Robert Hooke's "Micrographia" Overview and Comments - An amazing catalogue work by the natural scientist who was the first in the world to discover cork cells under a microscope.

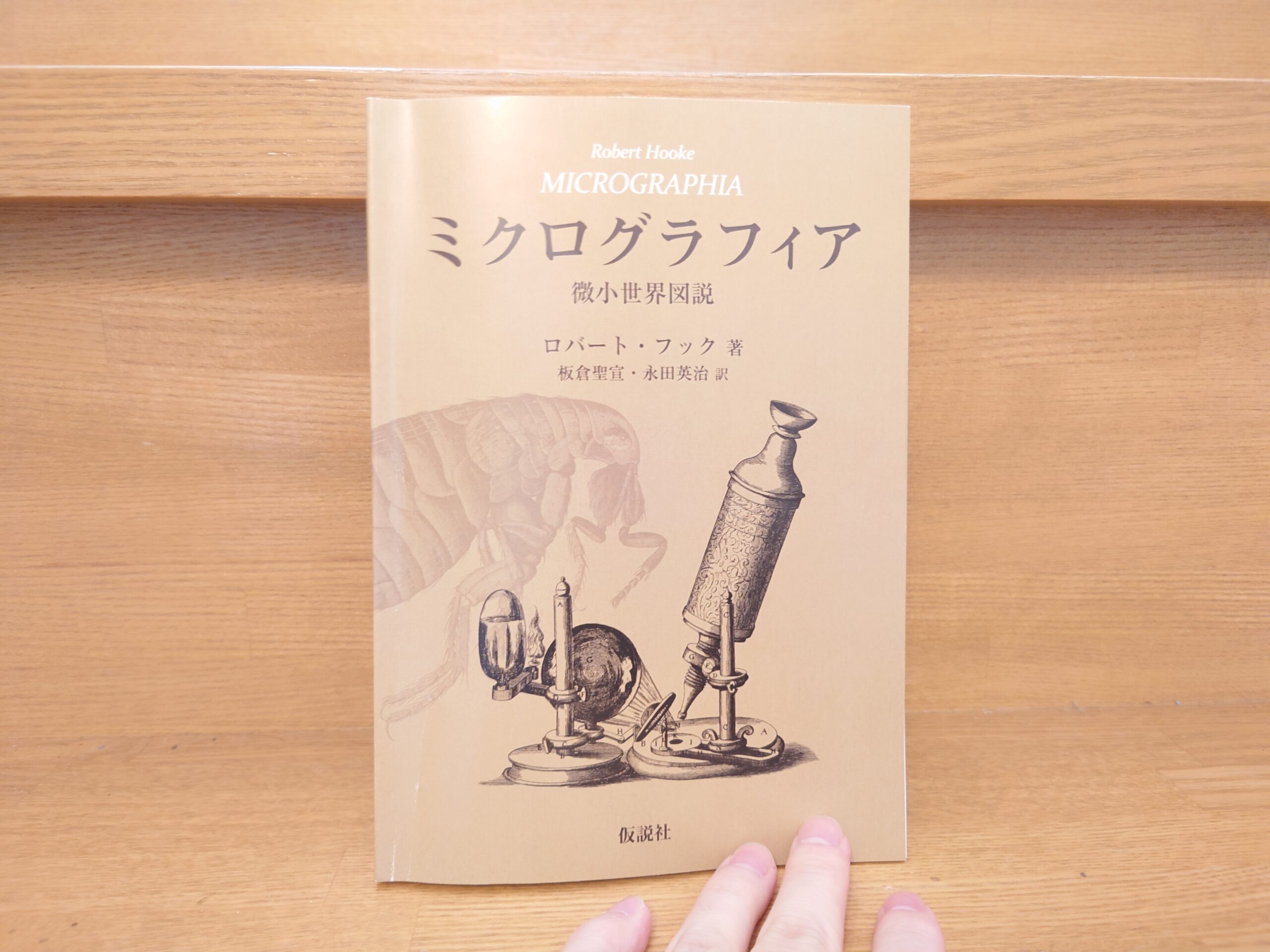

I would like to introduce "Micrographia" published by Robert Hooke in 1665. I have read the 2013 on-demand edition of Micrographia, translated by Seinobu Itakura and Eiji Nagata, published by Hypotheses, Inc.

