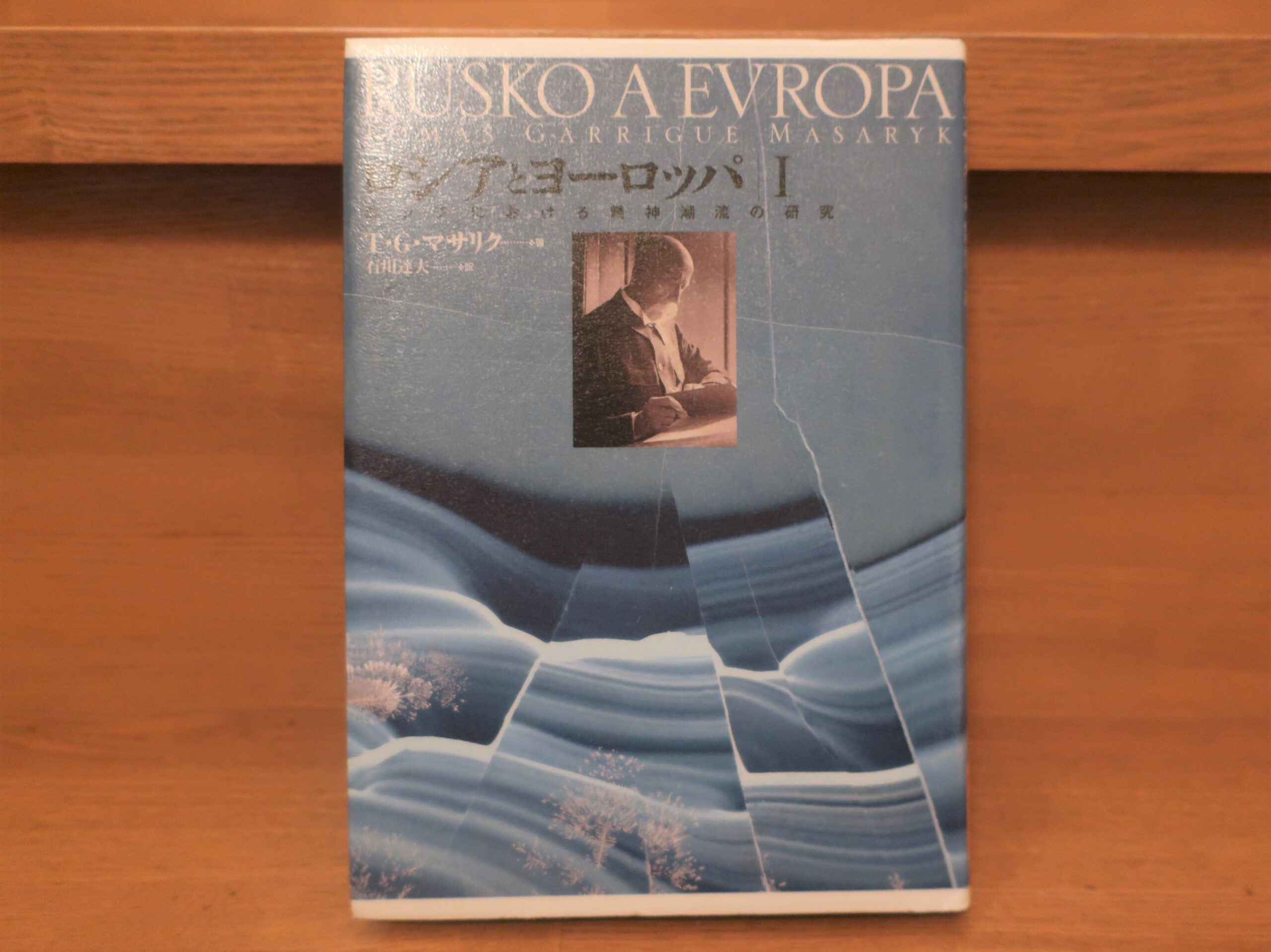

T.G. Masaryk, "Russia and Europe I," a valuable discussion of Russia by the philosophical president of the Czech Republic!

Introduced here is "Russia and Europe I: A Study of Spiritual Currents in Russia," written by T.G. Masaryk and translated by Tatsuo Ishikawa, published by Seibunsha in 2002.

Let's take a quick look at the book.

Czech thinker T. G. Masaryk (1850-1937) was also a renowned Russian researcher, and this book is the culmination of his Russian studies. This work is known as a classic in the study of Russian spiritual history, and has been translated into various languages, with the first two volumes published in Japanese by Misuzu Shobo under the title "Roshia Shiso Shishi" (History of Russian Ideology) (currently out of print). This Japanese translation is based on the Czech edition (1995-6), which was published after rigorous revision by the Masaryk Institute in Prague, and includes the third volume, which has not yet been translated into Japanese.

Part 1, "Various Issues in Russian Philosophy of History and Religion," provides an overview of Russian history from the origins of the Russian state to the First Revolution as a prerequisite for understanding the Russian spirit. Part 2, "Outline of Russian Philosophy of History and Philosophy of Religion," examines thinkers from Chaadayev to Gertsen.

Seibunshahome page.

This book was previously introducedConversations with Masaryk: The Life and Thought of a Philosopher President."This is a Russian theory by Masaryk, the philosophical president of the Czech Republic, which also appeared in the article

We have talked about Masaryk in this article and will do so again here.

