Table of Contents

(30) A brief explanation of what kind of Buddhism is Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka - a few words on the differences with Japanese Buddhism

Previous Article(29) Why wasn't I moved by Sri Lanka's holy sites and Buddhist monuments--thinking about religion and the "context of life?"In the following section, I spoke about the context of "Buddhism of the Sinhalese (Sri Lankan Buddhists), by the Sinhalese, for the Sinhalese.

Sri Lankans have their own context, just as Japanese have their own context. The differences in context will surely affect the differences in religion and culture.

In this article, I would like to take a break from my travelogue and talk about the nature of Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

The reference for this article is published by Kaze Kyosha.An Invitation to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia.The book is called.

This book is an excellent introductory book and a recommended reference for beginning students to get a clear idea of what Sri Lankan Buddhism is all about.

So let's get started.

Characteristics of Theravada Buddhism

In order to grasp the characteristics of Theravada Buddhist society, it is easy to first distinguish between "ordained" and "lay" Buddhism.

An "ordained person" is a practitioner who leaves home to lead a group life in a temple, in other words, a monk. In contrast, ordinary people who are not ordained are called "zenke-sha" (also called lay people).

As discussed below, ordained persons are forbidden to marry or drink alcohol, and live in a world apart from the secular world (the general society in which ordained persons live). So, it is not the case that zenke people lead a life unrelated to religion. The zenjutsu practiced Buddhism in a different way than the ordained. This dual structure is sometimes explained as "the two kinds of Buddhism" [Ishii 1991].

Kaze Kyosha, Rihiro Wada, Takahiro Kojima, Kanako Otsubo, Yoshiyuki Masuhara, Takashi Shimojo, and Yoshio Sugimoto, Invitation to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, P13

In Sri Lanka and other Southeast Asian Theravada Buddhist traditions, the distinction between ordained and ordained practitioners is strictly enforced.

This is the first major difference between Sri Lankan and Japanese Buddhism. Originally there was this kind of ordained principle in Japan as well, but after the Meiji Restoration, wifehood became common in Japanese Buddhism, and Buddhism changed to a form that blended in with society. (The Jodo Shinshu sect, to which I belong, is a unique sect in that it allows wife-owning in the first place.)

I will speak later in this travelogue of the changes in the appearance of Buddhism in Japan.

First of all, at any rate, the strict distinction between "ordained" and "ordained" is very important to understand Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Buddhist Beliefs of the Zenkeisha

This section is a bit long, but it is a very clear explanation of how Theravada Buddhism works, and I would like to introduce it to you.

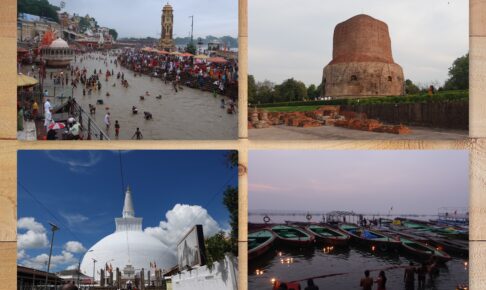

Early in the morning, a few depressed ordained people walk in a line through the village or town. They walk in a line, holding bowls in their hands and barefoot. When they notice a zakeisha standing in front of the doorway of a house, they stop and accept a donation of cooked rice or side dishes from the zakeisha. Many leave without exchanging a word with the zeiken. This is a scene that is repeated every morning in all Theravada Buddhist communities.

Ordained Theravada Buddhists are not supposed to engage in agriculture or commerce. In other words, they do not work for a living. Therefore, they depend on donations from those who are ordained to provide their daily meals. Although ordained Buddhists live apart from the secular world, they cannot even sustain their lives without the support of those who are ordained.

