in the midst of a happy and orderly life, murder is committed by law and reason in order to protect that happiness and order. And when the public sees this, at least a fraction of them must feel a sense of satisfaction that the bad guy "got what he deserved.

Peaceful, happy, and civilized nations ultimately protect their own interests, which they call "public order and morality," with the same murder and violence as in war. For Tolstoy, this was more frightening than war, which laid bare inhumanity. Many Russians say that the West is their goal. However, as a result of "progress," society and order have grown so large that there is a growing danger that a person's life, feelings, aesthetics, and love will be trampled underfoot. Tolstoy believed that the death penalty illustrates this point.

Two days after his execution, Tolstoy abruptly left Paris and went to Geneva. It was as if to say, after seeing the brutal execution and having caught the tail of France, which is said to be a model of progress but is in fact the devil, he had no more use for Paris. He wrote to Turgenev from Geneva about Paris, which had allowed him to enjoy a carefree atmosphere of freedom, saying, "I am glad I left such a sinful city as Sodom.

Tolstoy's behavior at this time was like a ravenous beast that happened to attack its prey, which it then nipped and left quickly and with great gusto. If so, was the beast of prey in Paris for a month and a half in order to ambush its prey? And was the greatest achievement of Tolstoy's stay in Paris to see the death penalty and determine that it was the true face behind civilization?

Dai-san-bunmeisha, Takashi Fujinuma, Tolstoy, p. 215-218

Some line breaks have been made.

Tolstoy left his usual pattern of behavior.expresslyHe was there to witness the execution.

And what he saw there had a tremendous impact on him.

The last part of this quote,

Tolstoy's behavior at this time was like a ravenous beast that happened to attack its prey and then quickly and triumphantly snatched it up and left the scene. If so, was the beast of prey in Paris for a month and a half in order to ambush its prey? And was the greatest achievement of Tolstoy's stay in Paris to see the death penalty and to determine that it was the real face behind civilization?"

I think it is very significant to point out that I am not sure what Tolstoy was really thinking at that time. However, I thought this view by an expert who has studied Tolstoy for many years was very interesting.

In fact, when I read Tolstoy's life and works, I feel that this point is indeed the very heart of the matter.

And as the title of this article suggests, French writer Victor Hugo was similarly strongly influenced by executions.

Hugo, too, was shocked to see executions and torture by public authorities, and later painted a work in which he spoke out against the death penalty. That is the link above.The Last Day on Death Row.will be.

Even more intensely, Dostoevsky had the extreme experience of being pardoned shortly before his own execution after being sentenced to death. Although this pardon was preordained, Dostoevsky had no way of knowing that he was on the verge of death.

The experience was his masterpieceThe Moron.The story is told through the mouth of Myshkin, the protagonist of the

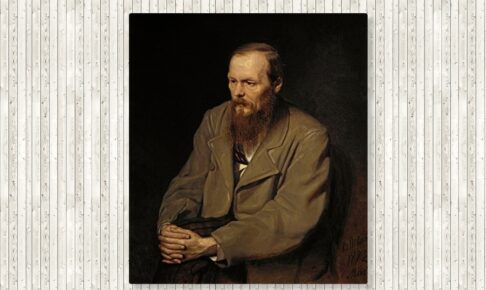

Tolstoy, Hugo, and Dostoevsky, three of the greatest writers of 19th century Europe.

I find it very interesting that these three have "capital punishment" in common.

Tolstoy left Paris immediately after seeing the guillotine execution and headed for Switzerland.

Then, in Lucerne, Switzerland, he encountered a further incident. The incident made Tolstoy completely lash out against Western civilization.

The story of how this happened is described in "Lucerne," which will be introduced in the next article.

Tolstoy's first trip to Western Europe was a journey that fostered a sense of "hatred of the West.

The above is "Tolstoy Shocked to See Guillotine Executions in Paris - The Source of Nonviolentism and Commonalities with Hugo and Dostoevsky".

Next Article.

Click here to read the previous article.

Related Articles