The book's author, Robert Hooke (1635-1703), was an English natural scientist and a key figure in the Royal Society of England. Unfortunately, no portrait of him survives. (It is not known exactly why, but some say it was because of a bitter dispute with Newton.)

Robert Hooke is famous for being the first person in the world to discover "cells" by observing cork under a microscope.

I introduced Robert Hooke's writings in my previous articlePaul de Klyffe, "The Microbe Hunter" - "The extraordinary life of Löwenhoek, famous for his microscope and microorganisms: the discovery and impact of the invisible world."This was because of the strong connection with Löwenhoek, which I discussed in

Löwenhoek was an official in the Dutch town of Delft, but he was self-taught and built his own microscope, which he continued to improve and observe steadily for more than 20 years, and as a result discovered microorganisms in water.

If he had died without being known to the world, the history of the world might have been very different from what it is today.

It was the Royal Society and its leading figure, Robert Hooke, who brought him to prominence.

Robert Hooke was also a man who explored the world invisible to the naked eye with a microscope. I picked up this book because I wanted to read Hooke's book to learn about the worlds explored by both Lehwenhoek and Robert Hooke.

Let's take a look at the content of this work and the process of its formation.

The following quote is by Laura J. SnyderVermeer and the Scientific Genius: The Revolution of "Light and Vision" in Seventeenth-Century Holland."The book is called. This book is a classic book that examines two explorers of light, Vermeer and Löwenhoek, in the context of their times. The explanations in the book are very easy to understand, so I will introduce some of them here. It is a bit long, but it is an important part of the book, so I will read it carefully.

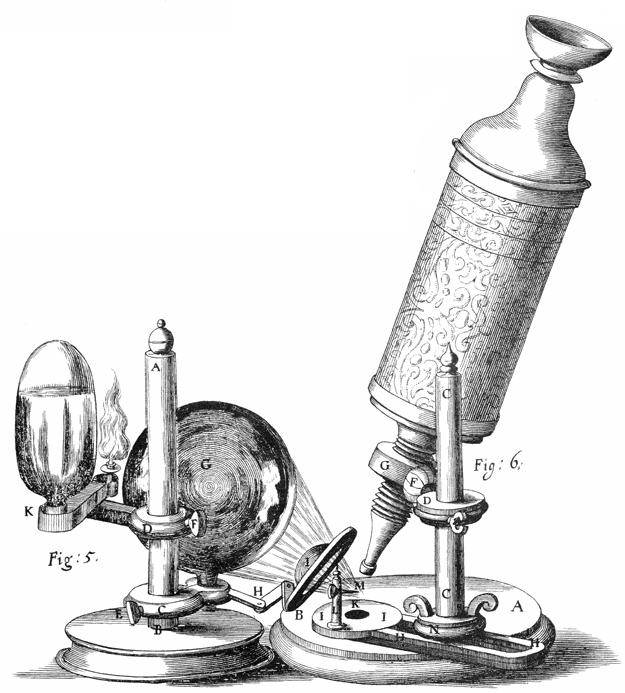

In 1663, the Royal Society ordered Hooke to conduct a detailed observational study with a microscope. On March 25, Hooke demonstrated his microscopic observations in front of the Fellows (he had previously shown them snow and frozen urine crystals). He demonstrated it again at a meeting the following week. On April 8, he "delighted" the Fellows by showing them ordinary moss under the microscope.

