The "banality of evil" theory is overturned! Summary and Comments on "Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Peaceful Life of a Mass Murderer"

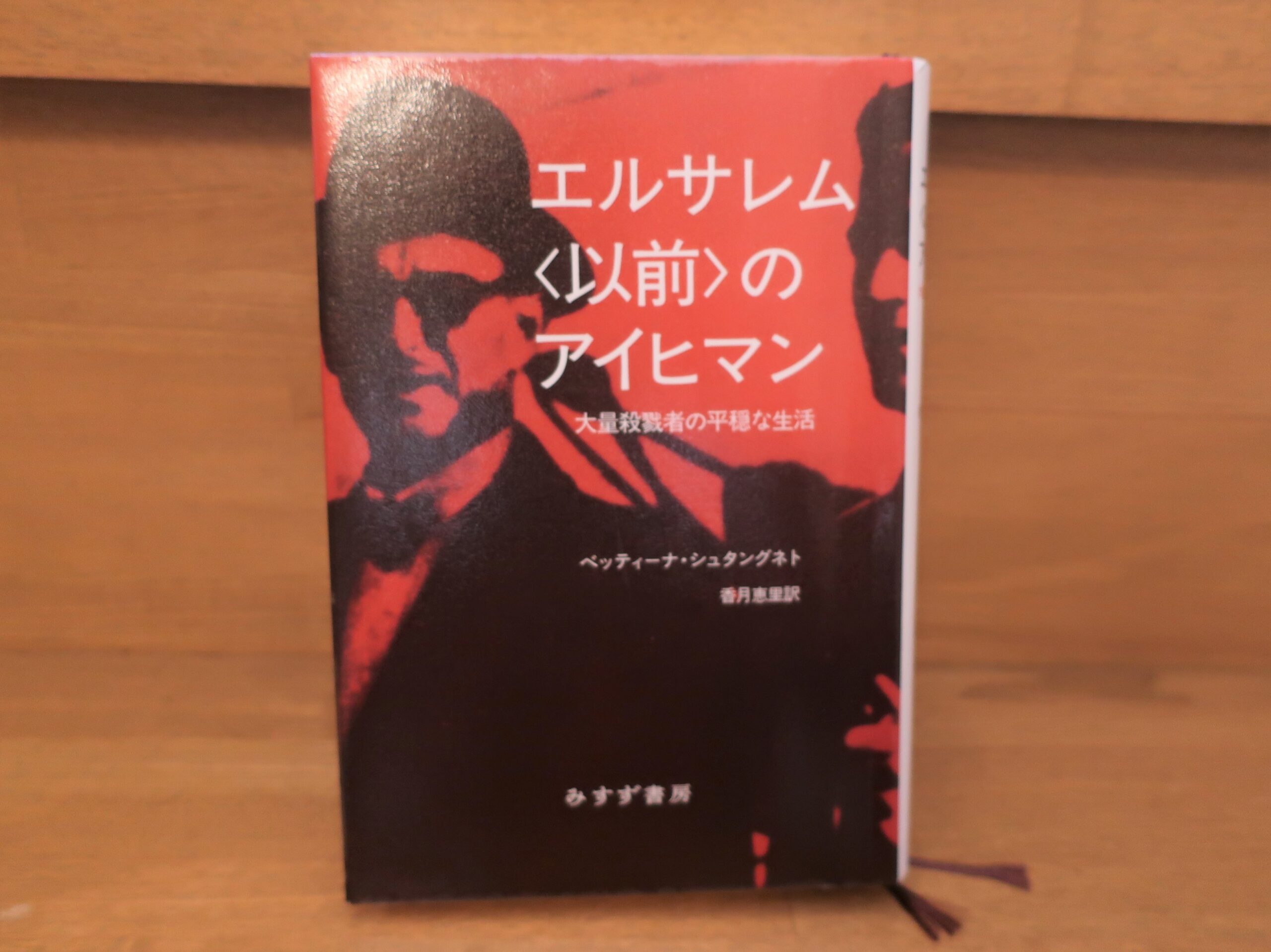

The book introduced here is "Eichmann in Jerusalem [before Jerusalem]" written by Bettina Stangnet and translated by Eri Kozuki, published by Misuzu Shobo in 2021.

Let's take a quick look at the book.

