E. Saratchandra's "The Deceased" Synopsis and Impressions - Comparable to that "Oshin"! A novel diptych set in Japan that became immensely popular in Sri Lanka!

The book introduced here is "The Deceased," written by Edirivila Saratchandra and translated by Tadashi Noguchi, and published by Nan'undo in 1993.

Let's take a quick look at the book.

The author, who first came into contact with Japanese society and culture as a Sinhalese national visiting Japan, a country then completely unknown to him, describes his amazement at the traditions that live on in Japan and the Japanese way of looking at things.

AmazonProducts Page.

I picked up this piece from Mamoru Shono, whom I have previously mentioned on this blog.Adventures in Sri Lankan Studies."It was introduced in the following way in

Through the medium of television, "Oshin" became the most famous Japanese female name in Sri Lanka. However, until "Oshin" appeared in Sri Lanka, "Noriko" was the most popular name. On the streets of Colombo, there are several women's clothing stores with signs saying "NORIKO". This is because a famous Sri Lankan contemporary novel describes a Japanese woman named "Noriko".

The author Edirivila Saratchandra's two novels set in Japan, "Malagi at (The Deceased)" (1959) and "Malange auruda (The Day of the Dead)" (1965), are two of the most read Sinhala novels to date. These two novels are probably the most widely read Sinhalese novels to date. The Japanese edition of "The Deceased" and "Omeibi" has been published in two parts, one part and the other part, in a single novel volume. The translator is Tadashi Noguchi, whose life's work is the study of Sinhalese literature. Mr. Noguchi majored in Sinhalese literature at the University of Peradeniya.

The encounter and parting of a Sri Lankan painter returning from London and a Japanese woman. The story takes place in Okusawa, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo in the 1950s, when Sri Lanka was economically richer than Japan. In those days, Sri Lankans and Japanese may have met on a more equal footing than now.

Noriko, who works at Midori Izakaya, meets the painter Dewendra, with whom she slowly falls in love. The main character, a Sri Lankan living in Japan, seems to be the alter ego of the artist, who was invited and spent a year in Japan. Noriko and the Sri Lankan painter talk about traditional Japanese arts such as kabuki, tea ceremony, and Japanese cuisine. The artist, attracted by ukiyoe, came to Japan to study woodblock prints.

When I arrived in Japan, the first thing I noticed was the abundance of color everywhere I turned, and I had never seen such a country before. Even the knick-knacks we use every day, such as matchboxes and teacups, are beautifully shaped and painted with beautiful colors, and this way of life, surrounded by such beauty, is what I saw as the ultimate aesthetic sense that the Japanese respect."

Sinhalese readers learned about Japan through this novel. The text's expression, filled with a sense of color, captivated readers and became a bestseller. (omitted).

Parts of this novel were published in textbooks from the 1960s to the 1970s, and had a major impact on the perception of Japan among young Sri Lankans at the time.

Do you know Noriko?"

And the fact that Sri Lankans would suddenly ask, "How did you get here?" is a testament to the novel's influence.

Minamifune Hokumasha and Mamoru Shono, Adventures in Sri Lankan Studies, p. 171-174.

I was surprised that there was a Sri Lankan novel that had more influence than that "Oshin" novel.

The author, Saratchandra, actually visited Japan in 1955, and it is evident that the intense experience he had there has strongly influenced this book.

In particular, in the first part, "The Deceased," the narrative is primarily directed at Dewendra, a Sri Lankan painter. The story vividly depicts what Japan was like at that time as seen from his gentile perspective. As the above commentary has already given a glimpse of, Sri Lankans at that time imagined the country of Japan from reading this novel.

I picked up this book thinking that this work must be valuable in understanding how Sri Lankans viewed Japan at that time.

And there is another major reason I read this book.

That is the presence of Martin Wickramasinghe, another leading Sri Lankan writer, whom we have mentioned in previous articles.

Martin Wickramasinghe is also not well known in Japan, but he is known as a world-class writer representing Sri Lanka. I myself became aware of his existence while studying Sri Lanka.

Wickrama Sinha'sThe Changing Village., ,The Age of Transformation.", ,The End of Time.I have already introduced the trilogy of "The Lost" in this blog. I have become a fan of Wickramasinghe's work because of the excellence of this trilogy, but it was Edirivila Saratchandra, the author of "The Deceased," with whom Wickramasinghe had a heated literary debate.

The controversy between these two leading figures in Sri Lanka is very important in understanding the flow of Sri Lankan literature. Let us now take a look at how it all went down. The following is an easy-to-understand explanation of the controversy at the end of "The Deceased.