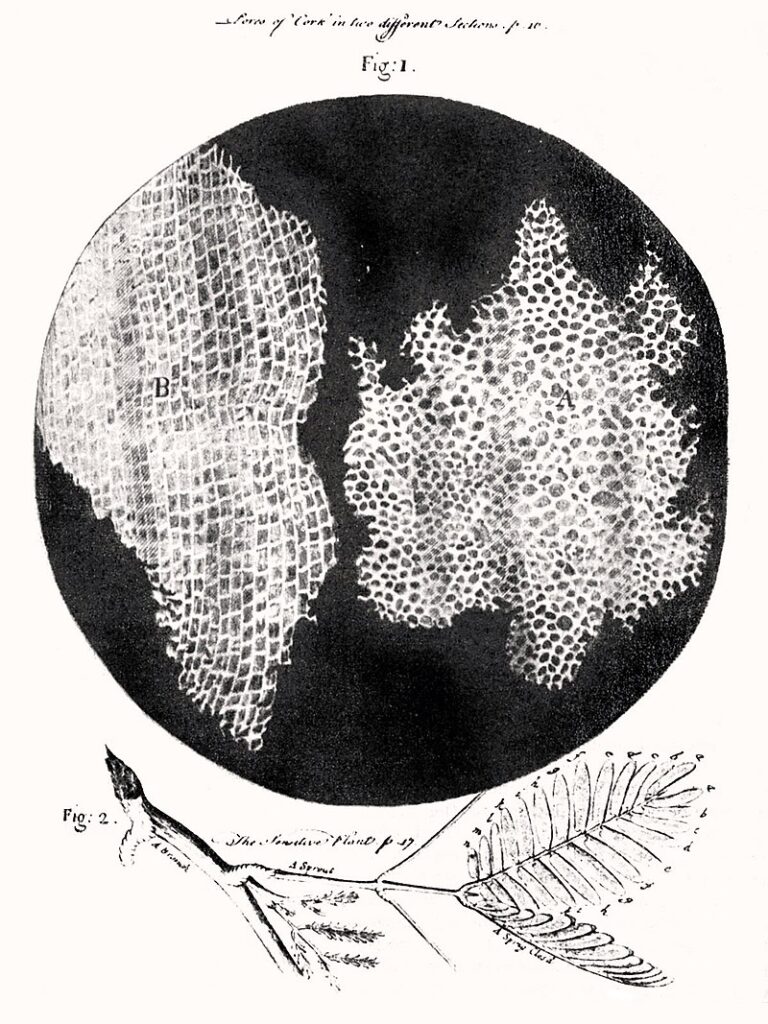

The following week, a thin slice of cork, both longitudinally and horizontally, was shown under a microscope. The microscope revealed that the cork was made up of numerous spaces solidified in the wall. Hooke recalls what he saw at that time.

With a sharp knife, I cut a very thin sliver from the smooth surface of the cork. Since the flake itself was white, I placed it on a black speculum and shone light on it through a thick plano-convex lens. Thus, I could see with surprising clarity that "the cork flake is porous, with its entire surface penetrated like a beehive. However, the pores are not arranged in a regular pattern like a beehive. ...... These pores, i.e.small roomis made up of "so many little boxes that are not very deep and are separated by ...... several diaphragms". (Micrographia: An Illustration of the Microscopic World, above)

No one had ever confirmed that there were such innumerable spaces within the cork, and no one had ever imagined that such a thing existed. Hooke called this box-like pore "the cork," because of its resemblance to the small rooms where monks sleep.priests' temple quartersThe hook was named "Hook" in Japanese. Thanks to the meticulous thinning of the cork, the hooks werecell (biology)The discovery of the "brick" that makes up all living things, the "brick" that is the "brick" that makes up all living things.

For the next five power months, the Fellows of the Royal Society peered into the microscope again and again at their weekly meetings, enthralled by the sights they could see through the lens. Hooke used the microscope to take the Fellows into a world invisible to the naked eye. (omitted).

These random demonstrations of microscopic observation continued until September of that year. The most outstanding of these demonstrations was one Hooke gave in July before King Charles II. Charles II was a patron of the Society and a considerable supporter. After the demonstration, the compilation of observation records began immediately. It was published as "Micrographia" at the beginning of 1665.

