Takeaki Enomoto's "Siberian Diary" Summary and Impressions - The great man associated with Hakodate had crossed Russia and Siberia!

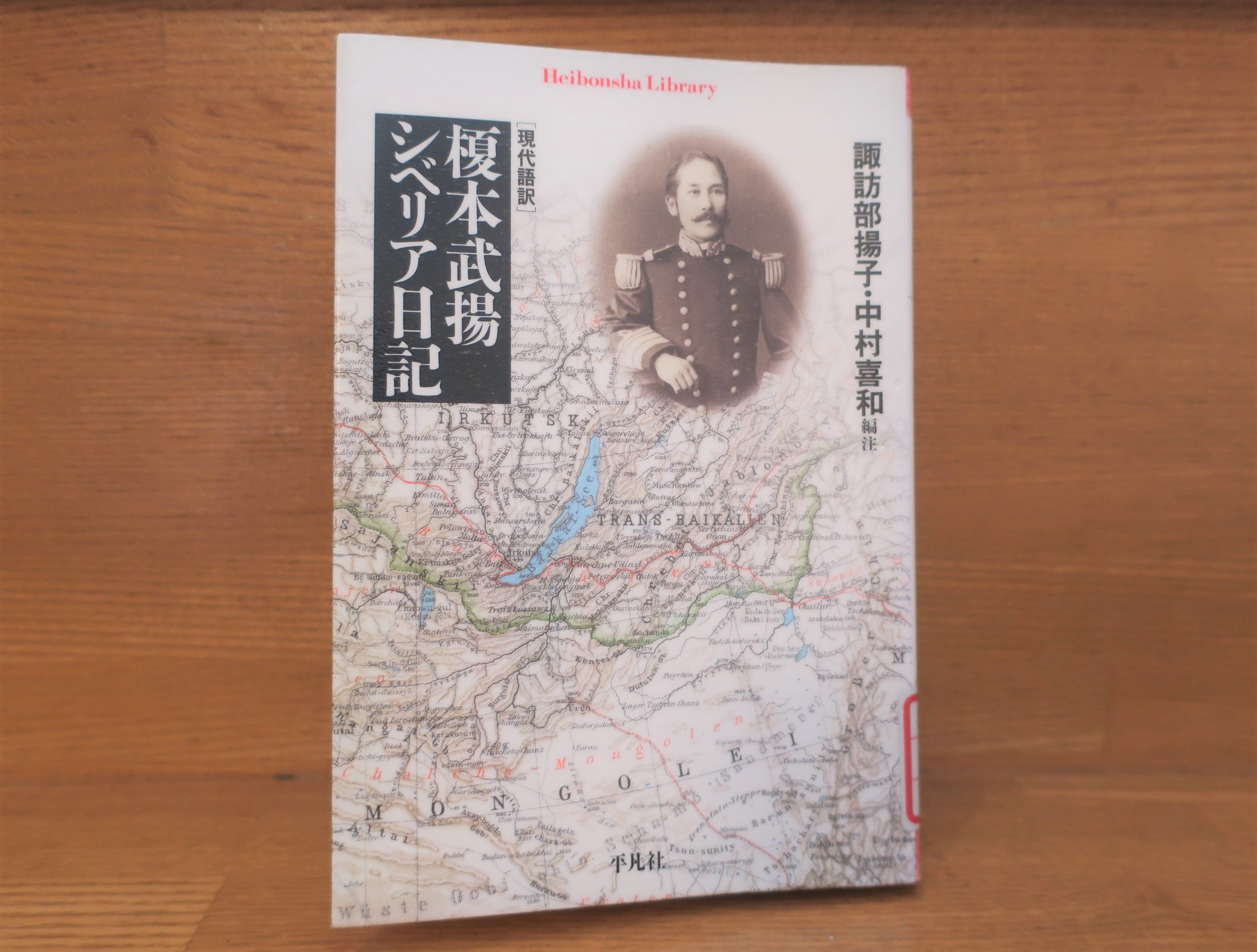

The book I read, "Siberian Diary," written by Takeaki Enomoto and edited and annotated by Yohko Suwabe and Kiwa Nakamura, was published by Heibonsha in 2010.