S. W. R. D. Bandaranayaka, the leader of the Liberal Party, which had come to power from the Nationalist Party that had been in power until 1981, passed a bill (1956) in Parliament to make Sinhala the only official language, one of his election promises. This coincided with A. Dharmapala's Buddhist revival movement, and the momentum of nationalism was heightened. Naturally, accusations and attacks from the minority Tamil nationalists in the country swirled, and the situation escalated into the great ethnic riots of 1958.

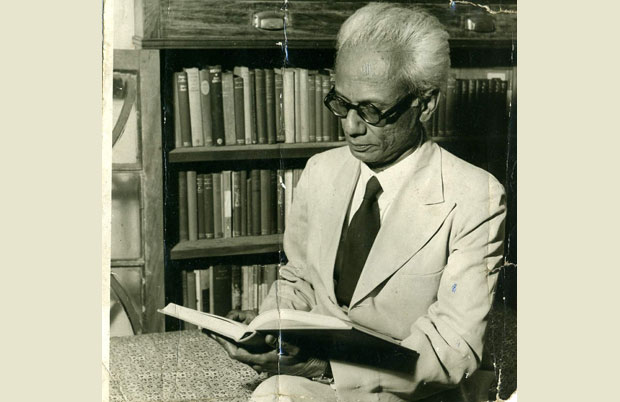

Unlike the impulsive anti-Westerners such as P. Sirisena mentioned earlier, the Sinhalese intelligentsia, which began to search for a new literary trend and a restorationism refined by reason, began to be active in the 1940s. Martin Wickramasinghe (1891-1976) was born in Koggala, in the southern part of the island. At the age of 10, his father died of illness, and he was educated in the village school for less than five years, but during his childhood he learned Sinhala, Pali, and Sanskrit from the village priest, and was noted as a "boy of unusual talent. At the age of 14, with a mother and seven sisters, life was difficult and he left for Colombo in search of work. When he was nineteen, his mother passed away, and he was left with the heavy responsibility of being the head of the family. After publishing his first novel "Leela" (the name of the female protagonist, 1914) at the age of 23, he worked as a journalist for newspapers such as Dinamina and Silmina, and married in 1925. He married in 1925 and had his first son the following year, but died of illness within three months. After becoming the father of three sons and three daughters, he began to write in earnest and embarked on the path to becoming a professional writer.

He did not reject all Western culture and thought, but believed that the pursuit of reason alone was not enough to understand the essence of things. As democratization was being promoted, he did not see the decline of traditional culture as a step toward disintegration, but rather as a process of change, and he took a sober view of the process, rejecting mere nostalgia. In 1969, with the publication of "The Changing Village," he combined the techniques he had absorbed from Western literature with the traditional flow of Sinhalese literature, giving birth to a unique contemporary Sinhalese literary work and establishing himself as a writer. The End of Time" (1949) and "The End of the World" (1957), which correspond to a trilogy, are written in two or three parts, and depict the rise and fall of three generations of a family in a sophisticated and elegant style, against the background of the trends and ideas of the times, including the conservative village people and the rise of the working class and the emergence of a radical upper middle class.

Abnegation" (1956) is considered to be one of his outstanding works among his more than 80 lifetime works (including critical works written in English). Through the love story of Alawinda, a man born in a village and raised in the village community, the author depicts a man in distress, caught between the world filled with traditional customs and the ideal world he envisions, who eventually falls into lethargy, disappointment, and frustration.

From the early 20th century to the mid-19th century, modern literary works tended to be modeled on Western novels by all authors. M. Wickramasinghe was no exception, using Anton Chekhov's techniques, and his long novels were so inspired that the influence of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky can be clearly seen. The Liar" (1924) is reminiscent of "The Adventures of Baron Raspe" by the German writer Raspe, and "The Necklace of Diamonds" (1927) is even said to be an adaptation of "The Necklace" by the French writer Guy de Maupassant.

Reading these works, one can see that Sri Lanka's literary soil had something in common with the advance of the Russian and French classes into the country, as well as with the upsurge of revolutionary spirit in Russia, and that the groundwork for a strong sympathy among Sinhalese readers may have sprouted. The importation of Russian literature was permitted in 1956, and this trend was further accelerated.

Nan'un-do, Edirivila Saratchandra, translated by Tadashi Noguchi, The Deceased, p372-374

So much for the commentary on Martin Wickramasinghe, but again, what cannot be overlooked here is the connection with Russian literature. I too have read his trilogy and clearly feel the influence of Chekhov and Dostoevsky. In the second novel, "The Age of Change" ("The End of the World" in the quote above), I also felt the naked realism of a French literary giant like Emile Zola.