The publication of Micrographia was a scientific and literary coup. When Samuel Peeps saw "Micrographia" being bound at his favorite bookbinder's, he ordered it on the spot. He read it until late at night the same day he got it, and declared it "the most original book I have ever read.

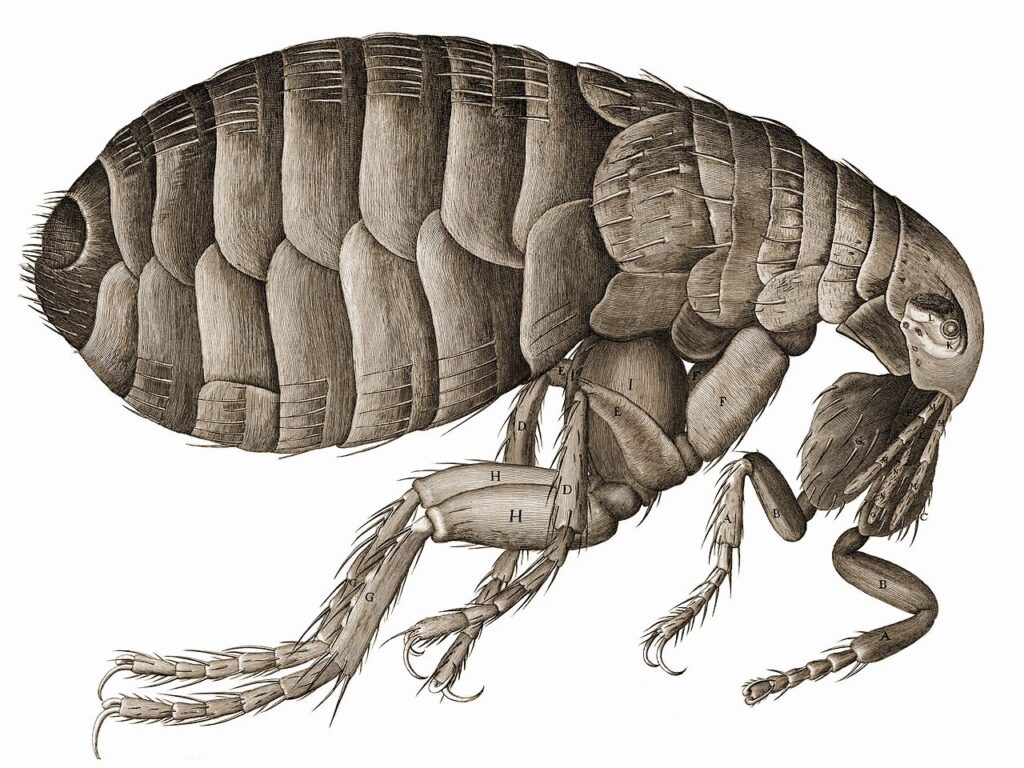

It was no wonder that Peeps was so excited. Micrographia is the first research paper to devote (almost) all of its text to microscopic observations. A total of 60 observations are listed, of which five are of man-made objects (fabrics, razor blades, etc.), five are of inorganic objects (sand, ice crystals, etc.), 15 are of plants (corks, sponges, etc.), and 27 are of animals (mostly insects). The remaining eight are non-microscopic observations of light, stars, the moon, etc. (omitted).

The natural philosophers and the general readership of Micrographia were astonished by the numerous illustrations in the book. Among them was an illustration of a flea the size of a cat, so large that it could only fit on a fold-out page, which even Christopher Huygens, who despised Hooke, found astonishing.

His friend Christopher Wren may have assisted him in making such etchings, but even so, they are all based on Hooke's own drawings. We can glimpse a glimpse of his talent, which he had studied as a boy as a pupil of the court painter Peter Lely.

The copperplate engravings, which cover a total of 28 pages, show incredibly detailed depictions of even the tiniest details that can only be seen with the aid of a microscope, a new and innovative instrument.

Hook's illustrations silently appeal to the viewer's mind. God has given beauty and complexity to even the smallest and lowest of creatures. And above all, that this invisible world can be observed with the aid of a microscope.