Adolf Eichmann, the man responsible for transporting Jews to concentration camps, was a key player in the extermination program. Although there is a sense that this SS lieutenant colonel has been discussed to death, most of the important historical documents have actually been neglected. The majority of the key historical documents have been left out: Eichmann's own writings and audio recordings.

In Argentina, where Eichmann fled after the war, a former Nazi community had been established. There, Eichmann participated in a roundtable discussion hosted by W. Sassen, a former member of the armed SS. Sassen recorded it and created a transcript of the audio, which amounts to more than 70 tape volumes.

Eichmann in Argentina wrote a large number of his own, and after he became a prisoner in Jerusalem, he wrote 8,000 pages of self-justification.

It is surprising that these documents have not been comprehensively studied, but they are scattered throughout the country, the volume is enormous and the content intolerable, and the task of establishing their value as historical documents has fallen heavily on later researchers because of their open recordings in Argentina, which he himself testified were false. This book is the sobering achievement of a philosopher, and a dialogue with the pioneering Hannah Arendt.

If we wish to know how Eichmann's self-staging in Jerusalem relates to this criminal and to his success as a murderer, it is inevitably necessary to go back to Eichmann before Jerusalem and to go behind the interpretations based on images of Eichmann made in later times" (Introduction (from)

Misuzu Shobo, Bettina Stangnet, translated by Eri Kozuki, "Eichmann in Jerusalem [before]" Back cover

First of all, let me say this.

This book is shocking.

Previous Article"The Banality of Evil: Arendt, "Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil."But as we will see, Arendt proposes the theory of the banality of evil through the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem.

Eichmann, the man responsible for carrying out the "Final Solution," must have had a strong hatred for the Jews. He must have been a vicious and brutal man. That is what those who paid attention to the Eichmann trial imagined (or hoped). Arendt, however, wrote that he was not at all like that.

Such an attitude is expressed in the subtitle of this book, "A Report on the Banality of Evil. The English word "banal," translated as banal, is an adjective meaning "somewhat familiar," "commonplace," or "ordinary. It means that he was a very ordinary person who could be found anywhere.

From a young age, he was an ordinary man who "did not seem to have much of a future" and who "preferred to join some organization" rather than forge his own path. He was "terribly eager to advance himself" within the organization, Arendt wrote.

NHK Publishing, Masaki Nakamasa, Evil and Totalitarianism: Thinking from Hannah Arendt, p 165-166

Eichmann was not a man of evil incarnate, but an ordinary human being who could be found anywhere. He was merely one of the cogs in the bureaucratic system, a clichéd human being who blindly followed orders. Such men were committing genocide." This is Arendt's argument.

Arendt's argument sparked a worldwide furor and made her a household name. The phrase "the banality of evil" also became established throughout the world.

However. In "Eichmann Before Jerusalem," Arendt's theory is overturned by a shocking revelation.

This is because the book uses recently researched documents to tell the story of Eichmann's words and actions during his Nazi years before his arrest by the Mossad, and during his fugitive period in Germany and Argentina. In other words, it literally tells the story of Eichmann's life before the "Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem.

And the Eichmann revealed there was the opposite of "evil cliché". The book tells us that Arendt fell into Eichmann's carefully planned trap in Jerusalem. Eichmann was no mere cog in the wheel of power.

The book also describes the "I was never a Jew hater, and I never once wished to kill a human being.The testimonies of "the most important person in the world" and others will be revealed to have been a big lie.

Arendt did not know Eichmann before his arrest. And the trial continued without most of the world knowing what he was really like.

This does not destroy all of Arendt's theory of the banality of evil, but it does make it quite tough to apply it to Eichmann, which is what the book is trying to say. This is quite shocking.

This book is over 600 pages long if you include the notes. What kind of a person was Eichmann before the period of the cover-up in Jerusalem? And what kind of person was he seen as by those around him? We will look at that in considerable detail.

As mentioned in the introduction to the book above, I was surprised to learn that such a fact had been overlooked until now. The book also tells the story of how it happened in detail. This was also very interesting. Here you can learn about the difficulty of the unprecedented case of the Holocaust and the delicate issues of postwar international politics. The book itself was published in 2011, so it has already been 10 years since this fact came out. I also felt that this Eichmann fact, which could shake up the notion of the "banality of evil," could have been reported more extensively, but I don't know the circumstances of that.