I have been studying Sri Lanka and have always felt something in common with Japan, not only in literature. The relationship between India and Sri Lanka is similar to that between China and Japan. Perhaps because of this similarity, I also feel some similarities in history and religion. And in terms of literature, the fact that Russian literature is particularly favored in Sri Lanka makes me think that there must be some commonality in the national character and thought of the people.

Let's continue to look at the commentary. This is where Saratchandra finally comes in.

This trend was turned on its head by E. R. Saratchandra (1914-), an elite writer who studied traditional Indian arts and later earned a doctorate in Western philosophy from the University of London. He wrote a literary review entitled "The Modern Sinhala Novel" (first published in 1943), which caused much unprecedented controversy and played an important role in bringing about a turning point in Sri Lanka's literary history. In other words, it awakened the readership to the level of criticism, stimulated the demand for more advanced literary works, and improved the quality of the works.

Since his first visit to Japan in 1980, he has been deeply moved by the traditional culture of Japan and has written two novels, "The Deceased" (1959) and "The Day of Death" (1965), both set in Japan, in which he has developed a brilliant prose style that combines a wide variety of elements including stylistic development, metaphorical usage, and flexibility in Sinhalese language. Many readers were intoxicated by the freshness of Oriental Japan and its culture, which had been completely unknown until then, and "The Deceased" became the biggest bestseller since "Abnegation.

A heated war began between M. Wickramasinghe, who sought to add philosophical insight to the Jataka story and Russian literature and find a way to revitalize contemporary Sinhala literature, and E. R. Saratchandra, who sought to improve the quality of Sinhala literature by applying the theories of L. A. Richard's literary criticism.

As a result, a rift arose between the Colombo School (composed of writers and poets who generally emulated Western literature, especially 19th century English Romantic literature, but who also emphasized traditional four-line poetry and adhered to classical literature) and the Pheradeniya School (the current name of the University of Sri Lanka) (composed of university professors who took a radical stance, advocated freedom of thought, and engaged in creative fiction and free verse, as well as contemporary Sinhala theater), which was centered on the former. The latter group consisted of university professors who took a radical stance, advocated freedom of thought, and engaged in creative fiction, free verse, and contemporary Sinhala theater.

From the Pereradeniya school, Siri Gnassinha paved a new path by writing the novel "Shadows" (1960), which depicted various aspects of the people by adding free verse and plain vocabulary, completely free of formality, as opposed to the ancient tradition of rhyming verse consisting of four lines per verse.

Gunadasa Amarasekhara, another professor, actively ingested Western thinking with a Sinhalese idiom appropriate to modern terms and a lyrical style. In his collection of short stories "The Red Rose" (1952), his approach is in keeping with the artistic resignation of Chekhov, who said, "It is enough to write faithfully and sincerely as you see and feel. In addition, "The Bicycle" in the same work was inspired by the Russian writer Nikolai Gogol, who laid the foundation of humanism.The Mantle.and a living copy, reflecting the author's concern for the downtrodden of Sri Lankan society and his indignation and protest against society. In "The Kaoru of Life," published in 1956, he returned to his original literary point of view and sharply depicted the contact between life and death.

A book, "Sinhala Novels and the Shadow of Japanese Genre Fiction" (1969), which could be interpreted as a letter of challenge to the Peradeniya school, was published by M. Wickramasinghe, a leader of the Colombo school. Both works were modeled after Osamu Dazai's "Shayo" and "Ningen Shikkaku," and Yukio Mishima's "The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. These works, which were no longer suppressed due to the defeat in World War II, resulted in the creation of the arbitrary "Shayo" tribe, and were considered to be genre novels set against the backdrop of the confused Japanese society that accompanied the social upheaval of the war.

He also pointed out that E. R. Saratchandra's "The Deceased" was greatly influenced by Kawabata Yasunari's "Snow Country" and "Thousand Cranes," and the conflict between the two factions escalated into ugly personal attacks through lectures, newspapers and magazines, and eventually threatened to split the Pehradeyan sect as well.

Nan'un-do, Edirivila Saratchandra, translated by Tadashi Noguchi, The Deceased, p374-376

Indeed, Saratchandra's "The Deceased" and "The Day of Death" are clearly different in style from Wickramasinghe's work.

Wickramasinha's, which we have previously featured on our blog.The Path of the LotusWhen I read Saratchandra's "The Deceased," I couldn't help but murmur, "Ah... literature..." But when I read Saratchandra's "The Deceased," I couldn't help but think, "Oh, this is a novel.

What constitutes "literature" and what constitutes a "novel" may be defined differently for each person.

But I have read both of these works and frankly felt that way.

It is true that Wickramasinghe's works are influenced by Dostoevsky, so they are weighty and thought-provoking.