This begging bowl may be a little confusing for us. When the ordained person finishes placing the cooked rice in the bowl, the zenkeisha person squats down and gratefully puts his hands together. On the other hand, the ordained person who received the donation kept his eyes fixed on the bowl on his arm and did not bow, clasp his hands together, or say thank you to the zenkeisha who had prepared the meal in the dark of the morning. The zenkeisha were indeed too good-natured. What is the benefit of having pious zenke people serve ordained people?

In fact, the layman also gains. In fact, zenke people do not "gain" but "accumulate virtues" (also called "merit"). The act of accumulating virtues is called "accumulating virtues" or "accumulating virtues" or "accumulating virtuous deeds" (Sekitoku is read as "Sekitoku" or "Shakutoku"). The same idea exists in Japan, but in Theravada Buddhist societies, the enthusiasm of the people for accumulating virtues is far greater than in modern Japan. This enthusiasm is one key to explaining why Theravada Buddhism is so vibrant.

The virtues sought by those who are ordained are first and foremost those that support the practice of those who are ordained. As will be explained later, the virtues to be accumulated include leading a righteous life and helping others who are in need.

Why, then, do the people strive to accumulate virtues? This is because they believe that accumulating many virtues will guarantee happiness in this life and the next. The content of happiness can be basically anything, for example, to be rich, to have a good marriage and children, not to get involved in human troubles, to gain status and power, to be healthy in body and mind, to be beautiful men and women, to be musicians and athletes, and so on. In other words, it is fine to be faithful to one's human desires. In the case of ordained believers, they practice Buddhism with the aim of eliminating such desires, while ordained believers are, in a sense, able to do the right thing as Buddhists even if their desires are fully exposed. Since one only needs to accumulate merits and virtues in order to achieve happiness, it is not surprising that some people devote enormous amounts of energy to accumulating virtues on a daily basis, and that Buddhism is thriving as a result.

Kaze Kyosha, Rihiro Wada, Takahiro Kojima, Kanako Otsubo, Yoshiyuki Masuhara, Takashi Shimojo, and Yoshio Sugimoto, Invitation to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, P14-15

What do you think? Some of you may be surprised to read this commentary.

In Theravada Buddhism, a zazen practitioner accumulates merits in order to "become rich, have a good marriage and children, not to be involved in human troubles, to gain position and power, to be healthy in body and mind, to be beautiful, to be a musician or an athlete," and so on.

Needless to say, the sense of "living a better life" is important, as Buddhism teaches. However, as a double-edged circle, this kind of wish for worldly benefits is also recognized. This is quite different from the strict image of Buddhism in Southeast Asia.

This belief in the benefits of Buddhism is also strongly reflected in the Buddhist collections of stories that are still popularly read in Southeast Asia.

Overall, after reading this collection of stories, I still felt that there is a very strong atmosphere of accumulating good deeds, especially chanting the name of Buddha, making offerings to the Order, and doing good things for others, which will rebound greatly to one's own benefit in the next life and in this life. For more details, please refer to the article above if you are interested.

Now let's continue to look at the commentary. What is said here is also very important.

However, one might think that if one wishes for happiness, it is enough to put one's hands together with the gods and Buddha, as in Japan. The hearts of those who seek happiness should not necessarily turn to support for ordained people. Why, then, for Theravada Buddhists, does this pursuit of happiness lead them to, for example, get up early in the morning and offer meals to ordained people?

This is because the two ideas of karma and reincarnation support the practice of accumulative virtues. These are familiar in Japan, but they have a greater influence on people's behavior in Theravada Buddhist communities.

Karmic retribution is the idea that if you do good deeds (good deeds), you will be happy, but on the other hand, if you do bad deeds (bad deeds), the retribution will come back to you. It is the same as karmic retribution or self-reward. Among Theravada Buddhists, this has taken root as a guideline for people's conduct. Therefore, when we want to be happier or escape from immediate suffering, it is not enough to pray to the gods and Buddha. Destiny is not left in the hands of God or Buddha. It is the karmic reward philosophy that sees that everything depends on one's own actions. Since only I can save myself, it is also called the philosophy of self-help.

