スリランカには本当にカースト問題はなかったのだろうか~インドとの違いや内戦、宗教との関係は

【インド・スリランカ仏跡紀行】(47)

スリランカには本当にカースト問題はなかったのだろうか~インドとの違いや内戦、宗教との関係は

前回の記事「(46)キャンディのペラデニヤ大学で1971年のマルクス主義学生による武装蜂起について考える」で1971年のマルクス主義学生による武装蜂起についてお話しした。

この武装蜂起は単にマルクス主義的な側面からなされたのではない。実はこの武装蜂起にはスリランカに根深く存在していたカーストの問題も大きく関わっていたのである。

当時のスリランカは大学卒業者でも就職難の時代だった。大都市以外の村の若者達も大学進学する時代になったはよいものの、就職先もなく村に戻ってくるということが頻発していた。親が苦労して学費を捻出してもそれが実を結ばない事態に陥っていたのだ。

大学に進学して一生懸命勉強してもすでに高給の仕事は上流階級ががっちり抑えてしまっている。自身の能力がいかに高かろうと、カーストや縁故がなければ就職できないのが常態化していたのだ。特に地方の村ではそれが顕著だった。いかに大学で勉強しようと縁故がなければどうしようもないのである。こうした状況に若者たちが不満を募らせ、それが爆発したのが1971年の武装蜂起でもあったのである。

この辺りの葛藤がまさにエディリヴィーラ・サラッチャンドラの『明日はそんなに暗くない』で描かれている。

今回の記事ではこうしたスリランカにおけるカーストの問題について少しだけお話ししていきたい。これはスリランカだけの問題ではなく、私達日本人にも関わる問題だと私は思うのである。

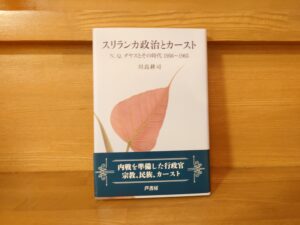

今回の記事では川島耕司著『スリランカ政治とカースト—N.Q.ダヤスとその時代 1956~1965―』を見ながらこの問題についてお話していきたい。

では、さっそく始めていこう。

スリランカ社会のもつ明確な特徴の一つは、カーストに言及すること自体が強力なタブーであることである。カーストはセンシティブな話題であり、日常会話のなかでは極力回避され、公的な議論のなかにもほとんど登場しない。

スリランカ政治においては、個人の権利、女性の権利、あるいはエスニック・マイノリティの権利という議論は登場するが、マージナルな地位におかれたカーストに属する人々の権利という概念はほぼ存在しない。

逆に、カースト間の平等に関する問題を提起しようとする試みはしばしば非難や叱責、あるいは侮蔑の対象となる。カーストを扱うことは、マナー違反であり、不必要で時代遅れであるとされる。あるいは、社会的結束への脅威であるとされ、意図的な社会的分断の手段であるとみられることさえある。

その結果、カーストに関わる問題があったとしても、著しく過小評価される。

カーストに関してはスリランカ社会は十分に平等主義的であるとされ、カーストを識別することには意味がないというのが「スリランカ全体に渡る標準的な反応」となっている。

実際、非常に頻繁にみられるのは、「スリランカのカーストはインドのそれほどは問題ではない」、あるいは「シンハラ社会においてはカーストは北部のタミル人社会ほどは深刻ではない」という主張である。

こうした反応が生まれる背景についてカンナンガラは、カーストが後進的で非近代的で抑圧的であるために、そのことに当惑する人々は無視することを好むからだと述べている。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

葦書房、川島耕司『スリランカ政治とカースト—N.Q.ダヤスとその時代 1956~1965―』P5-6

『実際、非常に頻繁にみられるのは、「スリランカのカーストはインドのそれほどは問題ではない」、あるいは「シンハラ社会においてはカーストは北部のタミル人社会ほどは深刻ではない」という主張である。』