Tomáš (Garrigues) Masaryk (1850-1937) was a great Czech-born thinker and politician. He was born to a Slovak serf father and a Czech cook mother in rural Moravia, a region of the Czech Republic that had been a Habsburg possession since the Czechs were deprived of their independence in the early 17th century.

After studying philosophy at the University of Vienna, where he earned a doctorate in philosophy and a professorship, he taught at the University of Vienna and the University of Prague, among others, while deeply investigating Czech historical philosophy in particular. At the same time, he energetically engaged in political, social, and cultural activities aimed at the realization of these ideals, eventually leading the Czech nation to spiritual and political independence.

After the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic, he was called the "Liberator" and "Father of the Fatherland," and earned the immense respect of his people. (he declined the nomination).

Masaryk's Czechoslovakia was perhaps one of the best and highest democracies that ever existed, although between the two World Wars the (First) Republic of Ciechoslovakia became one of the most industrialized countries in the world and above all a highly democratic and cultural state" - (Karl Popper ) Such a development was due in no small part to Masaryk's long efforts before and after the war.

Some line breaks have been made.Seibunsha, Karel Chapek, translated by Tatsuo Ishikawa, Dialogue with Masaryk: The Life and Thought of the Philosopher President, p. 329.

It's a unique career to go from philosopher to president.

Masaryk actually wrote this book in order to research Dostoevsky. In the preface to the book, Masaryk writes

This study seeks to capture the inner life of Russia from its literature. In particular, I have long studied Dostoevsky and his analysis of Russia. And, as such, the Dostoevsky part of this study will be the main part.

In the first place, this entire work is for Dostoevsky alone, but I cannot construct the text so skillfully that I can properly and adequately incorporate everything into my account of Dostoevsky. Hence, I have divided this work into parts. The first part summarizes the doctrines of Dostoevsky's predecessors and successors in the philosophy of history and philosophy of religion, and provides an outline of the history of the development of their various ideas.

Since I will refer to this and that historical phenomenon at the individual authors, I have chosen to provide an introduction to Russian history in advance. In order not to complicate the explanation with notes and digressions, I have rather presented a systematic overview of historical developments, which at the same time is a preview of the various issues that will be dealt with later.

The first half of Part II (Volume 3) deals with Dostoevsky's philosophy of history and philosophy of religion (The Struggle for God - F. M. Dostoevsky and Nihilism), while the second half includes an attempt to clarify the relationship between Russian and European literature since Pushkin and Dostoevsky (Giants. Principle or Humanism? From Pushkin to Gorky).

This work itself will show that I was right in choosing Dostoevsky's analysis for my Russian studies, but this point may be doubted from the beginning. Several experts have communicated this doubt to me (verbally) in advance: ....... But I think I can show that I was right in choosing Dostoevsky. Despite, or precisely because of, my own complete rejection of Dostoevsky's view of the world and life.

Seibunsha, Dialogue with Masaryk: The Life and Thought of the Philosopher President, translated by Karel Čapek and Tatsuo Ishikawa.P8

The book shows the magnitude of Dostoevsky's presence for Masaryk.

Russia and Europe" is a three-volume book, and Volumes I and II focus mainly on the history of Russia and the history of Russian thought. The third volume finally gets into the main subject, Dostoevsky.

In this first volume, "Russia and Europe I," Masaryk's view of Russia is discussed in considerable detail, which is quite interesting.

As you can see at the end of the above postscript, Masaryk takes a critical look at Russia and Dostoevsky. He analyzes Russian history and thought very calmly from the standpoint of a Western European philosopher and intellectual.

Scientific man no longer believes in revelation and generally has no faith. They skepticize, criticize, and strive for certainty, and counterbalance their grounded and motivated beliefs with blind faith and trust. It is critical thinking, not authority and tradition, that determines what is true. Hence, let us say this again. Kant's criticalism therefore has world-historical significance, and criticalism implies the full awareness of modern man of the world and society. (omitted).

Today, the religious question is as follows. Namely, is it possible to have a non-enlightened religion? Can a scientific, critically thinking human being, a philosopher, have a religion, and what kind of religion?

Seibunsha, Dialogue with Masaryk: The Life and Thought of the Philosopher President, translated by Karel Čapek and Tatsuo Ishikawa.p

161

Masaryk goes on to describe the reception and role of Russian Orthodoxy in Russian history as superstitious.

This is "Russia as Asia" as seen from the European side, the Eastern Church as seen by Catholic and Protestant Christians, and religion as seen by philosophers and scientists.

Of course, Masaryk is not dismissing Russia or the Russian Orthodox Church out of hand. It is only a question of what would happen if we were to look at Russia thoroughly and critically from the standpoint of a philosopher and a Westerner, and that is what we will find out in this book.

It was very interesting to see how the most respected Czech philosopher president of the time viewed Russia.

To begin with, he is a top-notch philosopher. Masaryk was also a politician with experience in world affairs, politics, and economics. He was also a great personality who was respected not only by the Czech people but also by people all over the world.

The Russian history and Dostoevsky theory told by such a person was extremely stimulating.

This book, "Russia and Europe I," provides an insight into Russian history and Masaryk's ideological position. Of course, the book was written at the end of the 19th century, so its historical accuracy may be less than current research. However, it is the best book to learn how the leading European intellectuals of the time viewed Russia.

I also recommend this book.

The above is "T.G. Masaryk's "Russia and Europe I," a valuable Russian theory by the philosopher president of the Czech Republic! was.

Click here to read the previous article.

Related Articles