Reincarnation is an ancient Indian belief that one is reborn again after death. Buddhists believe that those who have done good deeds in their lives will be reborn in the heavenly realm (the world of the gods) after death. Or, if heaven is not possible, they are reborn as human beings, the next level. However, if they lead a greedy life, they will be born as a hungry demon in their next life. A hungry ghost is a pitiful being who cannot satisfy his greed.

Those who have repeated bad deeds will be born as animals or worms in the next life. Those who are even more wicked will go to hell, where they will have to spend a long time suffering more than hungry ghosts and animals.

To accumulate merits is, so to speak, a paraphrase of doing good deeds, an act of daily devotion in the hope that one's life will be blessed with better fortune, that one will be reborn in the heavenly realm after death, that one will be born in a wealthy and comfortable situation if one is human, and that one will not be born into hungry ghosts, animals, or hell. I hope that I will not be born into a hungry ghost, a beast, or a hell.

Some line breaks have been made to make it easier to read on smartphones, etc.

Kaze Kyosha, Rihiro Wada, Takahiro Kojima, Kanako Otsubo, Yoshiyuki Masuhara, Takashi Shimojo, and Yoshio Sugimoto, Invitation to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, P15-16

Now, the fundamental issue has been discussed here! The basis of Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka and other Southeast Asian countries is this karma and reincarnation.

In Sri Lanka, there is a belief in the afterlife. This in itself is not unique in the world. It is something that can be considered anywhere in the world. Even the Japanese believe (or have believed) in the next life. (Or they have believed in it).

But what is decisive here is that the Sri Lankan view of the next life of reincarnation is an Indian one, in which human beings are reborn as a complete reincarnation in the next life. In other words, it is a cyclical view of life and the next life. What is special about this view is that in the next life, we will reincarnate in this world and live another life. For example, if one's mother dies, one's mother may be reincarnated somewhere in this world. She may be living as an animal or an insect.

In contrast, the Japanese Buddhist view of the next life is different from such a cyclical one. When we unconsciously think of the next life, we may imagine that we will go directly to the next life and live there. When we say, "May the deceased rest in peace," we are thinking that the deceased is living "as is" in some other world.

In other words, for us, this world and the next world are continuous: Mr. A will live as Mr. A in the next life. I believe that this is exactly the influence of the Chinese cultural sphere, which has long held the ideas of immortality and the spirit of the soul.

The cyclical Indian view of life and death and the continuous Chinese view of life and death. This difference may have a strong influence on the Buddhism that takes root in the region. And it also has a great influence on the style of each Buddhism. It is not a question of which is better and which is wrong.

And there is one more part I would like to introduce.

Suppose, for example, that you are a Theravada Buddhist and have led a debauched life, thinking that you can accumulate virtues in your old age. However, you accidentally died early. What should you do? In such a case, there is a way of thinking that you can escape from hell as quickly as possible by having your remaining family members send you merit and virtue.

The transfer of merit to the "prayers for the repose of the soulIt is called "the You may have heard of it in Japan at funerals and other occasions.

One of the most common rituals that we often see is that after the parishioners have contributed food and goods to the priests, they drip water from a small bottle or glass into another container while listening to the chanting of the priests (in some areas, the parishioners chant the sutra together). In this way, the merit and virtue accumulated in the past can be shared with relatives and other deceased people. The "sharing" does not mean that the merits of the person who has accumulated virtues will be reduced (some people believe that it will be increased).

Some people believe that merit is transferred to all living beings, including animals and hungry ghosts, in addition to the deceased. It is worthwhile to compare the interpretations of gyokai, as they vary considerably from region to region and scholar to scholar.

Some line breaks have been made to make it easier to read on smartphones, etc.