Hara Shobo, Laura J. Snyder, translated by Akito KurokiVermeer and the Scientific Genius: The Revolution of "Light and Vision" in Seventeenth-Century Holland."P265-269

Some line breaks have been made.

These are the episodes of the famous observation of the cork and the discovery of the cell. It was this discovery that led to the writing of "Micrographia" under the auspices of King Charles II.

As mentioned in the quote above, Hooke depicted the objects of his observation with astonishing precision. The book "Micrographia" is a collection of his drawings.

No one could have imagined that there was such a complex and mysterious structure in the world invisible to the naked eye. His discoveries may truly be compared to those of Copernicus and Galileo.

And I have a feeling that this book will help me.

That is, "Robert Hook cares tremendously about the church.

I stated just a few moments ago that his discoveries may be comparable to those of Copernicus and Galileo.

They observed the celestial bodies and stated that a different world from the biblical one is real.

But what happened to them after that?

Yes, they are. They will be subjected to the Inquisition by the Church.

Scientific thinking can destroy the Christian worldview and order.

The fact that it contradicted what the Bible says was a very vexing issue for the Catholic Church.

Robert Hooke was a scientist who worked in England.

If this had been in Spain, Italy, France, or Austria, where Catholicism is strong, they would have been subjected to the Inquisition or put in a very difficult position in social life.

England and the Netherlands were Protestant, separated from Catholicism. I can't talk about it here because it would be too long, but the main reason why Hooke and Löwenhoek were able to be active was because they were Protestant countries.

At the same time, they are alsoHe used a microscope to "learn more about God's work."It is also important to take the attitude that Science was not pursued to rebel against the teachings of the Church, but precisely as a means to explore God's world more deeply.

These ideas were originally deeply rooted in regions such as Holland and Belgium, and became the basis for the birth of unique landscape paintings by Bruegel and others. I think it is very important to note that Northern Europe had its own unique culture that was different from that of Southern Europe, such as Italy and Spain. Please refer to the following article for more information on this topic.

Robert Hooke, in the preface to his book "Micrographia," writes, "I would like to introduce to you a passage that makes it very easy to understand how he cared about the church. I would like to introduce here a passage that makes it very easy to understand how he cared about the church.

When it comes to the acuteness of the senses, other creatures are in many ways far superior to humans. It is hard not to admit that the human senses are far from perfect. These defects of the senses are based on two reasons. One is that the objects are beyond the capacity of the sense organs. That is, a myriad of things are beyond the capacity of the sense organs. The other is due to errors of perception. In this case, the objects that enter the sense organs are not received correctly.

A similar defect is found in memory. We often forget many things that we should remember, and most of what we remember is either insignificant or incorrect. And even if our memories are secure and important, they are forgotten over time. And eventually, we are overwhelmed by more trivial thoughts and buried under them, so that when we need them, we can't remember them.

The two foundations of perception - sensation and memory - are easy to fool us. So the work we do based on them-arguments, conclusions, definitions, judgments, and all other kinds of reasonwork (i.e. performance, words, actions, etc.)(REASON) One can easily have the same defects, and it is not surprising if they are futile or uncertain. Therefore, the fault of understanding lies in the senses and in memory, and defects arise in both the quantity and the quality of knowledge. The reason is that the scope of our thinking is small compared to the vast expanse of nature itself. That is, some parts of nature are too large to understand, and some are too small to perceive.

Therefore, if we do not have a thorough perception of an object, our conception of it and all the arguments we make based on it must be completely incomplete and muddled. We often see shadows of things and mistake them for matter, we mistake matter for something that looks a little like it, and we mistake analogies for definitions. And even many of the things we consider to be the most reliable definitions turn out to be merely expressions of our own misapprehensions, rather than the essence of the thing itself.

The consequences of these imperfections manifest themselves differently, depending on one's temperament and disposition. Some people are prone to extreme ignorance, while others are boldly dogmatic without any guarantees and unreservedly impose their opinions on others.