There are so many passages in this book that I would like to introduce, but I will only mention one passage that struck me as particularly memorable. The following is from shortly after Eichmann's capture by the Israeli intelligence organization Mossad in Argentina.

When Eichmann found himself unexpectedly ensnared by an irreconcilable enemy, he quickly realized which of the images of himself circulating in the public mind would best serve his defense. The image of the cautious bureaucrat - but minus the detrimental part, which he added in Argentina. To this pose, he hoped to add two elements that would protect him from the executioner's block. He wanted to be protected from the executioner's table by adding two elements to this pose: he was innocent, and he knew what others did not know about the murder of the Jews. Besides, he even had the luxury of adding his own insight. I knew, and yet I could do nothing about it" ("My Escape," p. 39).

A renowned expert on the "Jewish question," an interagency coordinator of the extermination project, a man who celebrated the progress of the genocide with his boss by the fireplace sipping cognac, claimed that he was nothing more than a helpless minute taker with no authority, sitting at a small table in the corner "sharpening his pencil" at the Vansee Conference. He claimed that he was just sitting at a small table in the corner, "sharpening his pencil" at the Vansee meeting. The man who in Argentina had explained in detail and proudly how his name had already become a single symbol before the war, and who had deflected the contents of a collection of newspaper articles about him, now claimed that "until 1946, my importance was almost zero. The impending trial, he says, is a misunderstanding caused by "fifteen years of being accused, slandered, and persecuted by the whole world. I am also a victim," he says in his final statement to the court.

For the sake of this masquerade, Eichmann is even willing to define himself in ways that would have driven him insane in the past. He said that he was a "narrow-minded," "bureaucratic," "kouryoku" man who "never exceeded his job description. He might have had a little fun with this last lie. (Eichmann always boasted of his scheming skills. And the interrogators had carefully observed that this prisoner was particularly animated when he used his tricks.

Such a label he applied to himself was the image of an enemy of National Socialism, and "bureaucracy" was the exact opposite of the self-definition of an SS member. Bureaucracy could be used like a weapon, especially against those who believed in the value of bureaucracy. Already when he was in power, Eichmann understood the art of outwitting other agencies and victims with corrupt bureaucratic harassment, and he knew how to use this subtle tool that came with power. But in Israeli cells, being a bureaucrat sounded much more innocuous than being an SS member. A cautious bureaucrat, free of fanatical National Socialism, an ordinary man who loved learning, the Enlightenment, and internationalism, and who loved nature. A man who, fifteen years ago, had finally been able to break free from the burdensome orders and criminal government and return to his true self - this was the image of Eichmann that the Israeli defendant had chosen to portray at the end of his life. Thanks to his ability to assume the role and perform it perfectly, Eichmann continued to strike these poses and refine them. In addition to the gleeful interrogator, the diligent historian, and the international law-abiding pacifist, Eichmann was joined, with the help of Kant and Spinoza, by the ultimate moral and - this time without the "voice of blood" - existential philosopher.

Misuzu Shobo, Bettina Stangnet, translated by Eri Kozuki, Eichmann in Jerusalem [before], p. 500-502.

This passage alone gives you a sense of how Eichmann was scheming to get away with his crime, doesn't it?

Hannah Arendt was indeed deceived by this mask of Eichmann. Arendt's "banality of evil" may be applicable to low-level officials, but what about Eichmann? Rather, Eichmann says, "Everyone can commit evil, even if unintentionally. I am only a cog. I had no choice. It was not a crime I wanted to commit. As a result, he was executed, but the theory of "banality of evil" was used as a cover for his crime.

I spoke in my previous article about whether the banality of evil can be exonerated.

He tries to pretend that his sins did not exist by using the banality of evil as a cover. Or he judges himself that he must be forgiven.

In doing so, we have discussed in this article the reality that the perpetrator will try to return to his/her former routine with impunity.

I strongly felt that Eichmann, too, used the banality of evil as a cover to cover up his own deeds.

Arendt could only know Eichmann at the time of the trial in Jerusalem. Therefore, he was only able to construct his theory based on what little information he had.

The author makes a very interesting point about this.

It is our desire to obtain his image without strictly observing him that supports the power of SS leader Eichmann. This man skillfully exploited the human desire to see what he wanted. Eichmann of Jerusalem convinced those who wished to understand him that there was a bridge leading to his worldview. This is why we must look hard and critically at the swamp of perverted ideas found in the "Argentine Documents. Otherwise, we will fall into Eichmann's trap of playing with the evil gods.