Kaze Kyosha, Rihiro Wada, Takahiro Kojima, Kanako Otsubo, Yoshiyuki Masuhara, Takashi Shimojo, and Yoshio Sugimoto, Invitation to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, P19-20

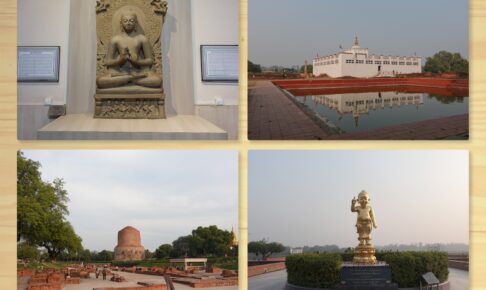

This share of merit is exactly what I saw in Anuradhapura.

Led by a band of musicians, the group came to the Sree Maha Bodhi tree to make merit. They are holding offerings in their hands. Offering offerings to the holy Sree Maha Bodhi tree is a very significant merit. Many people came to this procession to share their merits. This is the very principle of the "gyokai".

In Summary.

An Invitation to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia."In the following section, the faith of the ordained believers and the style of the ordained believers are also discussed, but it is impossible to introduce all of them here due to the volume of the book.

But in closing, I would like to quote one more commentary as a summary. Let's read it carefully, because it is an excellent and compact commentary on what Theravada Buddhism is all about.

To summarize the point, the Theravada Buddhist society is founded on the karmic reward philosophy that one's fate depends on one's deeds.

However, it is difficult for people to change their behavior even if they know it in their heads. Therefore, the incentive to put thought into action was "merit. Rather than a vague expectation that doing good deeds will bring good results someday, it is more enjoyable to think, "Now that I have done good deeds, I have accumulated merits and virtues.

Supporting Buddhist monks, living a righteous life by observing the Five Precepts and the Eight Precepts, and helping others who are in need, etc., without expecting anything in return, can convince people that "Oh, thank God, I have accumulated merit and virtues. In the case of a layperson, it does not matter if the purpose of accumulating merits is to be covered with desires.

On the other hand, ordained believers, on the other hand, are committed to the ultimate goal of nirvana by renouncing greed, observing precepts, studying Buddhist scriptures, meditating, and engaging in other practices that interest them (see the next chapter for more information on ordained life). This striving for oneself is the basis of Theravada Buddhism, which is called self-interest.

However, as we have seen in this chapter, there are many activities that start from self-interest but result in altruism. Those who are ordained support those who are ordained for the purpose of accumulating virtues for themselves, help others, andprayers for the repose of the soulTransferring merit as a ordained persons preach, chant sutras, and offer counsel for the benefit of those who are ordained. Thus Theravada Buddhism is also associated with altruistic acts and activities.

Some line breaks have been made to make it easier to read on smartphones, etc.

Kaze Kyosha, Rihiro Wada, Takahiro Kojima, Kanako Otsubo, Yoshiyuki Masuhara, Takashi Shimojo, and Yoshio Sugimoto, Invitation to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, P37-38

This is the basis of Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka and other Southeast Asian countries. This article is not a travelogue, but a discussion of the doctrinal aspects of Theravada Buddhism, but such basic knowledge is necessary for those who wish to visit Buddhist sites in Sri Lanka and mainland India.

It is not necessary to suddenly understand everything that has been said here. I intend to share some of what I have said with you, along with the actual situation on the ground. I hope you will feel free to follow along.

I referred to it this time.An Invitation to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia."is an excellent introduction to Southeast Asian Buddhism. I highly recommend it.

Let's resume our travelogue in the next article. Our next destination is Jaffna, the northernmost city in Sri Lanka.

This is a place that is critically important for understanding the history of Sri Lanka. The question "What is Sri Lanka for me?

*Below is an article with reference books on India and Sri Lanka that we have referenced in this travelogue. Please refer to them.

periodA list of recommended reference books to help you learn about Indian history, religion, and culture."

periodA list of recommended books for "those who want to know more about Indian Buddhism."

periodA list of recommended books to help you get to know the Buddhist country of Sri Lanka."

Next Article.

Click here to read the previous article.

Related Articles