私が今回の記事に「スリランカには本当にカースト問題はなかったのだろうか」とタイトルを付けたのはまさにこの点を強調したかったからなのである。

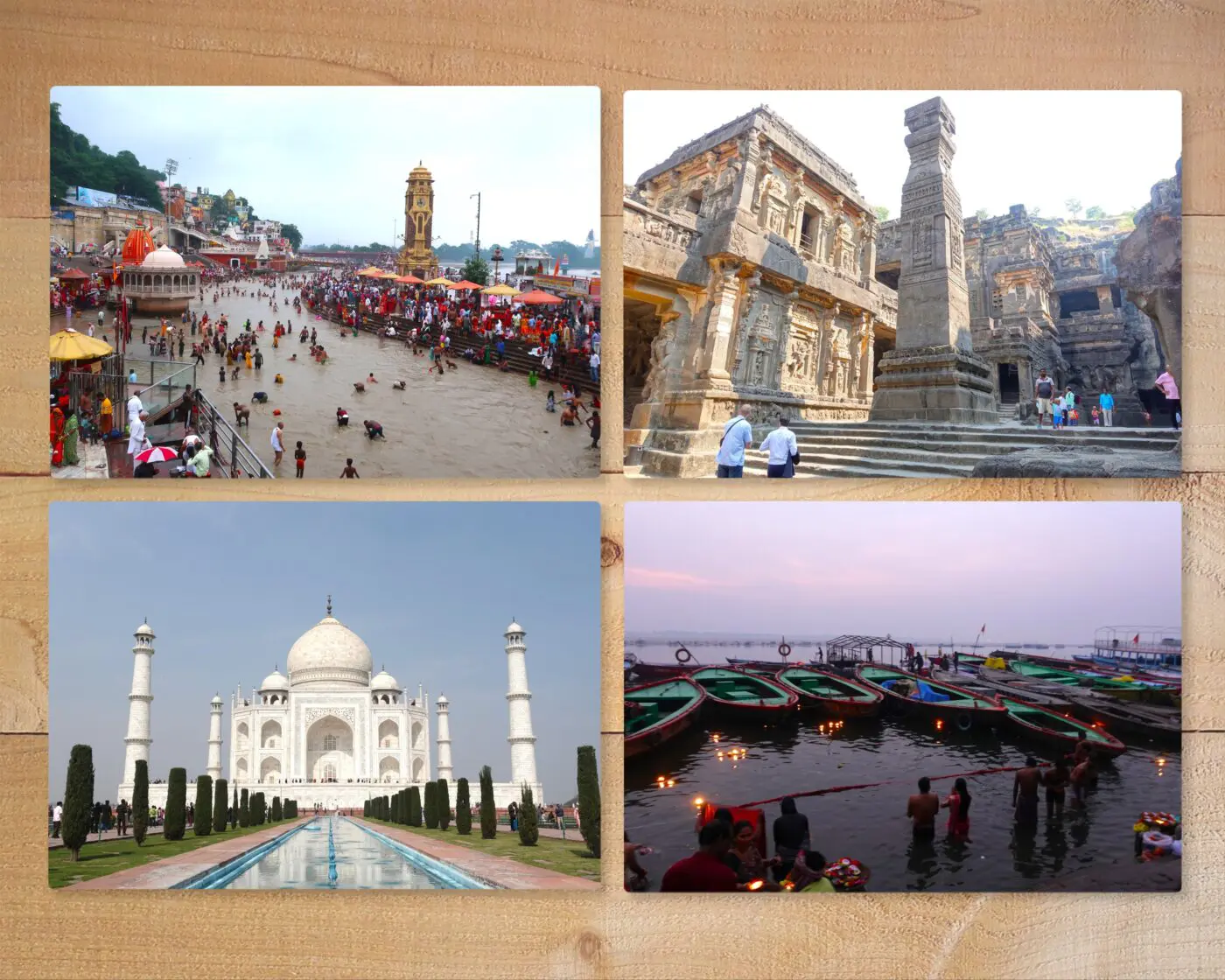

カースト問題といえば真っ先に思い浮かぶのがインドだろう。インドのカーストについては当ブログでも池亀彩著『インド残酷物語 世界一たくましい民』や藤井毅『歴史の中のカースト 近代インドの〈自画像〉』、佐藤大介『13億人のトイレ』など様々な解説書を紹介してきた。

インドのカースト差別の過酷さは私達日本人でもよく知るところである。

しかしそれに対して同じインド文化圏であるスリランカにおいてはカースト差別はほとんど問題に上がってこない。そもそも「スリランカにおいてはカースト問題はそれほどでもない」という言説すら聞いたことがない。それほど外部から「見えない」存在なのがスリランカのカーストなのである。

引き続き解説を見ていこう。少し長くなるが重要な箇所なのでじっくり読んでいこう。

しかしカーストに関わる問題が存在しないわけでは決してない。スリランカのほとんどの人々はカーストを認識しているといわれる。日常会話に出ることはめったにないが、プライベートな会話では言及されることはある。また揉め事が起きた時の罵りの言葉にも出ることもある。

結婚に関しても、かつてほど厳格ではなくなってきているが、異カースト婚をできる限り避けようとする傾向は今も存在している。新聞の結婚相手を募集する広告には今でもカースト名が記されており、カーストへの配慮に無関係な事例はわずかである。たとえば、‟Bodhu Govi”あるいは‟BG”、つまり「仏教徒のゴイガマ」として学歴などとともに自らを紹介する結婚広告は多い。

またニカーヤと呼ばれる仏教僧の集団においてもカーストが一定の役割を果たしていることは公然の事実である。低位力ーストにも得度を与えようとする動きがシャム・ニカーヤのなかにあることは確かであるが、少数派の主張にとどまっている。

低位であるとされるカーストの人々への差別や排除も明らかに問題である。スリランカでは人口の三割ほどが何らかのカースト差別を受けているといわれる。

特に非常に低いとされていたカーストに属する人々は差別、禁止、排除といった扱いを多く受けてきた。たとえ教育を受けたとしても就職には困難がつきまとい、彼らは概して非常に貧しいといわれる。

調理した食物を低位カーストの村民から受け取ることを高位カーストの仏教僧が拒否したり、子どもたちが学校において高位カーストの教員から差別を受けたりすることも少なくとも最近まではあった。