Let's take a quick look at the book.

Defeated at the Battle of Goryokaku at the end of the Edo period, Takeaki Enomoto was later appointed by the Meiji government and went to Russia as minister plenipotentiary.

Upon his return to Japan, he chose to travel around Siberia and observed the landscape, products, industry, folk customs, transportation, and all other aspects of this northern land, with a view to the future of both Japan and Russia.

This book accompanies the journey of this rare man in a modern translation, with thoughtful notes, including the names of people and places.

AmazonProducts Page.

Takeaki Enomoto is very familiar to Hakodate residents. Goryokaku is still a symbol of Hakodate, and many people still visit the area in memory of the late Edo period warriors who fought there.

Among such aspirants, I, as a citizen of Hakodate, was surprised to discover that Takeaki Enomoto was active as a diplomat for the Meiji government after the Battle of Goryokaku, and that he even crossed Siberia from Russia and returned.

The book's foreword briefly summarizes the circumstances that led to his Trans-Siberian journey, so I will quote from that.

The Boshin War was fought from Keio 4 (the first year of Meiji) to the following year. It was a war between the old shogunate forces and the new government forces led by Satsuma and Choshu, who were under the control of the Imperial Court. The final battle took place in Hakodate (soon to be renamed Hakodate). Many people believe that Takeaki Enomoto, who commanded the old shogunate forces, disappeared from history with the conclusion of the battle at Goryokaku in Hakodate.

Enomoto was 34 years old at the time. He had not yet reached the halfway point in his life. Enomoto and other leaders of the former shogunate forces who surrendered were sent from Hakodate to Tokyo, where they spent two and a half years in prison in Tatsunokuchi (present-day Otemachi) until the New Year of 1872. There was a strong opinion that the rebel leaders should be executed immediately, but Kiyotaka Kuroda from Satsuma, who had fought against Enomoto and his men in Hakodate, made a strong appeal for their lives. Saigō Takamori and others are said to have supported Kuroda's argument.

After being released, Enomoto worked on development projects in Hokkaido with his colleagues from the spring of that year through the following year, 1873. This was because Kiyotaka Kuroda was then in charge of the Kaitakushi (Hokkaido Development Office). Enomoto had always had a strong connection with the northern lands.

Heibonsha, Enomoto Takeaki, "Siberian Diary" edited and annotated by Suwabe Yohko and Nakamura Kiwa, p. 7-8

As mentioned here, I did not know that Takeaki Enomoto was active after the Boshin War. I was surprised that he survived and played an active role in later years with the help of that Kiyotaka Kuroda and Takamori Saigo.

In 1874, Enomoto once again experienced a turning point. He was appointed minister to Russia. The post was to have gone to the noble Lord Sawa Nobuyoshi, but he died suddenly, and the position was given to Enomoto.

Heibonsha, Enomoto Takeaki, "Siberian Diary" edited and annotated by Suwabe Yohko and Nakamura Kiwa, p. 8

Takeaki Enomoto was appointed as Minister to Russia.

His main task was to negotiate a treaty with Russia. The key issues to be negotiated at this time were the territorial issues of the Northern Territories and Sakhalin, and the resolution of the Maria Luz incident, which was causing a stir in Japan and Russia at the time. He was dispatched to Russia to resolve these difficult issues.

Enomoto was sent to Russia in 1874. As an appropriate rank for a minister plenipotentiary, he was given the rank of lieutenant general of the navy. Since there were still no craftsmen in Tokyo to tailor a military uniform suitable for an admiral, he had his uniform made in Paris and arrived in St. Petersburg, the capital of the Russian Empire.

In Russia, the dispatch of the vice president of the former shogunate navy and leader of the rebel forces was seen as a rare occurrence and was greatly welcomed. Nevertheless, there was the usual haggling and negotiation that accompanies diplomatic negotiations, but in the end, the Treaty of Exchange for Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands was concluded in 1875, and the Japanese side was eventually ruled to be correct in the Maria Luz incident.