Thus, any uncertainty or error in human conduct is (1) based on the narrowness and uncertainty of our senses, (2) due to the uncertainty or misconception of our memory, and (3) due to the limitations and thoughtlessness of our understanding. Therefore, it is not surprising that "our ability to improve our understanding of the causal laws of nature is slow and sluggish. Not only must we consider the ambiguity of our own efforts to work and think, but we can also see that "even our own mental faculties can bruise themselves.

The process of human reason involves such dangers, but the way to overcome them can only come from a true mechanistic experimental philosophy [of natural science]. It is precisely in this respect that the experimental philosophy has an advantage over the philosophy of reason and argument, a philosophy that aims primarily at the skillful use of deductions and conclusions, with little regard for the underlying principles that are supposed to be based on sense and memory, and that correctly sequences the deductions and conclusions so that they are mutually useful. It has an advantage over philosophies that correctly order their deductions and conclusions and make them mutually useful.

Hypothesis-sha, Robert Hook, Seinobu Itakura, translated by Eiji Nagata, Micrographia Micro World Illustrated, 2013 on-demand edition, p. 6-8

I know this is a bit long, but what do you think? I think it is rare to find an introduction that so carefully defends its own position.

The hook is not that God or the Church is wrong, but only thatPeople are flawed."I will discuss my own theory from the standpoint that With the fear of the Inquisition, what more skillful defense could there be?

And not only that, but I thought it was a good thing that he cleverly added a tinge of irony to the Catholic fanaticism of the Inquisition in the process. Above,The consequences of these imperfections manifest themselves in different ways, depending on one's temperament and nature. That is, some people are prone to extreme ignorance, while others are boldly dogmatic without any guarantees, or unreservedly impose [their] opinions on others."It seemed to me that the very phrase, "I am not a Catholic," was an ironic reference to the Catholic Inquisition.

I imagine that some of these criticisms of Catholicism would have been more readily accepted in Protestant countries.

And Hook will continue with these arguments carefully and meticulously from here on out. I would like to introduce all of them, but the volume of the article does not allow me to do so.

But I would like to take up one last word from Hook. Here it is.

In general, human beings prefer the plausible and obscure parts of learning rather than the true and solid parts.

Hypothesis-sha, Robert Hook, Seinobu Itakura, translated by Eiji Nagata, Micrographia Micro World Illustrated, 2013 on-demand edition, p. 46.

These are words that resonate strongly with those of us living today.

We are the ones who must now take these words of warning seriously.

Science is so advanced today, why should we be fooled by such superstitions?"

Some may think so.

But that carelessness is dangerous.

So far in this blog, we have discussed the "dangers of information in our time" from various angles.

We humans have basically not changed for thousands of years. I believe that it is a complete illusion to say that we are progressing. I believe that while there have been advances in knowledge and technology, the essence of human nature has not changed at all.

Throughout this work, Hooke explains the flaws in human cognition and thinking and describes the importance of scientific thinking. We live in a modern age of scientific development, but do we really think scientifically every day?

Are you convinced that what you are told or advertised is the truth? Are we not being driven by our emotions?

If so, it would be exactly the same as Hooke saying that he prefers the plausible and trivial parts.

It seems very significant that Robert Hooke has been warning us about this for more than 350 years. I felt strongly that I must also be very careful.

As a religious person, I was interested in this aspect of the book, but it is also a very good catalog of works. I have already mentioned Hooke's drawings of fleas, but there are many more in the book, and I am simply amazed at the precision of his observations more than 350 years ago.

I think this book is a very good work, stimulating from many different directions. I picked up this book because of my connection with Löwenhoek, and I found it a very meaningful read.

The above is "Robert Hooke, 'Micrographia,' the amazing catalogue work of the natural scientist who was the first in the world to discover cork cells under a microscope.

*The product link below is for the larger Amazon version, but I purchased the on-demand version from Rakuten. It is smaller but more inexpensive.

Next Article.

Click here to read the previous article.

Related Articles