Misuzu Shobo, Bettina Stangnet, translated by Eri Kozuki, Eichmann in Jerusalem [before], p 503-504.

Arendt was a prominent philosopher who had studied under Heidegger and Jaspers since that time. She flew to Jerusalem in the fullness of time to investigate the Eichmann trial.

Hannah Arendt took the way she learned to understand. She read repeatedly what pertained to the man who wrote and spoke there. She did so on the assumption that only those who wish to be understood write and speak. Arendt read the transcripts of interrogations and trials more thoroughly than almost anyone else had done. But it was precisely by doing so that Arendt fell into a trap. For Eichmann in Jerusalem was no more than a mask. She did not recognize it.

Misuzu Shobo, Bettina Stangnet, translated by Eri Kozuki, Eichmann in Jerusalem [before], p. 13.

As a philosopher, Arendt believed that 'people speak or write something down because they want "someone to understand them. That is why he dutifully read Eichmann's trial transcripts, from which Arendt developed his own theory, the concept of the banality of evil.

But, as the author states, that was Eichmann's trap. Eichmann exploited the desire of people like Arendt to understand him. Arendt, as a philosopher, had a desire to construct a theory of man through the diabolical Eichmann and to elucidate the incomprehensible phenomenon of the Holocaust. That in itself is not to blame, but it was precisely this that turned out to be the pitfall.

Theories neatly resolve huge, incomprehensible, and complex events. Nothing is more appealing to thinkers and philosophers. But whether such attempts really lead to a resolution or understanding of the situation is a question that remains unanswered.

This was also advocated by Soviet writer Vasily Grossman, who, along with Arendt, was a strong critic of totalitarianism.

Totalitarian scholar Timothy Snyder, in his book Bloodland Hitler and Stalin's Massacre, describes Arendt and Grossman as follows

From Arendt and Grossman, we can derive two clear ideas.

For one thing, a legitimate comparison of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union requires not only an account of the crimes, but also an examination of the humanity of all those involved - victims, perpetrators, bystanders, and leaders.

The other is that we should start with life, not death. Death is not a solution, but only a theme. Death should bring anxiety, not satisfaction. Above all, it should not serve as a rhetorical device to bring the story to a neat and tidy conclusion. Life gives meaning to death, not death to life. So the important question is not what political, intellectual, literary, or psychological resolution to the fact of mass murder should be. The settlement is a false harmony. It sounds like a beautiful song sung by a dying swan, but it is in fact the song of the sirens, the nymphs of the sea, who lure the sailors and drag them to the bottom of the water.

*Lines have been changed as appropriate.Chikuma Shobo, written by Timothy Snyder, translated by Yukiko FuseBloodland: The Truth About Hitler and Stalin and the Holocaust.Bottom P245

Don't let the rhetoric serve to bring the story to a neat conclusion."

Settlement is a false harmony."

By abstracting and theorizing an event, the event is indeed easier to understand.

But is that really the end of the story? Can the life of each person's suffering be buried in a giant theory? Grossman also expresses these thoughts in his novel.

It is his masterpieceLife and Destiny.", ,All things flow.I also felt strongly when I read the

It is true that the temptation to settle neatly with theory is hard for us to resist.

But if that is the end of the story, we may lose sight of what is important.

Eichmann Before Jerusalem is exactly, as Timothy Snyder says, "the kind of book that is a real treatise."It also examines the humanity of all those involved - victims, perpetrators, bystanders, and leaders." This is a book that will

Arendt's phrase "the banality of evil" is all too well known.

I agree with the concept that "anyone can do evil," and I think the significance of communicating this to the world was tremendous.

But the paradox is that Eichmann himself, the man who inspired the theory, was the very opposite of "evil cliché"...

The theory that emerged from Eichmann is not applicable to Eichmann.

But for humanity as a whole, "evil banality" is a theory that can happen to anyone, anywhere, at any time.

We are confronted with such contradictory issues.

The question of whether the "banality of evil" can be exonerated is not one that I can answer right now. But through the Srebrenica and Rwanda genocide, this question has become a very big one for me.

We will continue to consider this as an issue for the future.

The above is "The "banality of evil" theory is overturned! Eichmann Before Jerusalem: The Peaceful Life of a Mass Murderer".

Next Article.

Click here to read the previous article.

Related Articles