In contrast, the story of "The Deceased" moves along surprisingly lightly. It is extremely easy to read. In other words, it has the atmosphere of a modern entertainment novel. The atmosphere is almost the same as that of contemporary novels that we usually read with ease.

Of course, that does not mean that this work is not superior to Wickramasinha. The debate over whether entertainment fiction is superior or inferior to ideological fiction is a moot point here.

Also, while the first part, "The Deceased," is told from the perspective of a Sri Lankan painter, the second part, "The Day of Her Death," tells the story from Noriko's "I" narrative during the same period. The differences between the two people in love are beautifully brought out by the difference in perspectives in the first and second parts of the story. Was this elaborate narrative technique one of the specialties of the Pereradeniya school? I am curious about that too.

What surprised me when I read this commentary was the extent to which the works of Japanese authors had influenced Sri Lanka. I wondered if Japanese literature of that era had a unique brilliance. I felt a renewed sense of duty to read Japanese literature.

Finally, the commentary above mentioned that the conflict between these two great writers escalated too much, which I find unfortunate. And it seems that this conflict has cast a shadow not only over the relationship between the two, but also over Sri Lankan literature as a whole. Let's continue to look at it.

From the 1940s to the early 1970s, Sinhala literature was supported by a limited readership consisting of Sinhala-educated middle-class youth, teachers, monks, urbanites (workers, lower-class bureaucrats, etc.), and village elites, and on this basis it enjoyed what might be called a revival of medieval literature. On the other hand, not as much attention was paid to improving the quality of young writers and small writers as had been claimed. The Sinhala literature, on the other hand, has not paid as much attention as it should have to the improvement of the quality of young writers and small writers, thus protecting a somewhat isolated world and blocking the way to open up new horizons in literature.

The negative effects of the two factions' warfare lingered long afterward, causing a kind of frustration not only among writers, but also among the reading public. There were many other factors as well. During this period, the rise of popular culture, including movies, radio, music, theater, and, more recently, television, pushed print culture further to the margins.

The publishing industry, which relied heavily on imports for printing paper, petitioned the government to impose tariffs amounting to 251 TP3T, while at the same time aggressively introducing state-of-the-art printing presses and reducing the number of employees. However, the unit price of books increased several-fold, and even among the masses and ardent lovers of literature, hit by the country's chronic economic recession and protracted ethnic strife, the availability of books declined sharply. The phenomenon of the disappearance of more and more books from library collections may be a true testament to one aspect of their suffering today. Major publishers are busy with stable orders for textbook printing and only occasionally reprinting out-of-print novels, while many small writers continue their literary activities by bowing to small and medium-sized publishers. The contemporary Sinhala literary scene is on the verge of death.

Opportunities to read literary works are as nonexistent today as they have ever been. If the translation of literary works by bilingual elite writers and English-language intellectuals (whose English skills are now severely limited to the mature generation) were promoted, the number of readers and researchers would increase both inside and outside of Japan, not to mention the number of people who read and study literature. Unfortunately, however, there is no sign of such a movement, and the trend of intellectuals going abroad to work as laborers continues unabated, and I even feel a sense of worry that the current situation will wither away.

Nan'un-do, Edirivila Saratchandra, translated by Tadashi Noguchi, The Deceased, p376-377

Knowing the situation of publishing in Sri Lanka, it may seem that Japan's publishing industry is an anomaly. In Japan, books are being sold one after another in large quantities. It has been a long time since the publishing industry was in a recession, but when I think about the situation in Sri Lanka, I realize how blessed we are in Japan. (On the other hand, there may be some adverse effects such as too much competition and too many ups and downs...)

There is so much to think about Japan through Sri Lankan literature.

This book, "The Deceased," is exactly the same.

How did the Sri Lankan painter see Japan? How did he feel about Japanese spirituality?

I also wondered how the author, Saratchandra, was able to describe in such detail the mind of a Japanese woman, the unique mental climate of Japan, and the work environment. It was so realistic that it was almost painful for me. If I were to visit Sri Lanka, I am not at all confident that I would be able to observe the society in such detail. I can only take my hat off to Saratchandra for his observation and insight.

However, in terms of preference of works, I prefer Wickramasinha. This is probably because I love Dostoevsky so much.

It was very meaningful for me to be able to taste the works of two of Sri Lanka's greatest artists in this way.

After all, there are things you can't see in academic or reference books that you can feel only in novels. It was a very stimulating read. I am finally looking forward to going to Sri Lanka.

I highly recommend this work to everyone.

The above is a summary of "E. Saratchandra's "The Deceased" - Comparable to that Oshin! A novel diptych set in Japan that became immensely popular in Sri Lanka!" The above is the summary of "The Deceased" by E. Saratchandra.

Next Article.

Click here to read the previous article.

Related Articles