It is said that Enomoto was blessed with the qualities of a diplomat in terms of character and learning. His long period of study in the Netherlands as a young man and his familiarity with the customs of Westerners must have been helpful.

Heibonsha, Enomoto Takeaki, "Siberian Diary" edited and annotated by Suwabe Yohko and Nakamura Kiwa, p. 9

The Treaty of Exchange for Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, which we learned about in history class, was negotiated and concluded by Takeaki Enomoto!

I was also surprised to learn that he had studied in the Netherlands as a young man.

Enomoto's stay in Petersburg lasted four full years. (Enomoto's stay in Petersburg lasted four full years.)

After the Russo-Turkish War ended in victory for the Russian side, Enomoto chose to travel across Siberia when he finally returned home. Compared to the ship journey, the overland course was much more arduous.

In a letter to his wife Tatsu, he explained that the reason for this was to allay the fears of the Japanese people, who were "unnecessarily afraid of Russia and worried that it might attack Hokkaido at any moment.

It is true that Enomoto took every opportunity to inspect munitions factories and to note in his diary the deployment of troops in the cities of Siberia. But that is not all he observed.

He never forgot to pay attention to what would be useful for the development of industries in Hokkaido and Japan as a whole, and what would contribute to the promotion of trade between the two countries. He meticulously recorded the geology and agriculture of various regions of Siberia, and showed an ethnologist's interest in the customs and lifestyles of non-Russian peoples.

Because he was a man with such a broad perspective, he was able to lay the foundation for the development of modern Japan by assuming various important responsibilities in the government during the 20 years following his return to Japan in the midst of the clan system.

The distance from Petersburg, at the western end of the Russian Empire, to Vladivostok, at the eastern end, is about 10,000 kilometers, or 66 days. Counting the nights spent in different locations, we find that they spent two nights in railroad cars, 19 nights in hotels, post offices, and private residences, 20 nights in steamers, and 24 nights in horse-drawn carriages. In other words, the most nights were spent in horse-drawn carriages, which ran day and night.

Since the diary is a daily record, he must have written many of the entries while being ridden in a horse-drawn carriage. One cannot help but marvel at his mental strength.

Heibonsha, Enomoto Takeaki, "Siberian Diary" edited and annotated by Suwabe Yohko and Nakamura Kiwa, p. 9-10

Takeaki Enomoto dared to take the harsh Siberian route to broaden his knowledge of Japan to prevent the country from being swallowed up by the rest of the world. He would normally have returned to Europe by ship, but he chose the grueling Trans-Siberian route to learn more about his giant neighbor, Russia. It was a feat of extraordinary mental strength.

When you read "Siberian Diary", you will find that it is surprisingly simple and proceeds in the style of a diary. It is a diary in the style of a diary, in which the author candidly describes what he saw and how he felt on that day.

The words are translated into modern language, so it is very easy to read.

And his humor, which appears in places, makes me giggle. Particularly impressive is his struggle with bedbugs, which appear when he sleeps at night. The bedbugs seemed to be his toughest enemy during his Trans-Siberian journey, and they appear many times in his diary.

Enomoto Takeaki studied in Holland as a young man, and from there, after fighting in the Boshin War, he again traveled to Europe as a diplomat.

In this book, you can learn about the landscapes, industries, and people's lives in Siberia, which he sees for the first time.

He left Petersburg in 1878. This was Dostoevsky's last year and the year he began writing "The Brothers Karamazov". He was in Russia exactly where Dostoevsky was.

His "Siberian Diary" is an excellent source of information on the lives of Dostoevsky and his contemporaries. In this sense, I found this book extremely interesting.

The modern translation is excellent, and it is just a slick read.

It was a very gratifying opportunity to learn about Takeaki Enomoto, a great man associated with Hakodate. I am glad I came across this book.

The above is "Takeaki Enomoto's 'Siberian Diary': A Great Man Related to Hakodate Traveled Across Russia and Siberia! The above is "Takeaki Enomoto's 'Siberian Diary'.

Next Article.

Related Articles