多くの子どもたちは入学によって自らが低位カーストに属していることを知るのだという。ワフンプラやバトゥガマといった中位のカーストにおいても教育や就業機会に関する不満があった。

こうした経済的に恵まれない階層におけるカースト差別に加え、経済的に富裕であり政治的にもかなりの影響力をもつエリートの間におけるカースト問題も少なくとも二〇世紀半ばにおいては重要な問題であった。

私企業においては多くの高位の役職は経営者のカーストに従う傾向があり、企業間の協力関係にはカーストが関わることがあった。政治的分野においてもエリート階層のカーストは同質化する傾向があり、地位が高くなればなるほどカーストが重要になったといわれる。政府の任用においては低位の役職ではカーストは無関係であったとしても、有力なエリートとなるとゴイガマが優勢となった。そのため非ゴイガマの間ではカーストが自らの昇進に不利に働くという不満があった。

実際、スリランカ政治においてはカーストは重要な要因の一つであった。カースト自体が政治的論点になることはなく、どの政党においても候補者がカーストを表明することはめったになかった。

しかし非公式の政治的な会話においてはカーストはきわめて重要なテーマとなった。カースト内の結束やカースト間の対立は選挙時に明らかにみられたし、政府職や入植地の配分などにおいてもカーストへの配慮がみられた。そのため、政党はその選挙区のドミナントなカーストを候補者に指名することになっていた。

その結果、チラウからタンガッラまでの南西沿岸部においては基本的に非ゴイガマが選出された。選挙区におけるカーストへの配慮は現在でも続いている。

しかし、こうした沿岸部を除けば、ほとんどの地域においてゴイガマがきわめて有利であった。実際、シンハラ人議員の圧倒的多数はゴイガマであった。たとえば、ゴイガマの議員は、一九五六年七月の選挙で選ばれた全議員のうちの五七・六パーセント、シンハラ人議員の七二パーセントを占めていた。

さらに、先にも触れたように、カーストには地位が高くなるにつれその重要性が増すという特質があるといわれる。閣僚にさまざまなカーストの者が存在してきたことは事実である。しかし首相と重要閣僚のほとんどはゴイガマであった。一般に非ゴイガマの有力者が政党の中枢にいたとしてもゴイガマであることが首相の「暗黙の必須条件」であると考えられていた。そして実際、今日に至るまでスリランカの最高権力者、つまり首相と大統領のほぼすべてはゴイガマであった。

※スマホ等でも読みやすいように一部改行した

葦書房、川島耕司『スリランカ政治とカースト—N.Q.ダヤスとその時代 1956~1965―』P6-8

いかがだろうか。私達が想像するよりはるかに根深いカースト観がスリランカにはあるのである。しかもインドに比べると外部の人間にとって明らかに可視化されにくい構造だというのも伝わったのではないだろうか。

この辺りの微妙なカースト問題について知るにはマーティン・ウィクラマシンハの『変わりゆく村』という小説をぜひおすすめしたい。

本書ではその微妙なカースト差別が多々描かれる。上の解説でも出ていたように、特に結婚を巡る問題でカーストは顔を覗かせていて、「カーストの驕り」という言葉でウィクラマシンハはそれを象徴的に描いている。

参考書だけでは感じることのできない生々しい実態を物語で知れるのが小説の素晴らしい点だ。スリランカを生活レベルでより感じられるありがたい機会となるのがこの小説である。

そして私がこの記事でスリランカの見えにくいカースト差別についてお話ししたのは他でもない。これは世界中どこにでも起こりうる問題だからだ。カースト差別というと、インドの過酷な社会問題を連想するかもしれないが、よくよく考えれば多かれ少なかれこのような階層的な階級制度は必ず存在しているのである。もちろん、日本だってそうだ。

そして1971年の武装蜂起はまさにそうしたカーストの問題が根っこにあったのである。マルクス主義は階級闘争を前面に押し出すが、それが説得力を持ったのはそれに賛同したくなる社会状況がすでにあったからこそなのである。そう考えると世界中で起きたマルクス主義の暴動についても少し違った見方ができるのではないだろうか。思想やイデオロギーだけではなく、その地特有の社会状況も考えていかなければならないのではないだろうか。

今回の記事ではスリランカにおけるカースト問題についてお話しした。記事の分量上、詳しくは論じることができなかったがその問題の端緒が伝わったならば幸いである。

主な参考図書はこちら↓

スリランカ政治とカースト: N. Q. ダヤスとその時代 1956〜1965

次の記事はこちら

前の記事はこちら

【インド・スリランカ仏跡紀行】の目次・おすすめ記事一覧ページはこちら↓

※以下、この旅行記で参考にしたインド・スリランカの参考書をまとめた記事になります。ぜひご参照ください。

〇「インドの歴史・宗教・文化について知るのにおすすめの参考書一覧」

〇「インド仏教をもっと知りたい方へのおすすめ本一覧」

〇「仏教国スリランカを知るためのおすすめ本一覧」

関連記事

コメント